Written and released before COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic, a 2020 Oxfam report suggested that if women were to be paid for their unpaid work, it would be worth nearly US$11 trillion globally. This sum likely varies based on the proportion of women gainfully employed in any region. At 18 percent, the 2021 rate of women’s participation in the paid labor force in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is the lowest in the world and has decreased from a 25-year high of 21 percent in 2016. Women in MENA spend up 10 times more time on unpaid care work and do 4.7 times more unpaid care work than men. But do citizens believe women should be doing so?

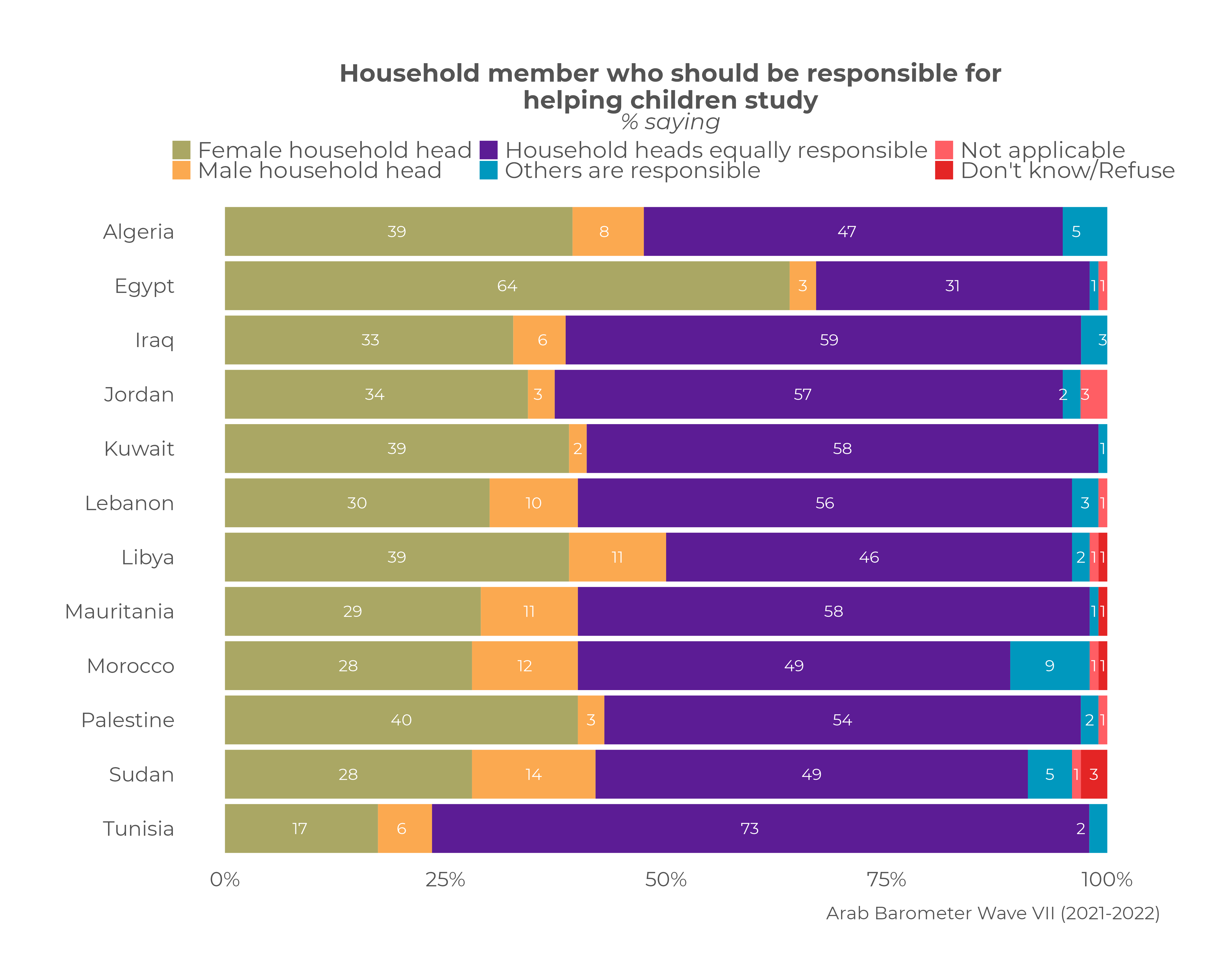

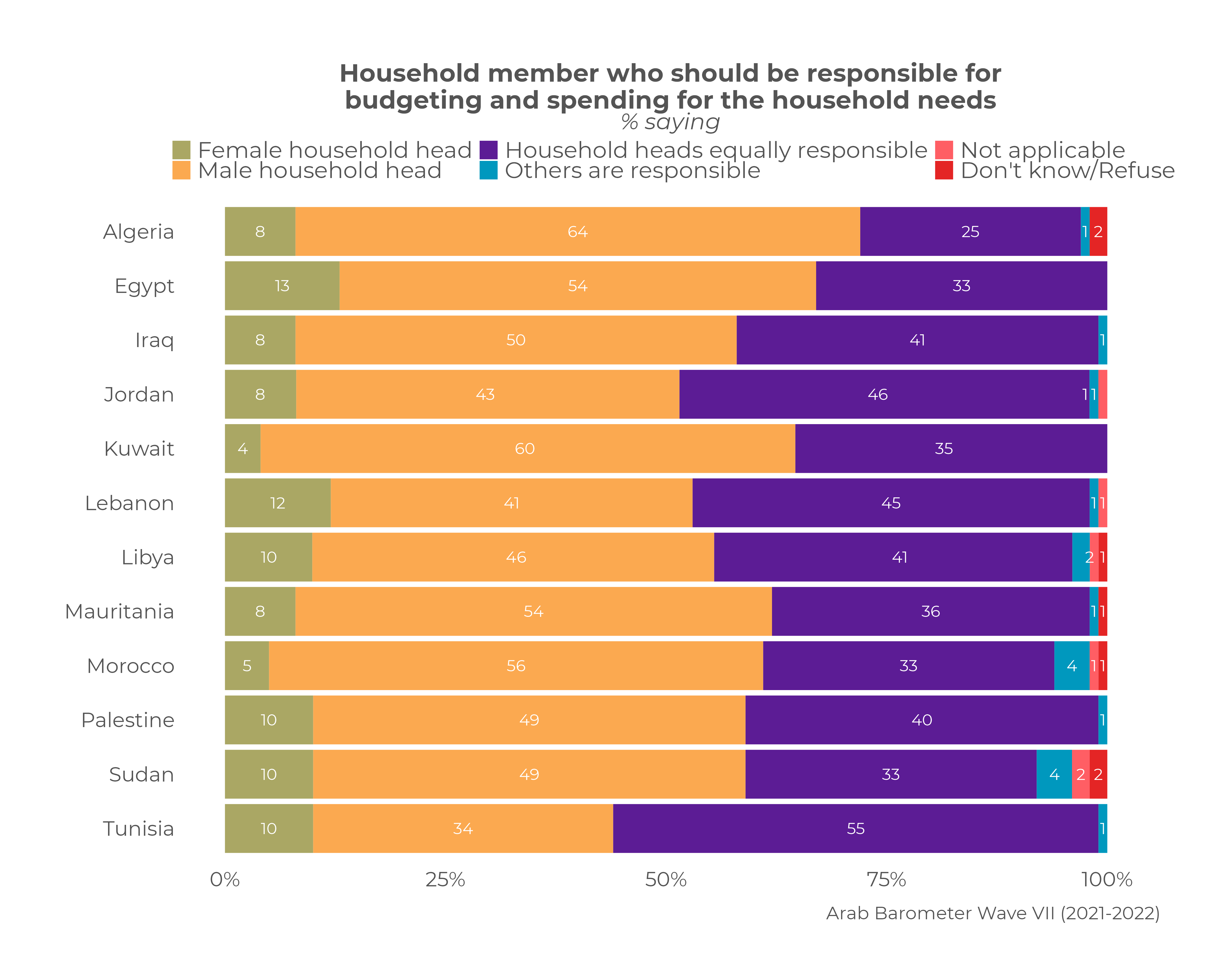

Arab Barometer findings from 12 countries surveyed in the seventh wave (2021-2022) partially confound expectations on unpaid care work in the region. Where it is often assumed that childcare—including help with schoolwork—is relegated exclusively to women, survey results instead suggest that most citizens believe helping children study is a responsibility that should be shared by both male and female household heads, regardless of who currently completes this responsibility. But patriarchal expectations linger when it comes to financial decisions: in most countries, the largest share of citizens believes that the male household head alone should be responsible for budgeting and spending on household needs.

Beliefs about ownership of these responsibilities differ significantly (if not expectedly) between men and women; between more and less educated citizens; and between employed men and employed women. Women and those with higher levels of education are likelier than their male and less educated counterparts to opine household heads should be equally responsible for both tasks. And in comparison to employed men, employed women strongly voice an expectation of equal say in budgeting and spending in particular.

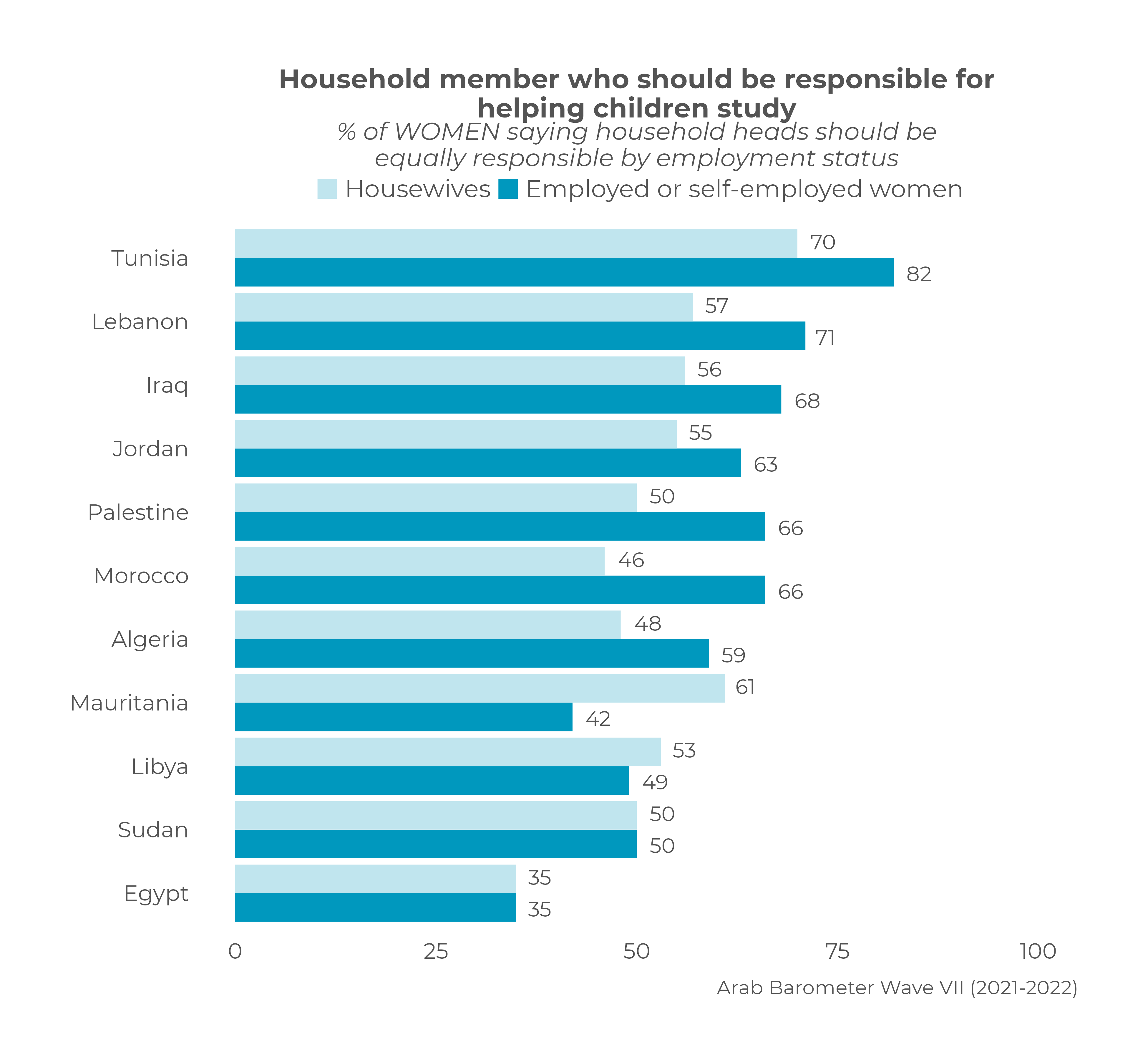

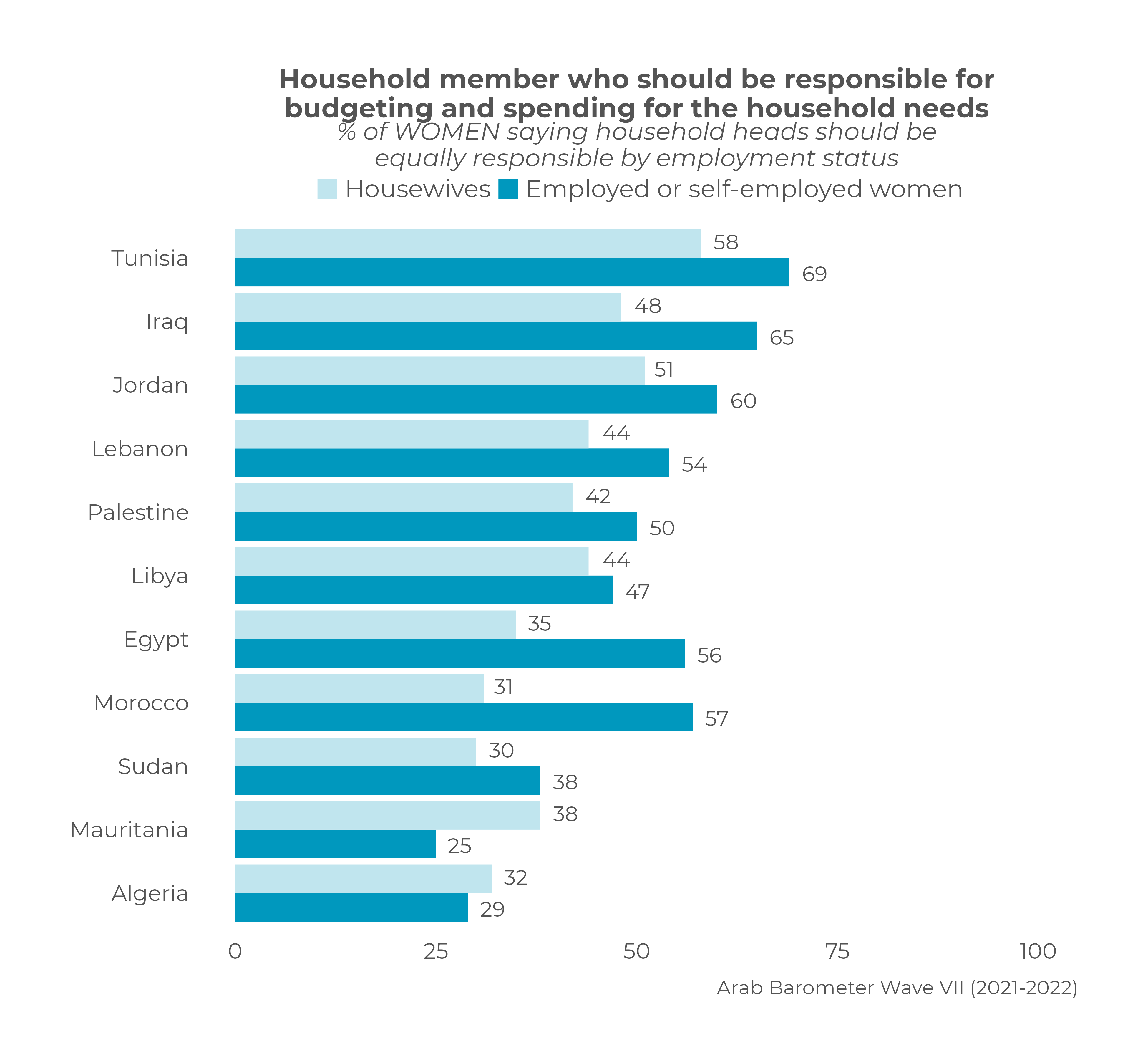

But perhaps what is most notable are differences among women themselves. In most countries, housewives are simultaneously likelier than employed women to say that the female household head should be responsible for helping children study, while the male household head should be responsible for budgeting and spending. Meanwhile, employed women are likelier than housewives on both measures to say responsibility or these tasks should be divided between household heads.

These findings suggest that some gendered norms are as, if not more, reified among the opinions of women outside the paid labor force as they are among the opinions of men. Men are only slightly more likely than women to say helping children study should be the female household head’s responsibility, and with the exception of Egypt, only minority shares of men hold this belief. That said, men, like housewives, are significantly likelier to say the male household head should be responsible for financial decisions. Notably, this close alignment between the opinions of housewives and men may not exclusively be interpreted as housewives lacking choice but might instead indicate exertion of agency and ownership of roles and responsibilities.

This reaffirmation of views on divisions of labor is salient in MENA in part because of the gendered impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. In a recently published book chapter, members of Arab Barometer’s research team used findings from the sixth wave to highlight how the gendered effects of the pandemic in MENA, as elsewhere in the world, negatively affected both monetized and non-monetized work for women. The pandemic calcified expectations of women’s domestic responsibilities and increased non-paid labor on the one hand while causing women disproportionate setbacks in the paid labor market on the other.

Broadly defined as the services provided to institute care for different populations like children and the elderly, the care economy includes tasks like cleaning houses, shopping for groceries, and helping with education and healthcare. When done domestically or in private homes, much of this work is unpaid and often dismissed as unproductive. It is also largely shouldered by women. The informality of this sector is deemed a missed opportunity for economic development, as the care economy is predicted to create jobs and have a positive significant impact on countries’ GDPs. COVID-19 put significant pressure on this “less visible” part of the economy, yet the strain of the pandemic on unpaid care work received less attention than on paid care work (also mostly shouldered by women).

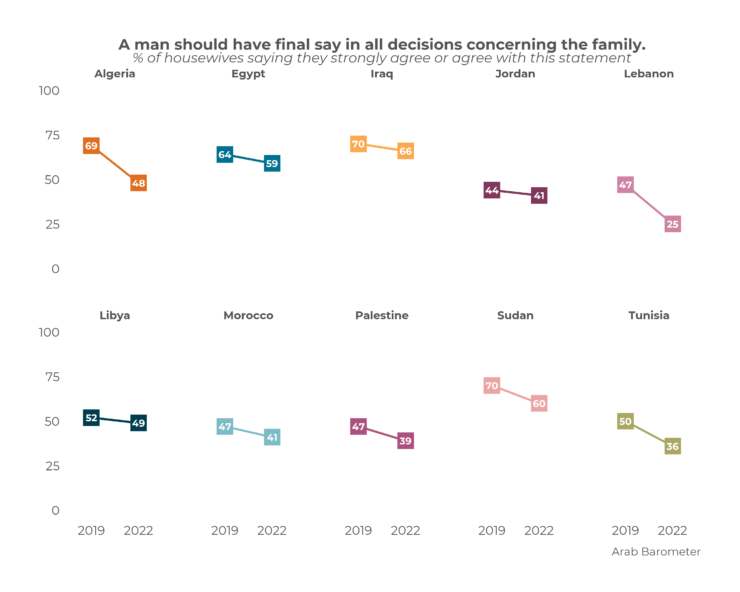

At least one of the COVID-19-driven trends has continued: majorities of housewives in seven out of 12 countries in Arab Barometer’s seventh wave report that the amount of housework they have to do has continued to increase since the beginning of the pandemic. But in several countries, reports of increased household responsibilities borne by women are accompanied by decreased agreement on the statement that men alone should have final say in household decisions. In Egypt, Lebanon, Iraq, and Jordan, decrease in support for this statement is significantly more dramatic among women overall than men.

Housewives are no exception to this trend. Among this subset of women who are often most responsible for unpaid care work, support for the idea that men should have final say in household decisions is markedly down by 22 points in Lebanon, 21 points in Algeria, 14 points in Tunisia, and 10 points in Sudan. The pandemic seems to have had a paradoxical consequence: while it increased the amount of work for women at home, it simultaneously raised awareness for the fact that such work, even if unpaid, merits women having a say in household decisions.

Nearly half of citizens or more in nine out of 12 countries say household heads should be equally responsible for helping children study. Only in Egypt does the majority say this task should be the female household head’s exclusively. This finding varies by gender and education, with more Egyptian men saying it should be the female head’s responsibility (+12 points), and with those with higher education being 6 percent less likely to say that it should be the female head’s responsibility.

In contrast, the results reaffirm preconceived patriarchal expectations when asked about budgeting and spending household responsibilities. Nearly half or more citizens in nine countries attribute this responsibility to the male head. Lebanon, Jordan, and Tunisia stand out, as pluralities in the former two countries and an outright majority in the latter challenge these patriarchal expectations.

Views on ownership of this financial responsibility significantly vary by gender, but the issue is notably polarized along gender lines in five countries. Overall, men are more likely to think the male head of household should be responsible for budgeting and spending, while women are more likely to believe that the responsibility should be shared. In Iraq, men are 21 points more likely to say men should be responsible while women are 17 points more likely to say the household heads should share responsibility. While there is a 15-point gender gap in the belief that men should have most responsibility in financial decisions in each Egypt and Tunisia, women are respectively 10 and 13 points more likely to think household heads are equally responsible. Jordan (+14 points men, male responsible; +11 points women, equally responsible) and Morocco (+13 points men, male responsible; +11 points women, equally responsible) follow the same pattern.

More poignant still are differences between employed men and employed women on attitudes towards financial decision-making responsibilities. In all countries except for Mauritania, employed and self-employed women are more likely than employed and self-employed men to say household heads are equally responsible for household budgeting and spending. This gender gap ranges from 8 percent in Sudan to 32 percent in Iraq. These significant differences point to the possibility that upon entering the paid workforce, women become more empowered and expect to have an equal say in household responsibilities, especially with regards to approaching spending and budgeting.

While gender norms might be at play here, other factors may be necessary to consider. Gainfully employed women simultaneously have less time to dedicate to housework and more financial freedom to outsource responsibilities. For the affluent, this often is done by hiring domestic workers through the kafala or “sponsorship” system in the Arab Gulf, Lebanon, and Jordan. The kafala system is one where a domestic worker is hired under a sponsor to live and work in the host country. These workers often live in their employers’ households as nannies, cooks, or cleaners. They rarely have clear job descriptions and are predominantly women.

But hiring domestic workers is potentially a double-edged sword. While the entry of women into the paid workforce might be changing gendered power relations and challenging gender norms within a household, hiring domestic workers who are primarily women reinforces the gender norm at the societal level.

Findings from the seventh wave disrupt patriarchal preconceptions with respect to sharing childcare responsibilities but reinforce them when it comes to insisting that budgeting and spending are the responsibilities of the man of the house. Gender, education, and employment status complicate this overarching pattern further. The ensuing results, which sometimes confirm and sometimes challenge expectations, highlight the importance of nuancing approaches to understanding gender norms in MENA. This calls for further contextualization of individual and country-specific trajectories. The findings also point to potential and important future research agendas on the impact of domestic workers, under kafala or otherwise, on care work and household distributions of responsibilities.