In the rivalry for regional influence, it is not only states that jostle for strategic primacy and public positioning in Arab countries. Regional leaders have also sought to project and represent their states’ foreign policies and aspire for public recognition. Some, like Iran’s supreme leader Ali Khamenei, even have an active and multi-lingual presence on Twitter and other social media outlets to manage and promote their public image. They all appeal to transnational bonds of Arab or Islamic solidarity, as they try to justify their foreign policies within those parameters. According to Arab Barometer’s (AB) most recent data, they have not been very successful.

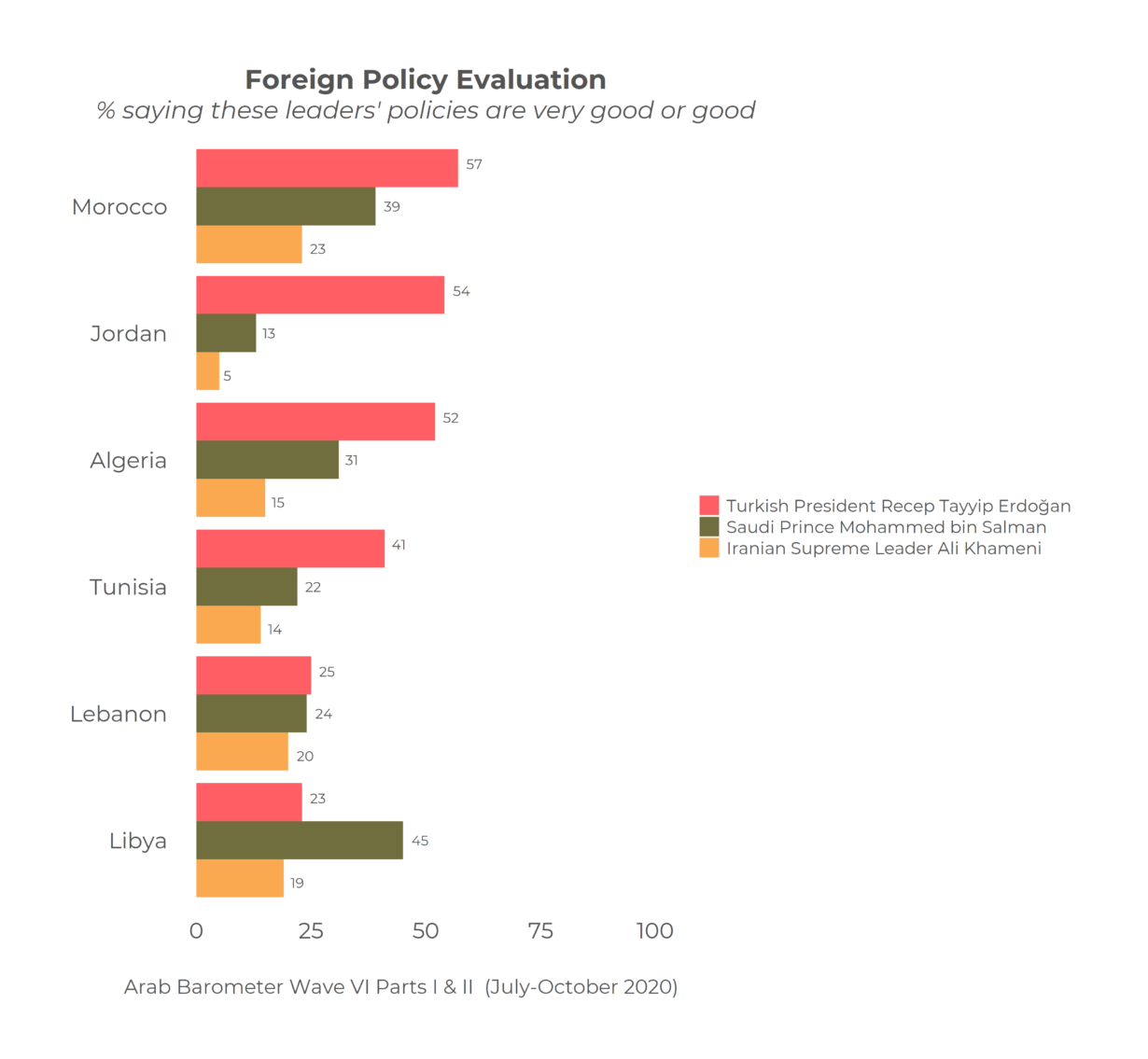

According to Arab Barometer Wave 6 data, the most popular regional leader among surveyed countries remained Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey. Asked what they thought of his foreign policies, a sizeable minority of respondents in the six surveyed countries—a little more than 4 in 10 (42 percent)—said they were very good or good. This included majorities in Morocco (57 percent), Jordan (54 percent), and Algeria (52 percent), and a sizeable minority in Tunisia (41 percent). Only in Lebanon (25 percent) and Libya (23 percent) did a smaller minority of a quarter or smaller proportion of respondents view Erdogan’s foreign policies favorably.

Less popular was Saudi Arabia’s crown prince (and de facto ruler) Mohammad Bin Salman. A small minority of respondents in the six surveyed countries—little more than 1 in 4 (28 percent)—said his foreign policies were very good or good. Bin Salman was thus significantly less popular than Erdogan in the six countries combined, and was most popular in Libya, where 45 percent looked favorably upon his foreign policies. Elsewhere, fewer proportions looked favorably upon his foreign policies in Morocco (39 percent), Algeria (31 percent), Lebanon (24 percent), Tunisia (22 percent), and Jordan (13 percent).

Finally, and despite the social media presence, Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei was the least popular among regional leaders. A smaller minority of respondents in the six surveyed countries—a little less than 1 in 6 (16 percent)—said his foreign policies were very good or good. Erdogan was thus more than two-and-a-half times as popular in the six countries combined as Khamenei, who was most popular in Morocco where 23 percent looked favorably upon his foreign policies. Elsewhere, fewer proportions thought so in Lebanon (20 percent), Libya (19 percent), Algeria (15 percent), Tunisia (14 percent), and Jordan (5 percent).

There are several explanations for why Erdogan is so much more popular in the surveyed countries than either Bin Salman or Khamanei. The first of which is that, despite his illiberal and authoritarian tendencies, Erdogan enjoys a considerable level of electoral legitimacy. Erdogan has consistently won elections that are largely free and fair, and in which voter turnout is one of the highest in the world. It goes without saying that neither Bin Salman nor Khamenei enjoy this electoral legitimacy.

A second reason may be that, under Erdogan, Turkey has become much more accessible to Arab citizens – much more so in fact than Arab countries are. In the late 2000s, the Erdogan government cancelled visas for most countries in the Middle East and North Africa – including Morocco, Tunisia, Jordan, Lebanon and (for a time) Libya – five of the six countries surveyed in AB6. Visas have been reinstated for war-torn countries such as Libya, Syria and Yemen (making it almost impossible for citizens of these countries to enter), but Turkey remains one of the few countries in the world that is open and accessible to Arab citizens. That Turkey under Erdogan has opened up to this degree towards Arab countries and citizens is reflective in the increasingly higher commercial, cultural and touristic exchange between Turkey and Arab countries. Neither Saudi Arabia nor Iran is accessible to as many Arab citizens, nor are they likely to become under their current leadership.

And then there is the transnational claim on leadership of the Muslim nation (ummah), which Erdogan makes much more effectively than Bin Salman or Khamenei. Under Erdogan, Turkey has invested heavily in cultural production geared at reviving the Ottoman imperial heritage. While this has been contested in Turkey, it has been much better received in the Arab World where there is an exacerbated and sustained leadership crisis, and where Islam’s imperial legacy is sorely missed. An elected leader of a conservative, nationalist party with Islamist roots, Erdogan claims to lead the ummah in a much broader sense than either Bin Salman or Khamenei. His own simple roots in the poor Istanbul neighborhood of Kasımpaşa perhaps lend credence to these claims. Bin Salman and Khamenei cannot make these claims with as much credibility. Afterall, Bin Salman is an heir to an absolute monarchic dynasty, whereas the clerical and sectarian dimensions prevent Khamenei from appealing to as broad of a segment of Muslims.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, there is the question of military intervention in neighboring states, which my colleague Michael Robbins addressed in an earlier post. Though all three leaders have spearheaded foreign policies that can safely be characterized as imperial, Erdogan’s has perhaps been the least costly in terms of human lives. Turkey’s ethnic cleansing of parts of Northern Syria pales in comparison to Saudi Arabia’s genocidal war in Yemen and Iran’s genocidal intervention in Syria.

As I have previously argued elsewhere, Erdogan’s popularity in the Arab and Muslim worlds is problematic. However, it is easy for the impartial observer to see why Bin Salman and Khamenei are no match.