The COVID-19 pandemic did not affect everyone equally; every region of the world has reported on the gender disparity of the virus’s toll. This is of particular concern in the MENA region, where women’s rights and roles in the public sphere have been limited by both legal and societal norms.

Given the pre-pandemic status of women in the MENA region, it is perhaps unsurprising that women have been consistently more worried about the COVID-19 pandemic than men throughout the region during Arab Barometer’s Wave VI survey fielding. Notably in Algeria and Lebanon, gendered attitudes regarding pandemic concerns have converged in the most recent survey, while attitudes elsewhere changed mostly in parallel. Beyond the immediate health toll the pandemic took on families, COVID-19 affected women’s roles and responsibilities both at home and in the workplace.

Women at Home

In five out of the seven countries, at least half of all men and women agree or strongly agree with the statement “taking care of the home and children is a woman’s primary responsibility.” In Libya and Lebanon, about one in three women agree or strongly agree with the statement. Lebanon is the only country surveyed where fewer than half of men agree or strongly agree with the statement (35 percent).

Although in most countries men were more likely to agree or strongly agree, the gendered differences are not significant anywhere except Libya. In Libya there is a 40 point different between men and women’s agreement that a woman’s primary responsibility is the home and children; 71 percent of men agree or strongly agree compared to only 31 percent of women.

In some countries, we see a significant generational divide between women ages 18-29 and women over 30 with respect to a woman’s primary responsibility. In Tunisia, Morocco, and Libya, there is at least a 10 point difference between the percent of women 18-29 and 30 and over who agree that a woman’s primary responsibility is the home and children. There is a smaller gap between the younger and older generation in Lebanon (7 points), Jordan (6 points), and Iraq (4 points). Algeria is the only country in which women 18-29 are more likely to agree that a woman’s primary responsibility is home and children than women 30 and over.

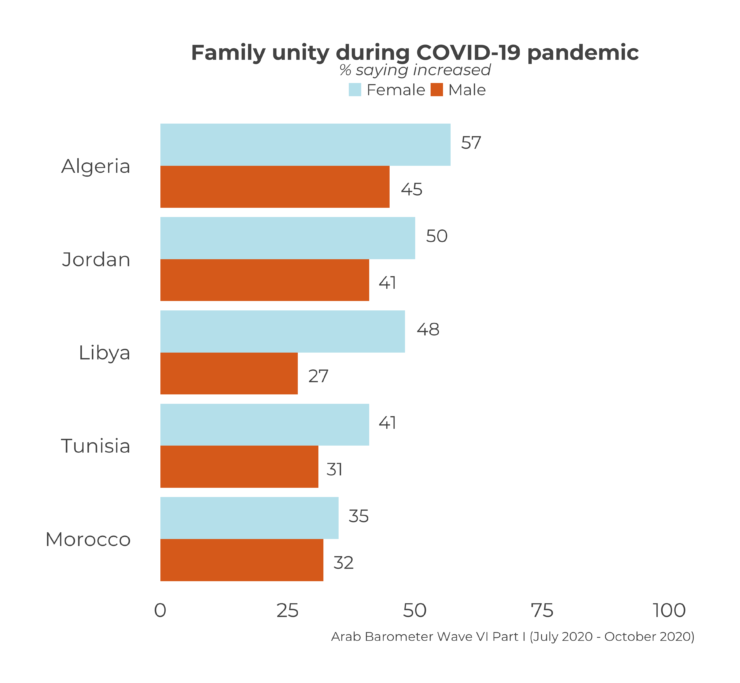

The reality is that women face greater expectations to manage domestic life than their male counterparts and government lockdowns increased home responsibilities. Despite domestic challenges uniquely faced by women during the pandemic, across the region women were more likely than men to say family unity had increased. The increase in family unity can be seen by the relatively low percent of people reporting an increase in verbal arguments among family members during the pandemic. Across the region, similar percentages of men and women report an increase of verbal arguments, just between 20 percent and 31 percent. A final concern for women at home during the COVID-19 pandemic is the threat of domestic violence. National lockdowns force women to share more time with their abusers.

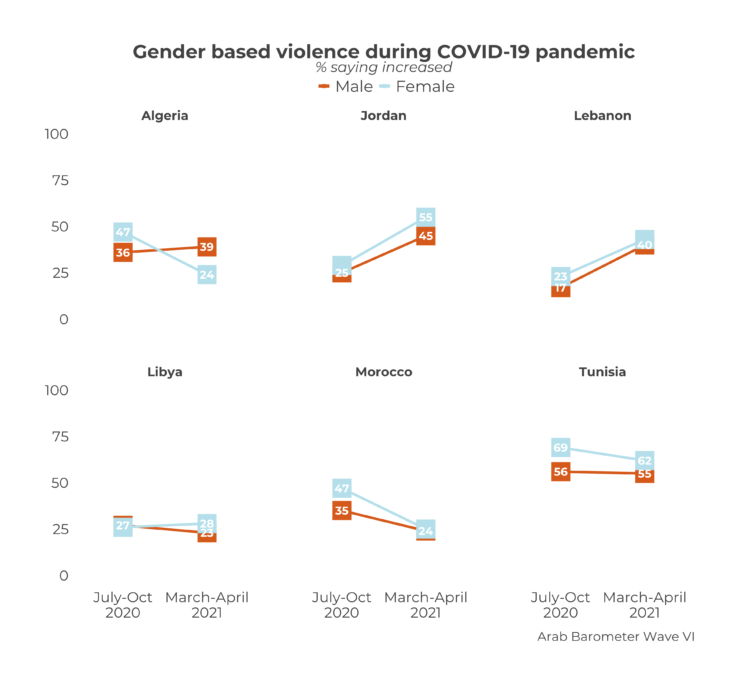

Despite most women (and men) reporting that questions of changes in familial physical violence were not applicable to their situation, at least a quarter of women in every country reported an increase in GBV in the community during the pandemic in survey 1 of Arab Barometer Wave VI. Nearly half of all women report an increase in Morocco (47 percent) and Algeria (47 percent), as well as over two thirds of women in Tunisia (69 percent). Thankfully, in the final survey of Arab Barometer Wave VI, the percent of women reporting an increase in GBV dropped in all three of these countries (Morocco – 25 percent, Algeria – 24 percent, Tunisia – 62 percent). Unfortunately, the countries where fewer than half the women reported an increase in GBV either stayed relatively stable (Libya – 26 to 29 percent) or dramatically increased (Jordan – 29 to 55 percent, Lebanon – 23 to 43 percent).

Women at the Workplace

The economic strife caused by the pandemic erased many of the gains made by women in the past few years. With labor force participation among women so low to begin with, nation-wide shutdowns across the region were particularly devastating. Therefore, it is important to identify potential barriers women face entering the labor field and begin developing policies to ease those barriers.

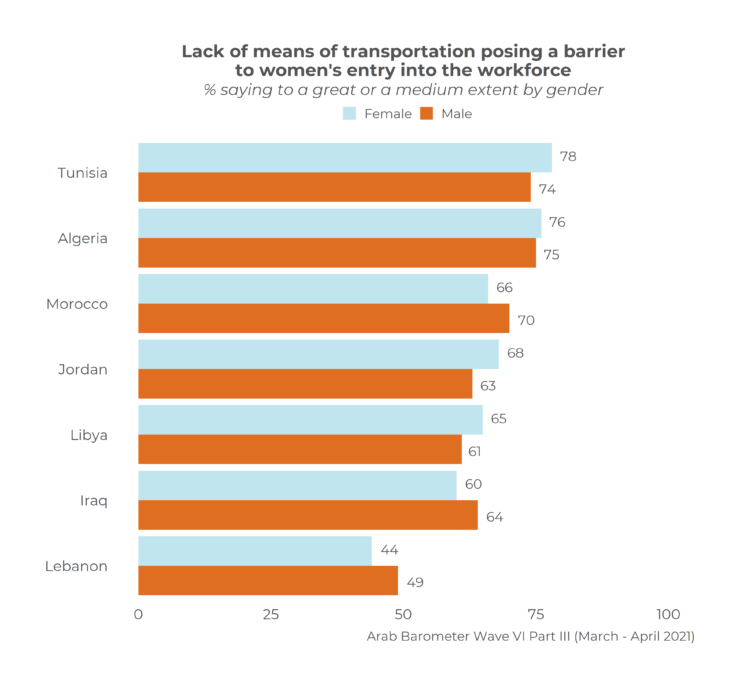

Women view structural issues as more pressing workforce barriers than societal issues. Namely, lack of childcare options and lack of transportation garnered the most support among the issues Arab Barometer offered as preventing women from working. The percent of women saying lack of childcare options posed a barrier to a medium or great extent ranged from 67 percent in Libya to 81 percent in Jordan. Similarly, the percent of women saying that lack of transportation posed a barrier to working to a medium or great extent ranged from 44 percent of women in Lebanon to 78 percent of women in Tunisia. Lebanon was also an outlier here; as Iraq was the next lowest percentage of women at 60 percent. More than half the women in every country also agree that low wages deter them from entering the workforce.

Lack of childcare, lack of transportation, and low wages are all issues governments can develop policies to counter. Barriers related to societal norms are more difficult to overcome. The good news is that despite between 30 and 60 percent of women in most countries in the region completely or somewhat agreeing that men and women should be separated in the workplace, far fewer saw mixed-gender workspaces as a barrier to entering the workforce in the first place. Furthermore, in most cases men see mixed-gender workspaces as more of a barrier than women do.

There could be several reasons women do not see working alongside men as a barrier to joining the workforce. On one hand perhaps many women feel sufficient numbers of gender-segregated workplaces already exist. On the other hand, although women prefer not to work alongside men, they may not feel strongly enough about the issue to keep them from working. Hopefully data gathered in Wave VII will shed light on these responses.

The more pressing normative issue, identified by both men and women, is men being given priority for employment over women. In every country, across both genders, citizens are more likely to say the prioritization of men over women for jobs poses a barrier to women entering the workforce than mixed-gender workspaces. Given that more than half of men in most countries believe that a woman’s primary responsibility is taking care of the home and children, equality in hiring may be a difficult goal.

As economic activity picks up after the pandemic disruptions, the governments of MENA will need to make special considerations on how to help women re-join the workforce – or to join it for the first time.

Check out Arab Barometer’s infographic on barriers to women’s entry to the workforce in MENA.