The world celebrated International Women’s Day on Sunday March 8. But such symbolic days seem to have little effect on the actual status of women in the world, as a recent United Nations report notes. Despite strides towards greater gender equality, the world body notes there is not a single country that has achieved gender equality.

Moreover, 90% of men and women hold some bias against females. The statistics are alarming: 50% of men thought they had more right to a job than women, a third of respondents in 75 countries felt it was acceptable for men to hit women. In China, 55% of respondents felt that men make better political figures. Even in what used to be regarded as the bastion of liberal democracy, the United States, 39% agreed with the statement that men make better political leaders than women.

Disappointing as these figures are, there is hope if one considers how patriarchy is being overcome in the Middle East North Africa (Mena) region. It is here where patriarchy first developed between 3100 BCE and 600 BCE. It is also the region that has experienced the least gender progress in the world.

The figures are incontrovertible. Given the widely held view that women belong in the domestic sphere, focusing on keeping house and child rearing, there are low rates of participation of women in the labour force. Only 24% of women in the Mena region are employed, whereas the figure for their male counterparts is 77%. Moreover, according to a report of the International Labour Organisation, young women with higher education have less chance of entering employment than their less-educated male counterparts.

This holds negative consequences not only for the household economy and the economy at large but also creates women’s greater dependence on their male family members (husbands, fathers, brothers). In the process patriarchy, built as it is on vertical power relations, is further entrenched.

The absence of women in positions of power is quite glaring in the Mena region. Their absence in governance is made possible by patriarchal attitudes. According to the Arab Barometer, the majority of respondents believe in limiting the role of women in society. In the home, 60% believe that the husband should be the final decision-maker in matters affecting the family. Moreover, only a third of the Arab public believes that women are as effective as men in public leadership roles.

Although the marginalisation and oppression of women is a sad truism of Mena countries, this should not be accepted as a norm. Patriarchy was constructed and can be deconstructed. The challenge for feminists then is to actively resist their marginalisation in conjunction with other progressive players as well as to use the tectonic changes that the Middle East is undergoing — from the penetration of the internet to making common cause with progressive forces in society to open up the democratic space.

Democratic space in this sense does not only mean the fight for the ballot, but also emancipation in every sense — including freedom from patriarchy. There is reason to believe that some of this is beginning to happen in the region. Consider, for instance, how Morocco’s rural women in an effort to get land from conservative tribal authorities, formed themselves into action committees called Sulaliyyates. Not only did these challenge tribal authorities but also women’s subordination in the family and the workplace.

There is reason to believe that women’s experiences in mobilising against authoritarian regimes in the region have resulted in a new consciousness on their part where they see the connection between their own oppression and the need for emancipation of the broader society. When women took to the streets against former president Omar al-Bashir in Sudan it was their awareness of how fuel shortages and inflation brought on by corrupt and inefficient governance were affecting household food security.

After the July 2019 agreement between the military junta and the alliance of opposition parties, there was an effort to force women back into the home to play their “traditional” roles. But women have remained politically active, decrying everything from the persistence of sexual harassment to demanding the prosecution of those involved in wrongdoing from the Bashir era.

Women are also pushing back on the streets of Tehran, Ankara and Algiers. In Tehran, women’s grassroots movements are calling on the Islamic republic to fulfil its promises of social justice and gender equality. Their resistance to patriarchy has taken the form of disobedience, refusal and subversion. Initially their activism sought to reform the rule of the mullahs within the prevailing system spurred on by a reformist president, Mohammad Khatami, who demonstrated greater receptivity to gender equality.

In the past two years, women’s groups in Iran have been increasingly calling for the end of Iran’s post-1979 system of governance as they view such theocracy as antithetical to the cause of gender emancipation. In Ankara, feminists have taken on domestic violence by forming the Purple Roof Women’s Shelter Foundation in an effort to collectively fight abuse in the family.

In Algiers, women have been at the forefront of the protest movement against the establishment of what Algerians term Le Pouvoir — the cabal of generals, businessmen and politicians of the ruling party that govern this North African country. For 19-year-old Miriam Saoud, it was to see the back of this political elite that has impoverished Algerians through their corrupt practices. For 22-year-old political science student Amina Djouadi, it was about real political representation for male and female citizens.

Whereas the presence of this younger generation of women makes sense given the fact that half of Algeria’s population is below 30 years of age, and these bear the brunt of unemployment, older women have also been on the Algerian streets. All five of Nissa Imad’s children are unemployed. Explaining her presence against the barricades she states: “I am here for the young, for our kids. There’s nothing for the young generations. No jobs and no houses. They can’t get married. We want this whole system to go.”

These women see the connection between their daily experience of disempowerment and marginalisation and the broader structural causes, and therefore are seeking the ending of this patriarchal and oppressive political and economic order.

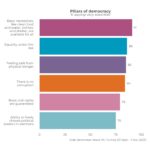

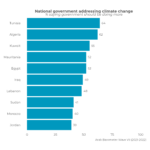

Despite the Mena region having the largest gender gap of all regions in the world, there is hope too. Attitudes are changing and becoming less patriarchal. The Arab Barometer starkly demonstrates this. Seventy-five percent of people in the Mena region support women’s getting tertiary education, 84% believe that women should be allowed to work and 62% believe that women should be allowed into political office.

What accounts for these progressive attitudes? First, there seems to be a generational divide with younger people (who comprise the majority in the Mena region) holding less patriarchal views. Second, those with tertiary qualifications are less discriminatory than those without post-school qualifications.

Hussein Solomon is a professor in the department of political studies and governance at the University of the Free State, a visiting professor at Japan’s Osaka University and a research associate of the think-tank Research on Islam and Muslims in Africa

Read the original article at Mail & Guardian