“Health cannot be bought at the supermarket,” Hans Rosling once reminded audiences in 2006 when discussing health data and development in countries in the Arab region, among others. The famed physician and former professor of international health at Sweden’s Karolinska Institute continued, “You have to invest in health. You have to get kids into schooling. You have to train health staff. You have to educate the population.” During the COVID-19 pandemic, MENA publics resoundingly agree.

Arab Barometer’s sixth wave reveals that citizens in six countries surveyed are judging their governments’ responses to the pandemic by two main factors: the quality of the healthcare system and the handling of the pandemic’s effects on the economy. Unsurprisingly, where publics assess both factors positively or both factors negatively, the overall assessment of the government’s pandemic response is commensurately highest or lowest. Morocco on one end and Lebanon and Tunisia on the other bookend the spectrum of evaluations of the government’s pandemic response. But where evaluations of the two factors are mixed, as is the case in Algeria and Jordan, it appears that citizens are placing a premium on higher marks for healthcare systems when evaluating the government’s overall pandemic response.

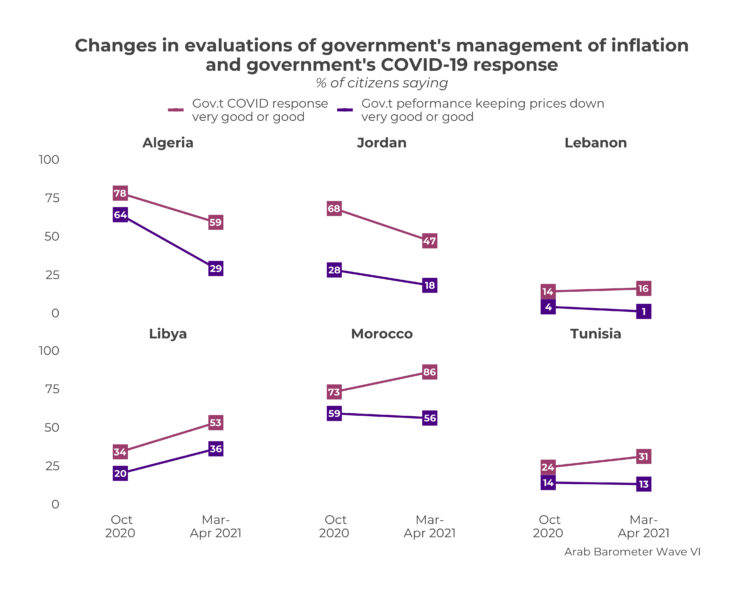

Among countries surveyed, satisfaction with the government’s pandemic response is highest in Morocco (86 percent), where citizens perceive the government has simultaneously managed the economic and health effects of COVID-19 fairly well. In March-April 2021, about half Moroccans report being satisfied with the country’s healthcare system (52 percent), a small, 6-point decline from ratings in July-August 2020 when COVID-19 cases had not yet peaked. (They did so in November 2020). Additionally, a slight majority (56 percent) in March-April 2021 suggests that the government has done a good job of keeping prices down, though notably, those who cannot cover their household expenses (45 percent) are significantly less likely to say so than those who can cover their household expenses (64 percent).

Two things set Morocco apart from other surveyed countries: First, the government’s vaccine rollout campaign has been efficient. As of this writing, nearly 9.4 million Moroccans have had at least one dose of the vaccine, and citizens are eager to get it. Arab Barometer data reveals that 77 percent of Moroccans are very likely or likely to get the vaccine if made available, the highest share of any surveyed country. Furthermore, nearly half (49 percent) of Moroccans report receiving relief aid from the government, making Morocco the only surveyed country where more than one in five citizens reported receiving aid.

Conversely, in Lebanon (16 percent) and Tunisia (31 percent), rates of pandemic response satisfaction among citizens are lowest across the field of surveyed countries in March-April 2021. Commensurately low are ratings of the healthcare system (17 percent in Lebanon, 32 percent Tunisia) and the governments’ performance on keeping inflation at bay (1 percent in Lebanon, 13 percent in Tunisia). Lebanon’s healthcare system has been in turmoil, and when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the country was already in the throes of a financial crisis: its debt-to-GDP ratio was at 152 percent, and by March of 2021, its inflation rate hit 158 percent, up from 17.5 percent one year earlier. In Tunisia, evaluations of the pandemic response fell drastically between the August and October of 2020 as the country’s COVID-19 cases began to climb; the healthcare system began to buckle; the economy shrank; and unemployment soared.

The premium MENA publics are placing on healthcare systems comes through most clearly in countries where evaluations of the government’s pandemic response falls between these cases. In Arab Barometer’s sixth wave, citizens’ evaluations of the healthcare systems, more so than economic evaluations, seem to prop up overall COVID response ratings.

Jordan, where 47 percent have a favorable view of the response, suffered a recession in 2020 due to lockdowns. Ensuing rises in unemployment and declines in tourism revenue and remittances provide the backdrop against which minorities of citizens have a favorable view of the government’s efforts to control inflation. The shares of those saying the government has done a good job at keeping prices low dropped from 28 percent in October 2020 to 18 percent in March-April 2021. And while Jordanians’ assessments of their healthcare system also have fallen dramatically from 76 percent satisfaction in September 2020, the majority (57 percent) is nonetheless satisfied with the healthcare systems in March-April 2021.

Algeria’s trends are comparable to Jordan’s: while satisfaction with the healthcare system and government performance on inflation management have declined, the former has done so to a lesser extent. In March-April of 2021, 59 percent of Algerians report being satisfied with the COVID response. Simultaneously, just 29 percent say the government is doing a good job of keeping prices low, while a higher 46 percent are satisfied with the healthcare system.

The one country diverging from the trend established in Jordan and Algeria is Libya, though the divergence might be explained by the political context of the country. Just months before the formation of the Government of National Unity (GNU) in March 2021, the Central Bank devalued the Libyan dinar in response to falling oil revenues, which began to alleviate economic hardship. While done before its time, the GNU seems to be benefitting from the move of its predecessor as the share of Libyans favorably viewing the inflation response stands at 36 percent—low but still higher than in October under divided government.

Whereas short-term economic interventions might be quicker or easier to implement, rehabilitating Libya’s healthcare system long embattled by years of fighting and the pandemic-induced flight of many foreign-born healthcare workers will require longer-term planning on the part of the GNU. As such, just 28 percent of Libyans are satisfied with the healthcare system, despite the relatively high share (53 percent) satisfied with the government’s handling of the pandemic. This is potentially is part of a wider honeymoon period the GNU is enjoying and potentially a consequence of its attempt to include the pandemic in the national conversation.

In a global discourse that at times pitted measures to contain the spread of the virus against economic fallout, it increasingly has been the case that managing the healthcare crisis is part and parcel of managing the economic one. Rosling’s talk in 2006 suggested that development was happening faster in places that were “healthy before they are wealthy.” Fifteen years later, this policy prescription appears to be exactly what citizens in the Middle East and North Africa want governments to heed.