Tunisia, often referred to as the democratic success story coming out of the Arab Spring, has experienced what some are calling a coup following President Kais Saied’s decision to dismiss Prime Minister Hichem Mechichi and suspend parliament. Others say that the president has acted legally under article 80 of Tunisia’s constitution, setting up a significant constitutional crisis. Rached Ghannouchi, the Speaker of Parliament and leader of Ennahda, the largest party in parliament, has vehemently opposed these moves and is, as of this writing, leading a protest outside of the locked parliament.

Although some have portrayed these events as a power struggle among rival ideological camps, results from Arab Barometer suggest otherwise. Rather, discontent about the failure of government to address economic hardships, manage the COVID pandemic effectively, provide quality social services, and eliminate corruption are the deeper causes behind Tunisia’s current crisis. Combined, they help explain the extremely low levels of trust in government, which despite being elected freely, has limited public support, thus creating conditions which have precipitated this crisis.

Nationally representative public opinion surveys from Arab Barometer make clear that ratings of economic conditions in Tunisia are dismal, continuing a downward trend since the revolution of 2011. In all three surveys conducted in Tunisia as part of the sixth wave of Arab Barometer from July 2020 through March 2021, one-in-ten or fewer rated economic conditions positively, including just six percent in March 2021. Economic challenges are also personal, with two-thirds of Tunisians saying they fear losing their main source of income within the next 12 months, implying that most are living in very precarious circumstances. This is especially true among those who are already struggling, with nearly three-quarters (73 percent) of those whose income does not meet their basic needs worrying about this possibility compared with half (51 percent) of those who are better off.

Evidence of the economic challenges are also evident from spending habits of Tunisians. About a quarter of Tunisians (27 percent) say within the past month they have worried that their supply of food would run out before they could afford more, while a similar percentage (25 percent) say that this did happen in the past month. Meanwhile, four-in-ten (41 percent) say they have had to rely on less desired or less expensive foods in the last week to try to make ends meet. An additional 22 percent report needing financial support to pay for food over the same period.

Given the overwhelming nature of concerns about the economy, concern about COVID was relatively limited when the Arab Barometer started fielding its sixth wave. In July 2020, before the first wave of infection hit the country, 59 percent of Tunisians said they were concerned about the spread of COVID. By October of the same year, during the peak of the first wave, Tunisians were substantially more likely to fear the spread of the virus (79 percent), although this rate declined significantly by March following the end of the second wave (56 percent). In sum, Tunisians’ fear of COVID appears to be linked directly to the extent that COVID is spreading in their country. As another wave of the pandemic has struck Tunisia over the past months, concern about COVID has surely once again increased.

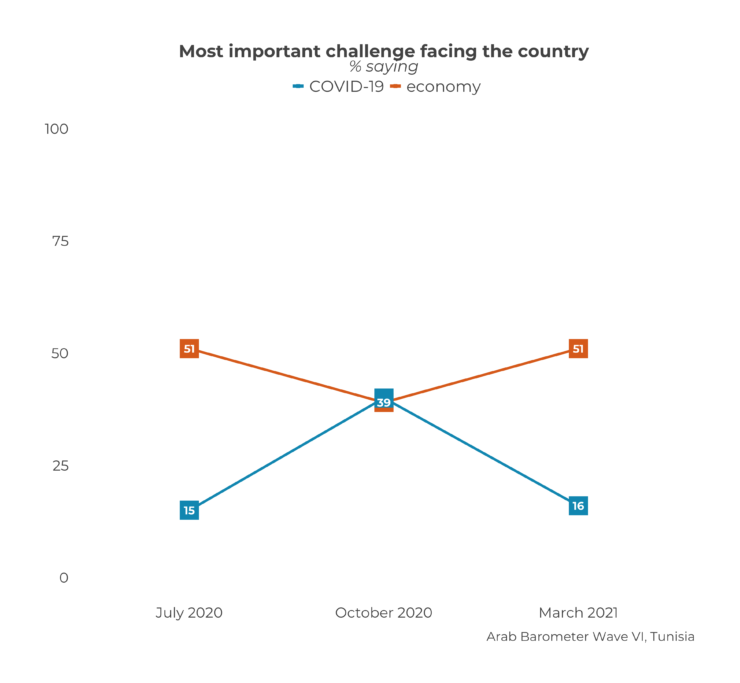

Yet, despite the challenges posed by COVID, Tunisians have not consistently rated it as the country’s top challenge over the past year. In March, relatively few Tunisians said it represented the country’s biggest challenge. Just 16 percent named COVID compared with half (51 percent) saying the economic situation. This represents a notable change from October 2020, during the peak of the first wave of infections, when four-in-ten Tunisians named both COVID and the economy as the biggest challenge, respectively. As COVID rates have risen in recent months, the dual concerns relating to COVID and the economy have combined to place a greater strain on ordinary citizens than at any time since 2011.

Unsurprisingly, Arab Barometer finds that COVID has significantly exacerbated economic problems. Fully a third (34 percent) of Tunisians say that the biggest challenge caused by COVID is rising cost of living, which is a particular concern for those citizens whose income does not cover their expenses (37 percent) compared with those who are better off (30 percent). Tunisians are also keenly aware of the differential effects from COVID on groups that are less well off. Two-thirds (66 percent) say that the effect has been greater on poorer citizens than those who are better off, while half (52 percent) agree that the effect has been greater on migrants compared with others in the country.

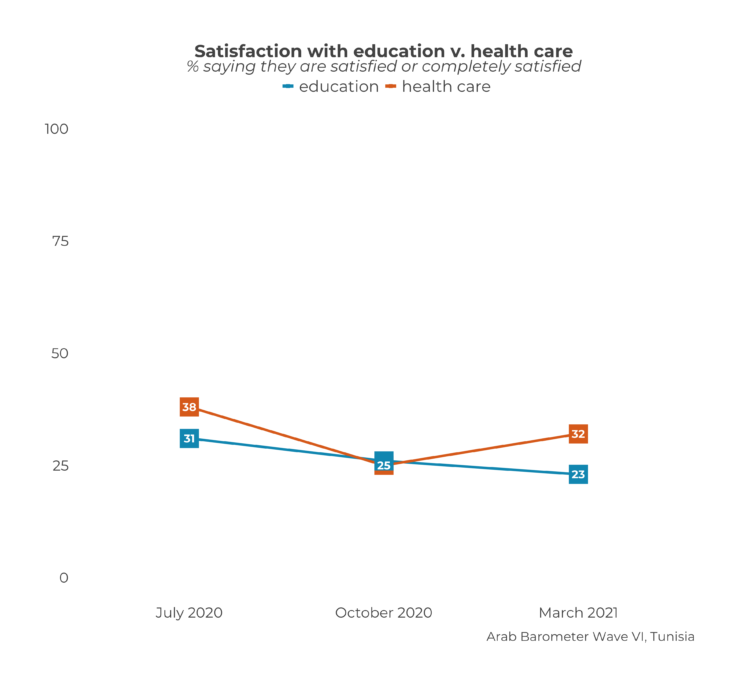

Faith in the healthcare system has also fallen in Tunisia during the course of the pandemic. In the summer of 2020, about four-in-ten citizens said they were satisfied or completely satisfied with healthcare. As the pandemic continued into the first wave, satisfaction dropped 12 points to 26 percent in October 2020 but rose slightly to 32 percent by March 2021. These levels correspond with levels of concern about the virus, suggesting a clear link between ratings of the healthcare system and the ability to manage the pandemic.

Views of the education system has also declined over the past year. Although satisfaction was relatively low to start – just three-in-ten (31 percent) were satisfied in July 2020 – ratings fell throughout the course of the pandemic. In October 2020, 25 percent had a positive view compared with 23 percent in March 2021. As in many countries, the stress of educating children during the pandemic has had important effects on views of the educational system. In effect, it appears that COVID has not only magnified the economic challenges, but also highlighted shortcomings in government services in critical areas like health and education.

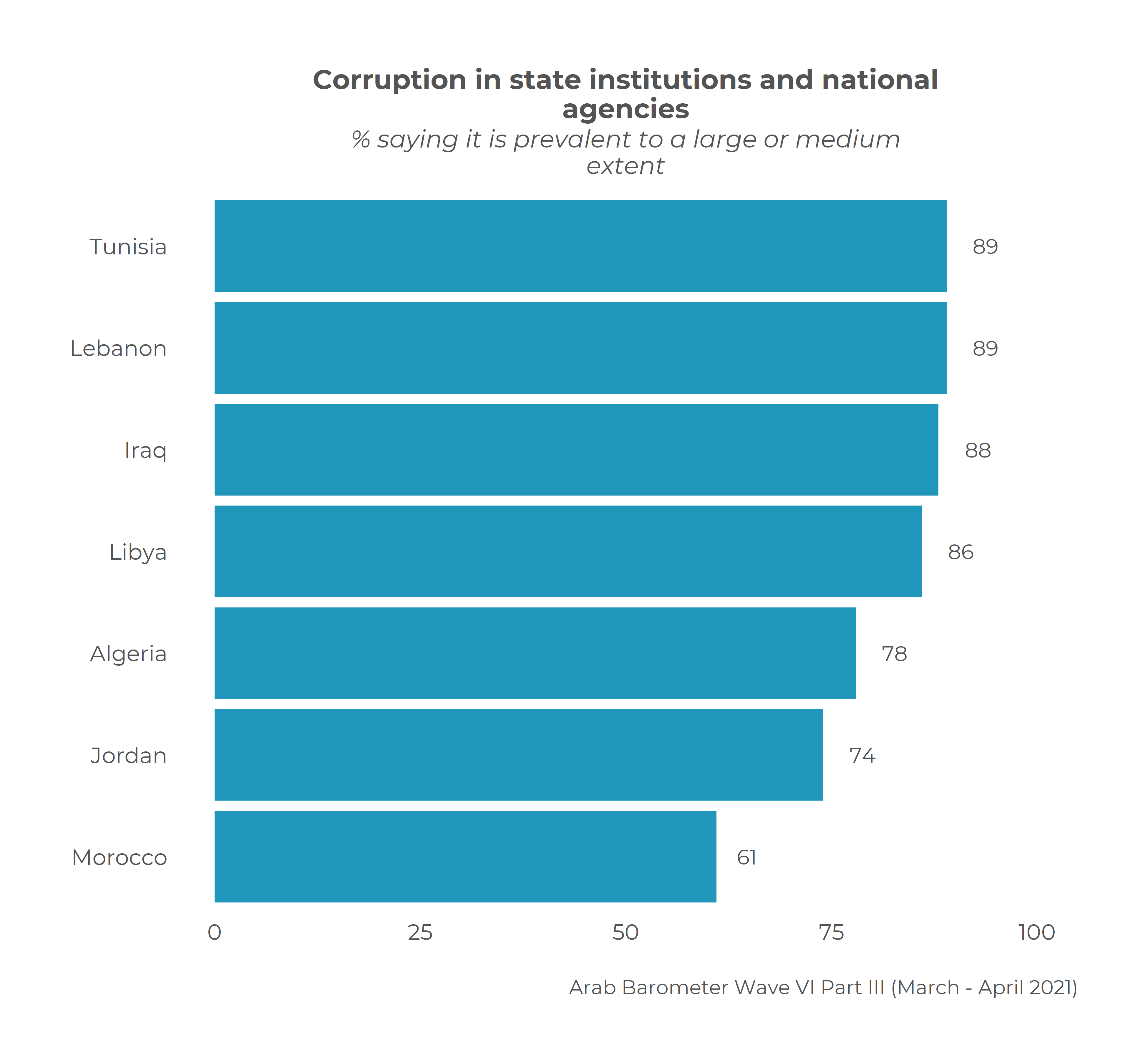

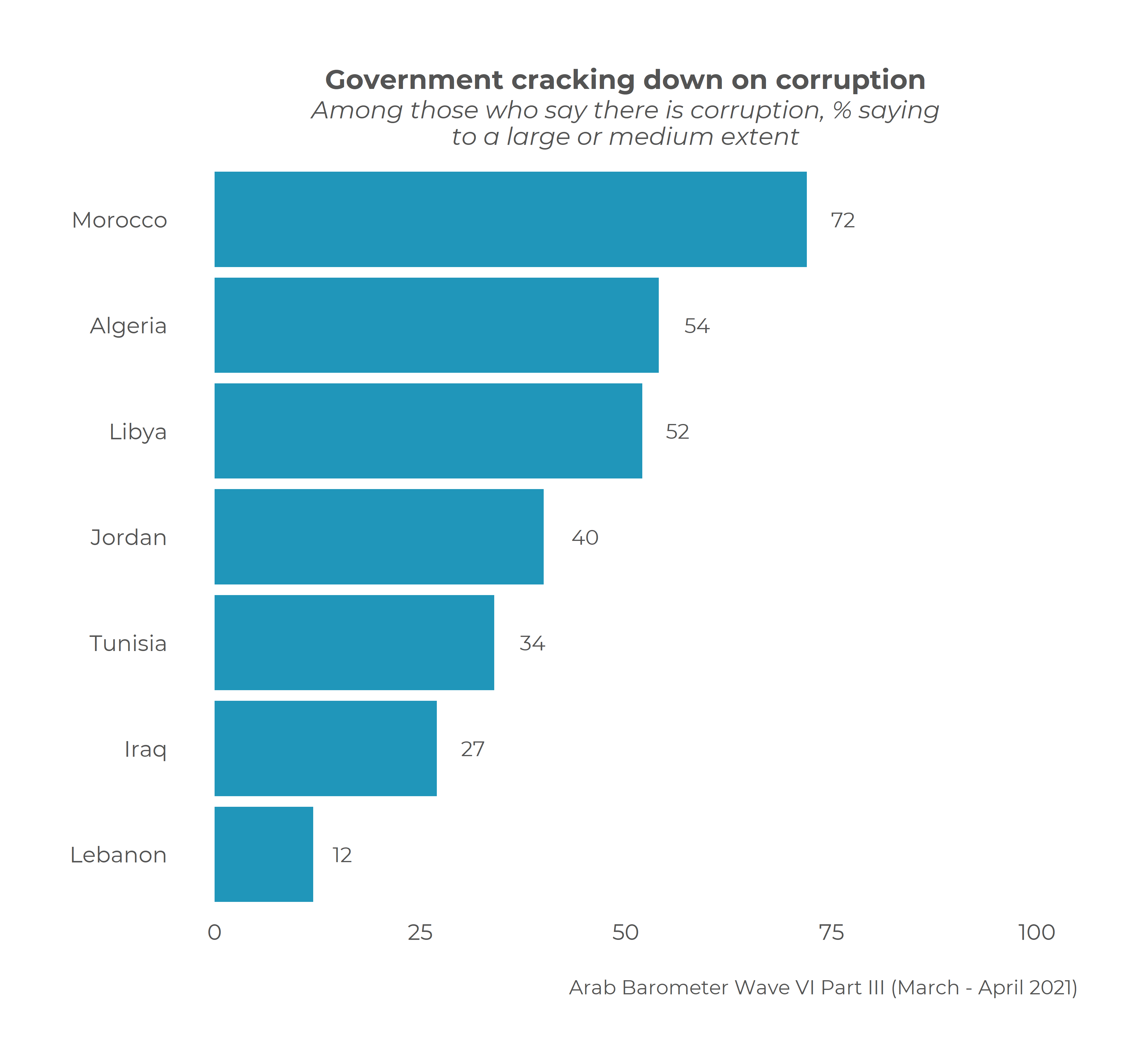

Yet, the largest issue affecting views of government remains corruption. Fully nine-in-ten (89 percent) of Tunisians say that corruption is prevalent to a large or medium extent, which is equal to the highest percentage in any country surveyed in the Arab Barometer sixth wave. Meanwhile, just a third (34 percent) believe that the government is working to address this scourge to a large or medium extent. This perceived failure to tackle what is seen as rampant corruption has thrown the legitimacy of the now sacked government into question, and partially explains the public celebrations of the president’s measures seen in Tunisian streets on July 25.

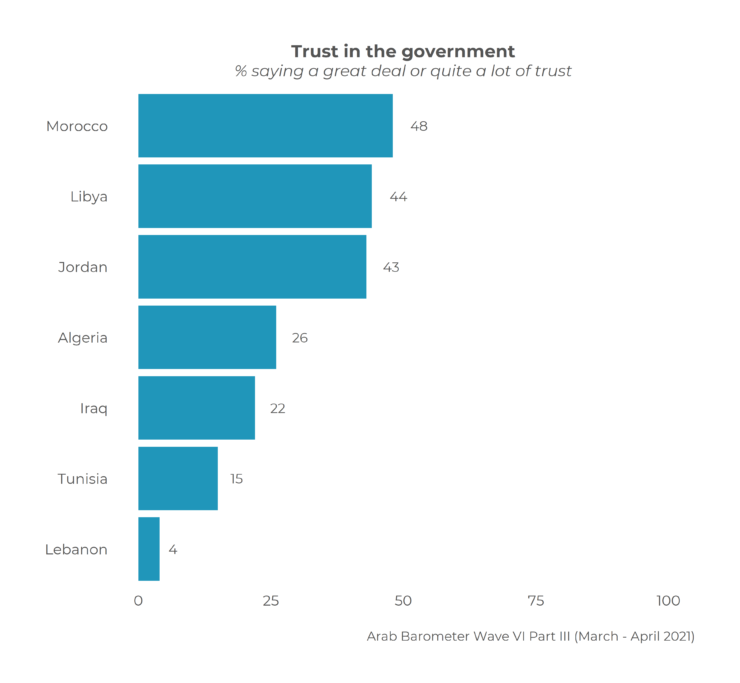

These problems highlight the ongoing failures of governance in Tunisia. Although often referred to as the democratic success story from the so-called Arab Spring, Tunisians’ trust in government has been among the lowest in the Arab region in recent years. Largely unchanged throughout the pandemic, this level of trust has remained very low: 17 percent in July 2020, 19 percent in October 2020, and 15 percent in March 2021. The presidential measures will do little to address these challenges. Tunisians will continue to demand better outcomes from their political system, which has failed to provide meaningful solutions to improve the lives of citizens over the past decade.