What drives individuals in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region to pursue self-employment: internal or external personal attributes? How do these factors vary across different countries and economic contexts? This blog presents evidence from a two-level logistic estimation encompassing 12 countries from the MENA region and using data from waves six and seven of the World Values Survey (WVS).[1]

Cultural and psychological factors like Internal Locus of Control (ILC) and religiosity influence the decision to pursue self-employment. ILC, which reflects a belief in personal control over outcomes, encourages risk-taking and entrepreneurship. In contrast, religiosity connects outcomes to divine will, affecting risk-taking differently. Our research shows that while ILC consistently supports self-employment across the MENA region, religiosity’s effects vary based on a country’s economic context and social dynamics, at times enhancing or restricting self-employment.

Religiosity and self-employment: A complex relationship

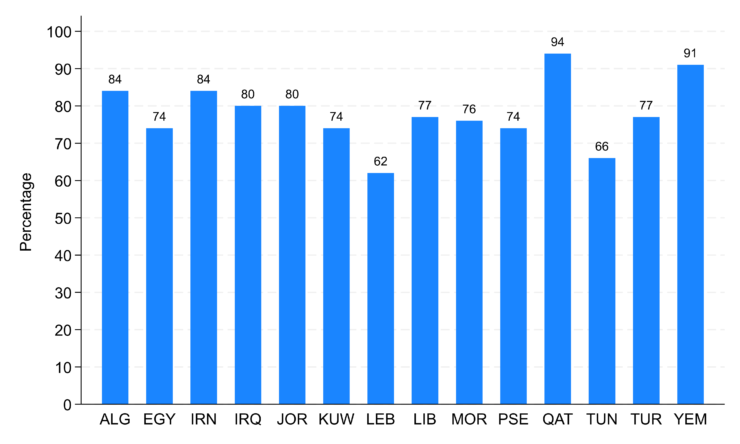

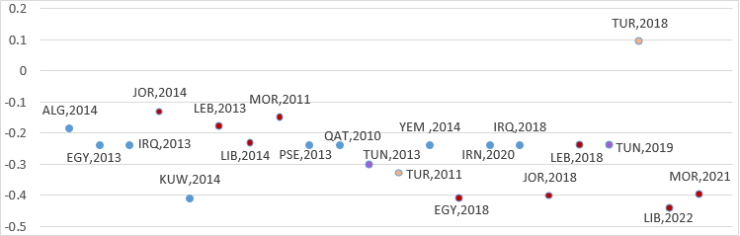

Religiosity is crucial in MENA societies, influencing personal beliefs, social norms, and behaviors. It can promote self-employment by strengthening social networks and community resources but may also hinder motivation if individuals attribute success to divine intervention instead of their efforts. Moreover, as an informal institution, religiosity shapes individual and societal behavior through unwritten norms and beliefs, contrasting with formal institutions like laws. In the MENA region, where an essential percentage of the population self-identifies as religious (see Figure 1), these deeply embedded religious norms are expected to impact attitudes toward self-employment, affecting perceptions of risk-taking and self-reliance.

Figure 1: Percentage of self-identified religious respondents

Note: i) Algeria (ALG), Egypt (EGY), Iraq (IRQ), Iran (IRN), Jordan (JOR), Kuwait (KUW), Lebanon (LEB), Libya (LIB), Morocco (MOR), Palestine (PSE), Qatar (QAT), Tunisia (TUN), Turkey (TUR), and Yemen (YEM).

ii) Data aggregated from waves six and seven of the WVS.

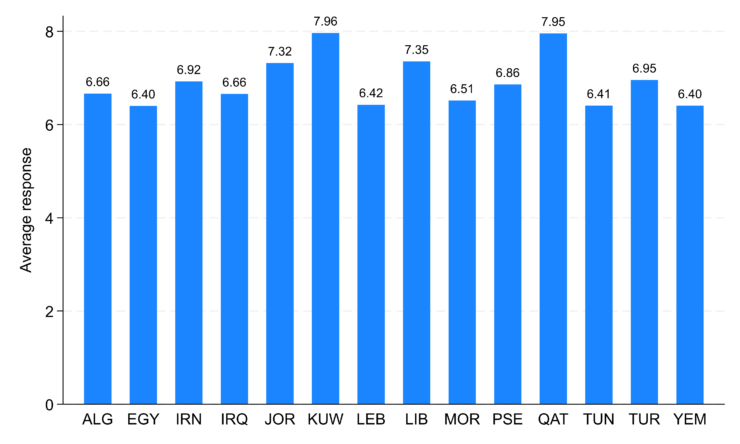

Our research indicates that the impact of religiosity on self-employment varies across countries and over time. Figure 2 shows that this impact became positive in 2018 compared to 2011 in Turkey. The effect became more negative in Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Morocco after 2018 compared to 2011-2014. Conversely, in Tunisia, the impact became less detrimental in 2019 compared to 2013. Thus, our results suggest that religiosity discourages self-employment in most MENA countries. We also find that the magnitude of this effect depends on the socio-economic conditions of each country, specifically real GDP per capita, financial development, tax levels, unemployment rate, and the human development index.

Figure 2: The impact of religiosity on self-employment per country-year

Note: i) Author’s calculation; details are on https://ssrn.com/abstract=5072877.

The consistent impact of Internal Locus of Control (ILC)

Figure 3 illustrates the average responses to the question, “How much freedom of choice and control do you feel you have over how your life turns out?” from the WVS. We observe variations in individuals’ perceptions of control across the sampled countries. For instance, individuals in politically and economically stable nations, like Kuwait and Qatar, report higher levels of personal control than those in politically unstable countries, such as Yemen. They are more likely to believe that their efforts can lead to success compared to those in other MENA countries.

Figure 3: Internal locus of control

Note: i) Data aggregated from waves six and seven of the WVS.

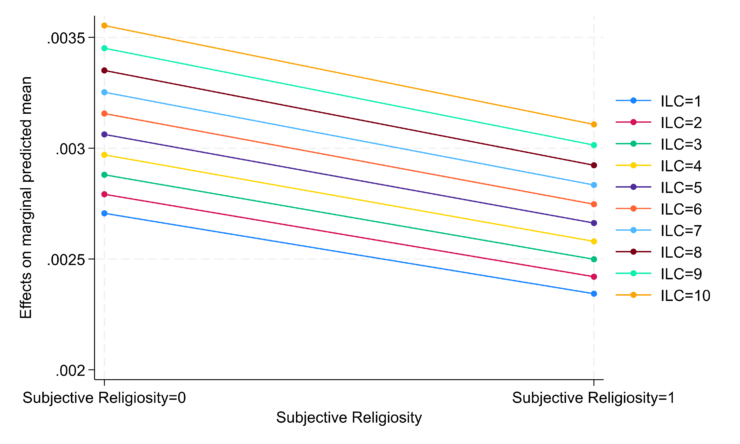

In contrast to religiosity, we find the impact of ILC on self-employment consistent across countries and independent of the country’s level of economic development. Our research shows that ILC consistently encourages self-employment. People who think they can shape their future are more inclined to start businesses, viewing their efforts as the primary driver of success and believing they can control their destiny. This starkly contrasts religiosity, whose effect on self-employment depends on each country’s social fabric and economic conditions. This suggests that ILC has a universal impact, while religiosity is context-dependent and heterogeneous across countries. Interestingly, we also find that individuals who self-identify as religious have a lower impact for ILC on self-employment. This indicates that religiosity lessens ILC’s influence.

Figure 4: The effects of ILC on self-employment conditioned by religiosity

Note: i) ILC is a ten-point Likert scale answer to the question: “How much freedom of choice and control do you feel you have over the way your life turns out?” (1 = none at all, 10 = a great deal).

ii) Subjective religiosity equals one if the respondent answers yes to: “Do you consider yourself a religious person?”.

iii) Author’s calculation; details are on https://ssrn.com/abstract=5072877.

Policy implications

Our study provides policy recommendations for promoting self-employment in the MENA region.

Promoting ILC in entrepreneurship programs:

Given the consistent link between ILC and self-employment, governments and institutions in the MENA region should integrate personal agency, self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial mindset training into education and workforce development programs. This may include policies and programs in entrepreneurial curricula in schools and universities that emphasize problem-solving, risk-taking, and resilience in business. This approach ensures that more individuals in the MENA region are encouraged to pursue entrepreneurship and self-employment.

Tailoring entrepreneurship support based on cultural and religious contexts:

Since religiosity moderates the effect of ILC on self-employment, policies aimed at fostering entrepreneurship should recognize the diverse cultural and religious landscapes of MENA countries. Programs could be designed to reconcile entrepreneurial ambition with religious values, for instance, by promoting Sharia-compliant financing or ethical business models that align with religious beliefs. This alignment between entrepreneurship initiatives and religious values can strengthen the efforts to boost self-employment.

Context-specific policy approaches:

Since religiosity’s impact on self-employment varies across different economic and social contexts, a one-size-fits-all policy may not be effective. Policymakers should adopt a nuanced approach, considering the role of religious institutions and cultural norms in shaping entrepreneurial behavior.

Effective governmental policies:

Governments are encouraged to continue developing effective policies and regulations to foster entrepreneurship and self-employment, especially considering the fragile policy formulation and implementation and the credibility of the government’s commitment. They should dedicate financial resources to encouraging people, especially younger generations, to pursue a career in self-employment.

Importance of education and training:

Policymakers may want to introduce educational and training programs that instill a sense of personal agency, self-efficacy, and resilience in students. Schools and universities could integrate entrepreneurship modules and personality development activities to build skills essential for self-directed careers.

The necessity for community support networks:

Since the MENA region is considered a religious region, with Islam as the dominant religion, people tend to be more risk-averse, which hinders self-employment and, in general, entrepreneurial activities. To support these activities, governments may establish community support networks such as mentorship programs and local incubators. Additionally, they may promote cooperative business structures rather than individualistic ventures. These models would align with communal values by emphasizing risk-sharing and the distribution of responsibilities.

[1] Safari, Arsalan and Bassil, Charbel and Parast, Mahour M., Self-employment in the MENA Region: Locus of Control and Macroeconomic Drivers (December 26, 2024). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5072877. This project was made possible through the support of a grant from Templeton World Charity Foundation, Inc (funder DOI 501100011730) through grant [grant DOI https://doi.org/10.54224/30453]. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Templeton World Charity Foundation, Inc.”

Authors

- Dr. Charbel Bassil, Associate Professor of Economics at the College of Business and Economics, Qatar University, Qatar.

- Dr. Arsalan Safari, Research Associate Professor in Management at the Center for Entrepreneurship and Organizational Excellence, Qatar University.

- Dr. Mahour Parast, Research Associate Professor at the School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment, Arizona State University, the USA.

The views presented in this article are the authors’ own.