Personal piety is not constant across space or time. The Pew Research Center has found that levels of religiosity vary by a number of factors, including years of education, life expectancy, income, and levels of economic inequality. Others have found that during times of crisis such as natural disasters or terrorist attacks, there tend to be associated increases in levels of religiosity among those who were affected. In part, this is due to the fact that religion offers teaching and mechanisms to help individuals navigate challenges they encounter in life. Globally, the response to the COVID-19 pandemic appears to be no exception, with Google searches for prayer reaching the highest levels ever recorded while data from the U.S. reveals a strengthening in faith resulting from the crisis.

Since its inception, Arab Barometer has been tracking rates of religious observance across the Middle East and North Africa. As in other world regions, data from our nationally representative public opinion surveys have shown changes in personal piety over time. In 2019, the media outlets highlighted small but meaningful declines in religiosity in this region between Arab Barometer’s third wave (2012-2014) and its fifth wave (2018-2019). However, this trend has since reversed. In the seventh wave of surveys (2021-2022), ordinary people across MENA are now less likely to say they are “not religious”, particularly the region’s youth.

Religiosity in MENA

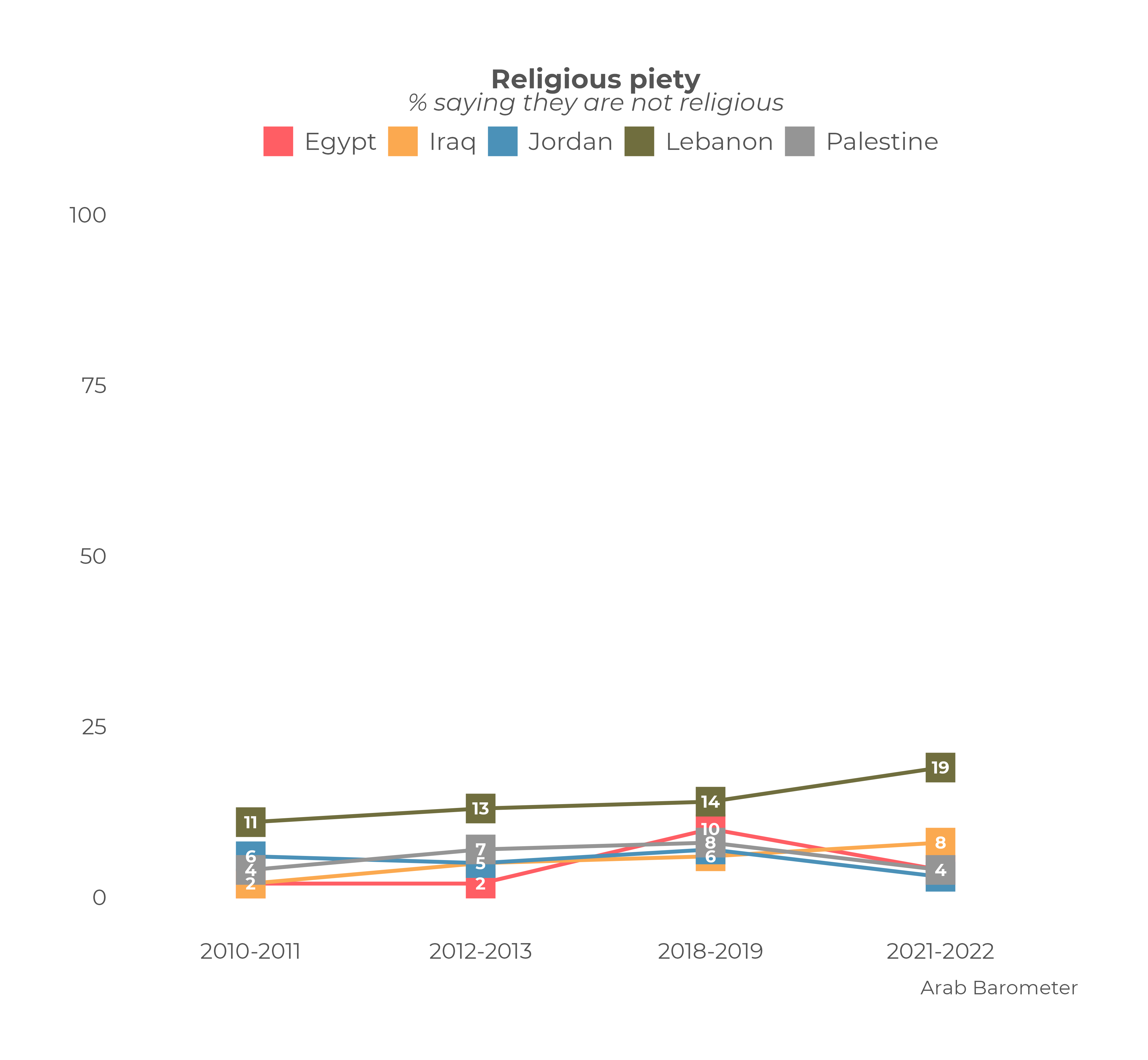

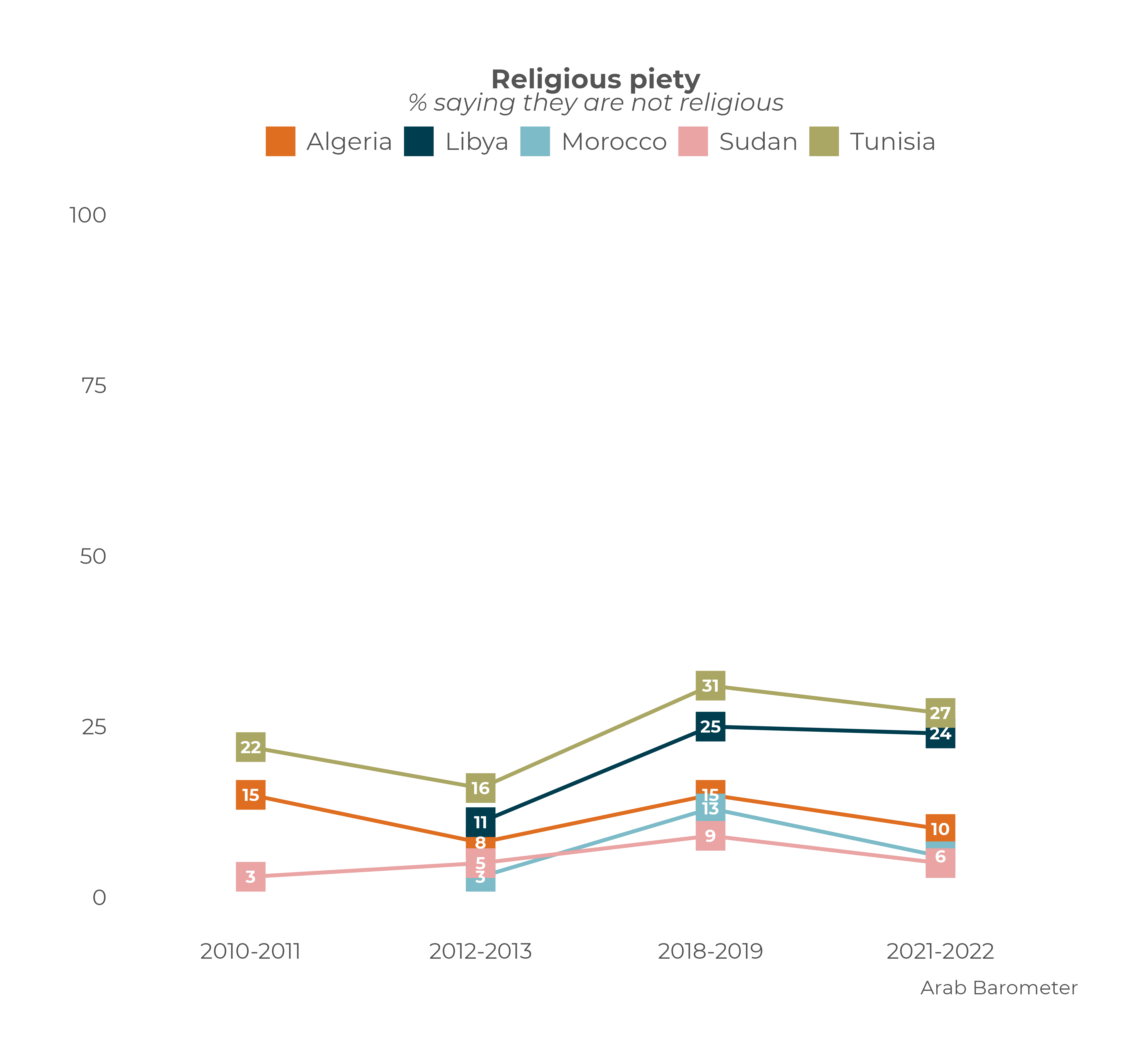

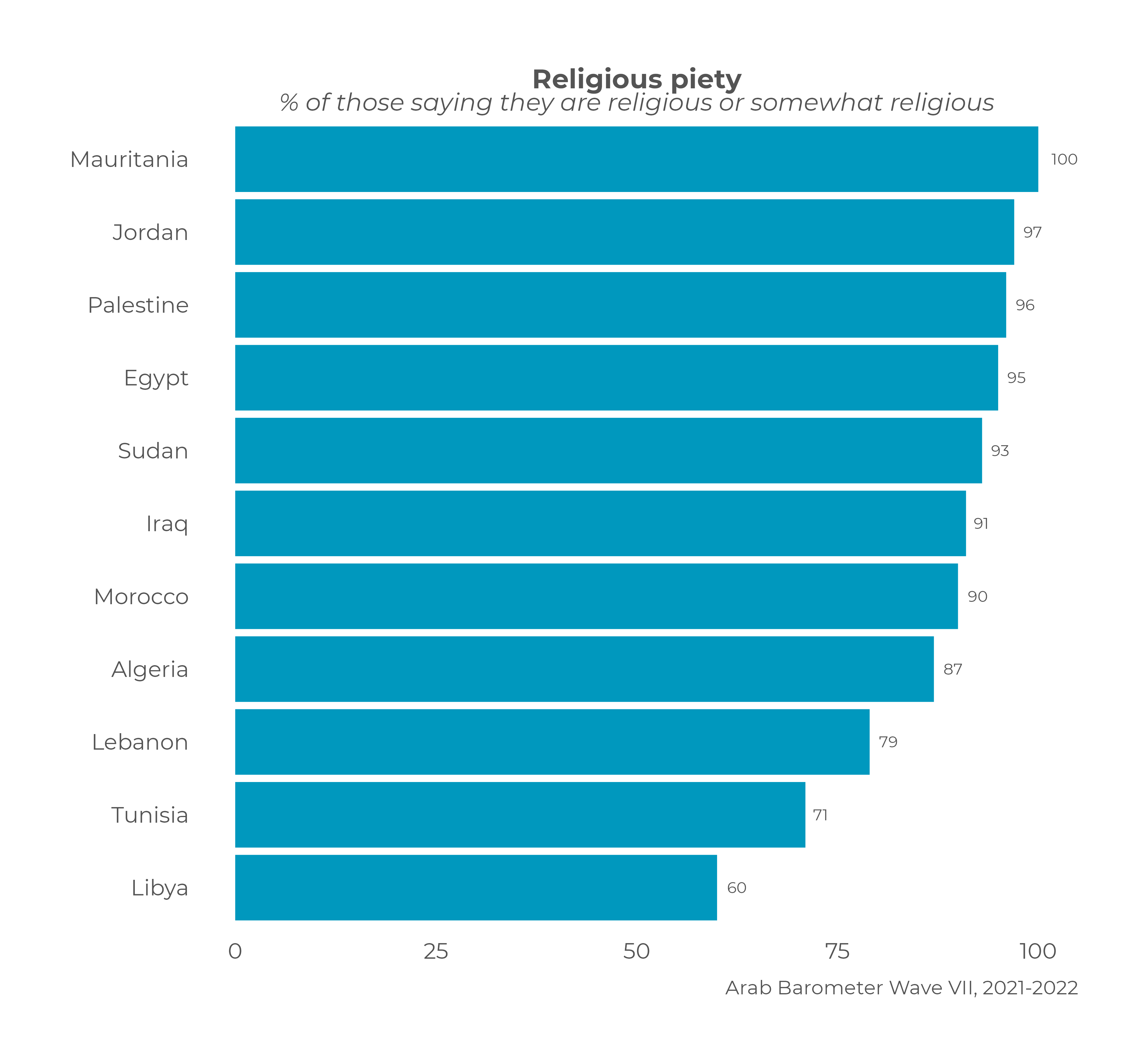

In all countries surveyed across all waves of Arab Barometer, the vast majority of citizens have described themselves as “religious” or “somewhat” religious. However, there are some people who identify as “not religious”. In most countries, this level peaked in the survey wave completed in 2018-2019, with as many as 31 percent in Tunisia and 25 percent in Libya saying they were not religious. Elsewhere, this percentage was lower ranging from as many as 15 percent in Algeria to just five percent in Yemen.

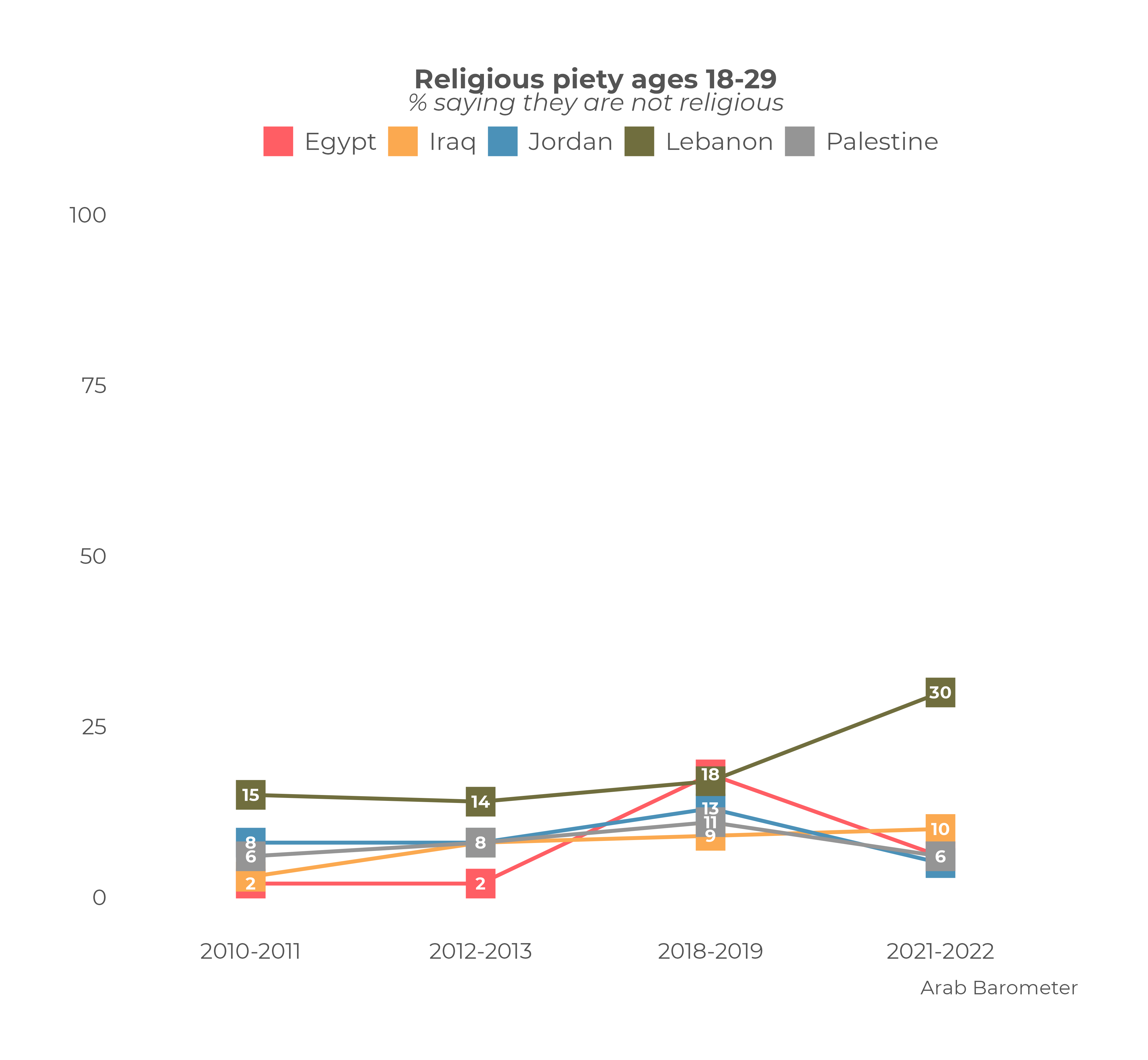

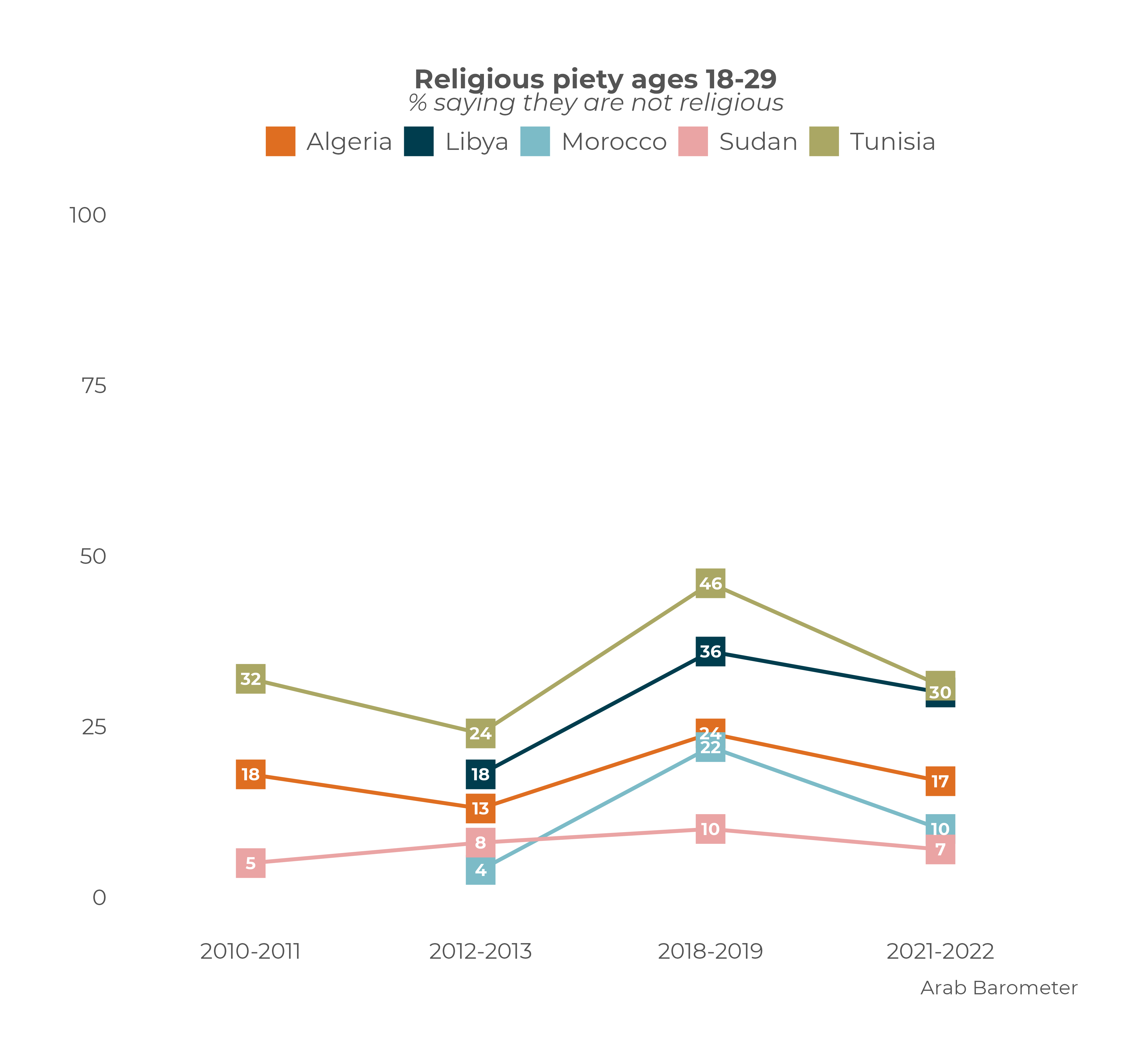

However, in most countries, youth ages 18 to 29 were more likely than those who were 30 years or older to say they were “not religious”. The percentage of youth who were “not religious” was highest in Tunisia (46 percent), followed by Libya (36 percent), Algeria (24 percent), Morocco (22 percent), and Egypt (18 percent). Notably, in multiple countries youth had become far more likely to say were “not religious” since 2012-2014, including in Tunisia (+24 points), Libya (+18 points), Morocco (+18 points), Egypt (+15 points), and Algeria (+11 points). This result led some to question whether MENA would become less religious in the years ahead.

The answer appears to be no, or at least not in the near term. In the most recent wave of surveys (2021-2022), citizens across MENA have become less likely to say they are “not religious”. Tunisians (27 percent) and Libyans (24 percent) still remain the most likely, followed by Lebanese (19 percent). In all other countries surveyed, one-in-ten or fewer say they are “not religious”. Compared to the 2018-19 wave of surveys, these levels represent a meaningful decline, including by seven points in Morocco, six points in Egypt, five points in Algeria, and four points in Jordan, Palestine, Sudan, and Tunisia, respectively. Among the countries surveyed in both waves, only Lebanon (+5 points) and Iraq (+2 points) do not witness a decrease in the percentage of citizens who say they are “not religious”.

Notably, this change is particularly large among youth. In Tunisia, those ages 18-29 are now 15 points less likely to say they are “not religious” compared with just three years before. Elsewhere, there is decline among youth of 12 points in Morocco and Egypt, eight points in Jordan, seven points in Algeria, and five points in Palestine. In Iraq and Sudan, there is effectively no change among youth while only in Lebanon (13 points) does the percentage of youth who say they are “not religious” increase significantly.

The Lebanon exception highlights that the region is far from monolithic in how personal piety is likely to increase or decrease. During this period, the country witnessed a complete collapse of its financial system. The country has long been led by a confessional system whereby power is balanced between those affiliated with different religious communities. As this system failed the country, it is likely that citizens in part blamed the religious system overall. In response, and unlike those in other countries, citizens likely shied away from choosing to self-identify as religious given the role of leaders from different religious communities in the current political crisis.

Religious Practice

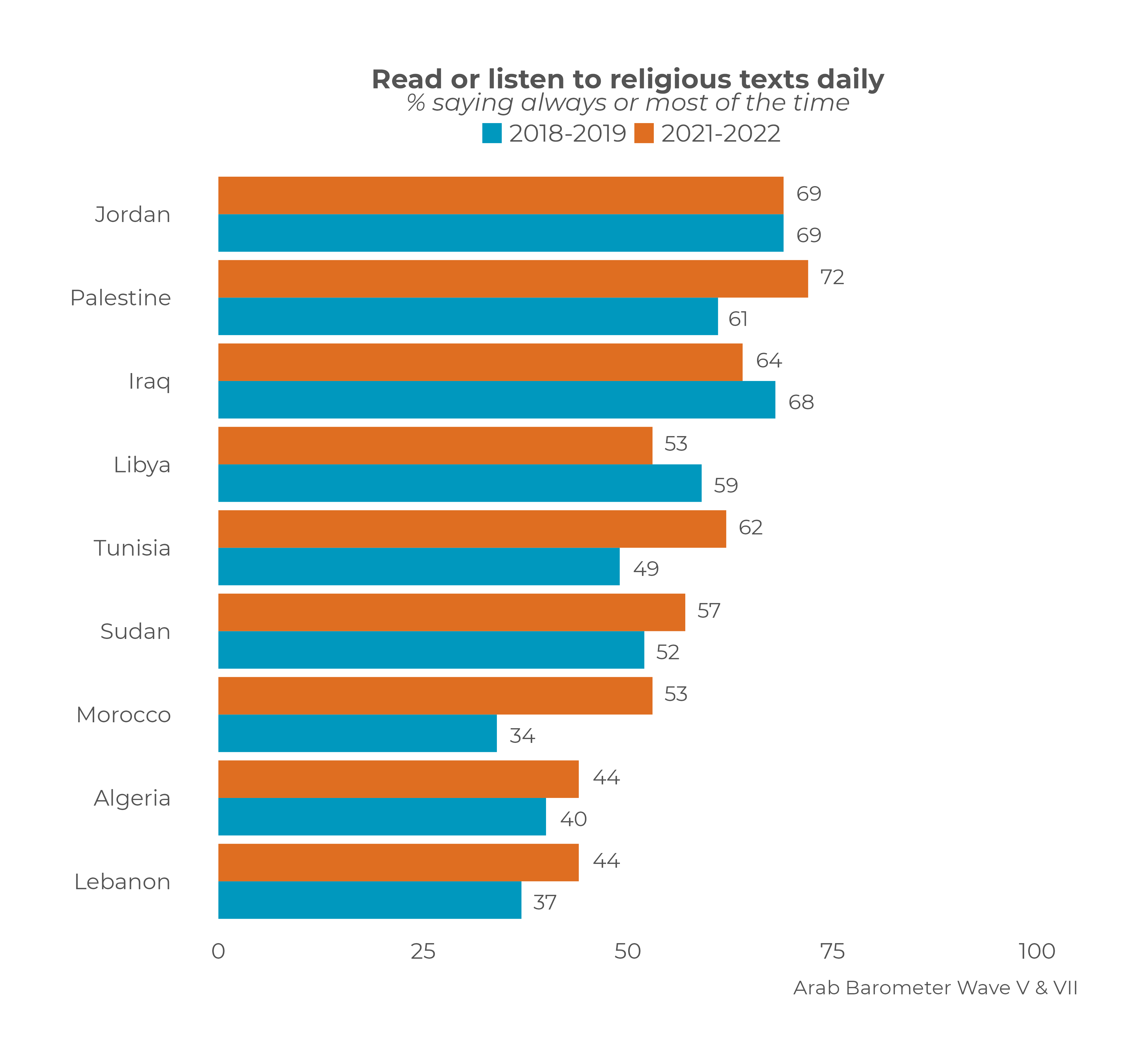

These results are not only found when examining self-identity, but also engagement in religious practices. There has also been an uptick in the percentage of citizens who report engaging in religious texts on a daily basis from 2018-2019 to 2021-2022. When asked if they read or listen to the Quran or the Bible at least once a day, the percentage saying that they do so always or most of the time has increased in a number of countries. For all adult citizens, there have been meaningful increases in Morocco (+19 points), Tunisia (+13 points), Palestine (+11 points), Lebanon (+7 points), Sudan (+5 points), and Algeria (+4 points).

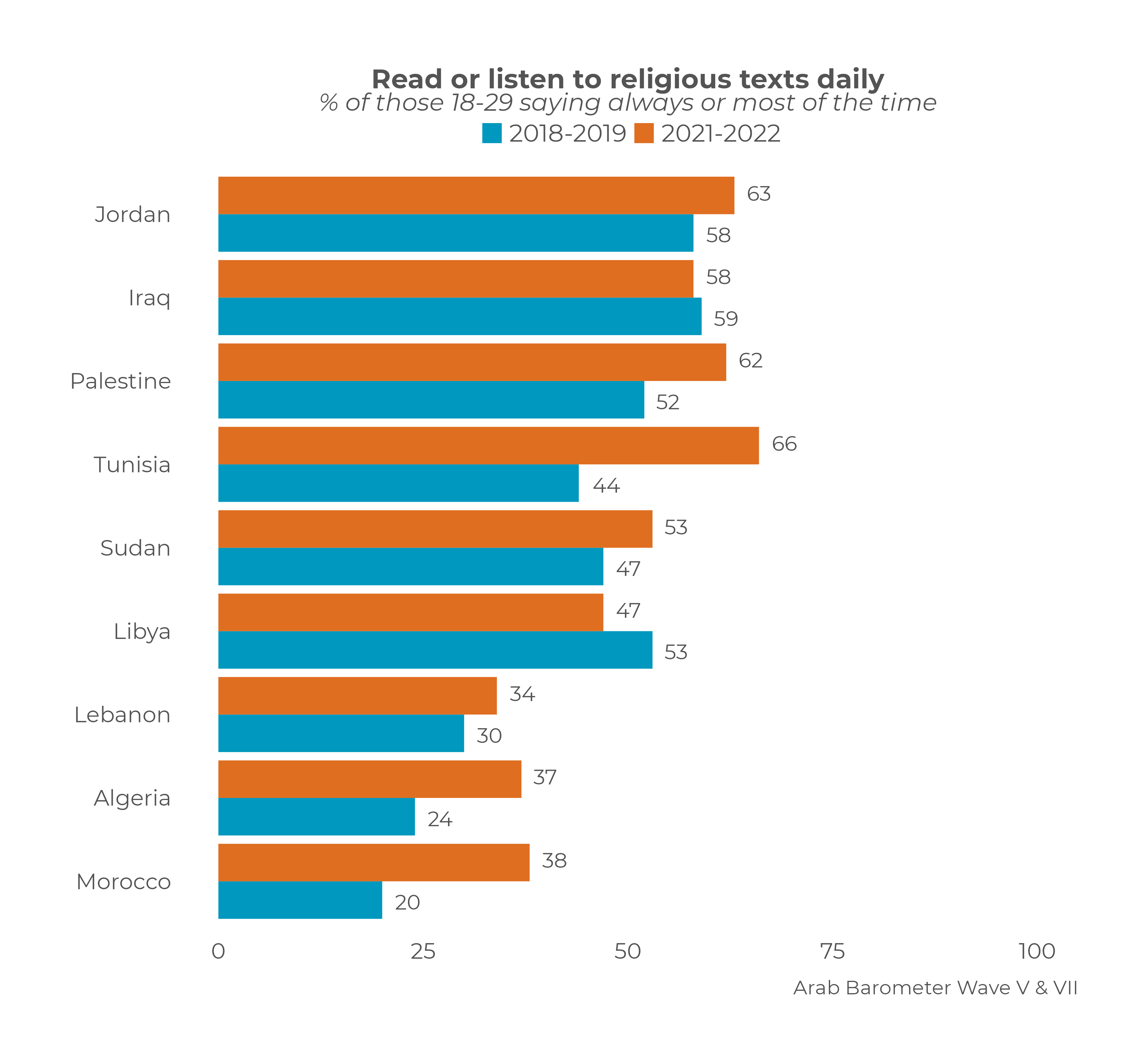

Engagement with religious texts tended to increase to an even greater extent among youth across the region between 2018-2019 and 2021-2022. The corresponding increase is 22 points in Tunisia, 18 points in Morocco, 13 points in Algeria, six points in Sudan, five points in Jordan, and four points in Lebanon. In short, citizens across the region, and especially youth, have seen not only a significant decrease in the degree to which they report being “not religious”, but also there have been corresponding increases in degrees of religious practice.

Takeaways

Around the world, religious identity and practice is not constant, but increases and decreases over time. While the percentage of citizens in MENA, particularly youth, saying they were “not religious” was on the rise in the 2010s, this trend has reversed in the 2020s. This rise in personal piety could be due to many factors, such as the effects of COVID-19, deteriorating economic conditions, or other challenges that make people more likely to turn to religion. Regardless of the exact reason, data from Arab Barometer makes clear that religion continues to play a key role in the lives of most people across the MENA region and likely will continue to do so for the foreseeable future.

Read more on religiosity in MENA in the blog: A New Dawn for Political Islam?