Compared to the world’s median age of 28, the median age in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is 22, making the youth a substantial 28 percent of the population in the region. Unemployment rates are increasing as the region’s population grows almost twice as fast as the world’s overall. The quality of life for the youth is thus decreasing, with the rise of inflation, the continued unraveling of the coronavirus pandemic’s implications, and other external/internal factors. These trends highlight the importance of understanding whether the youth, at the onset of such unique challenges, possess subsequent unique perceptions and attitudes towards life quality and the state of their countries.

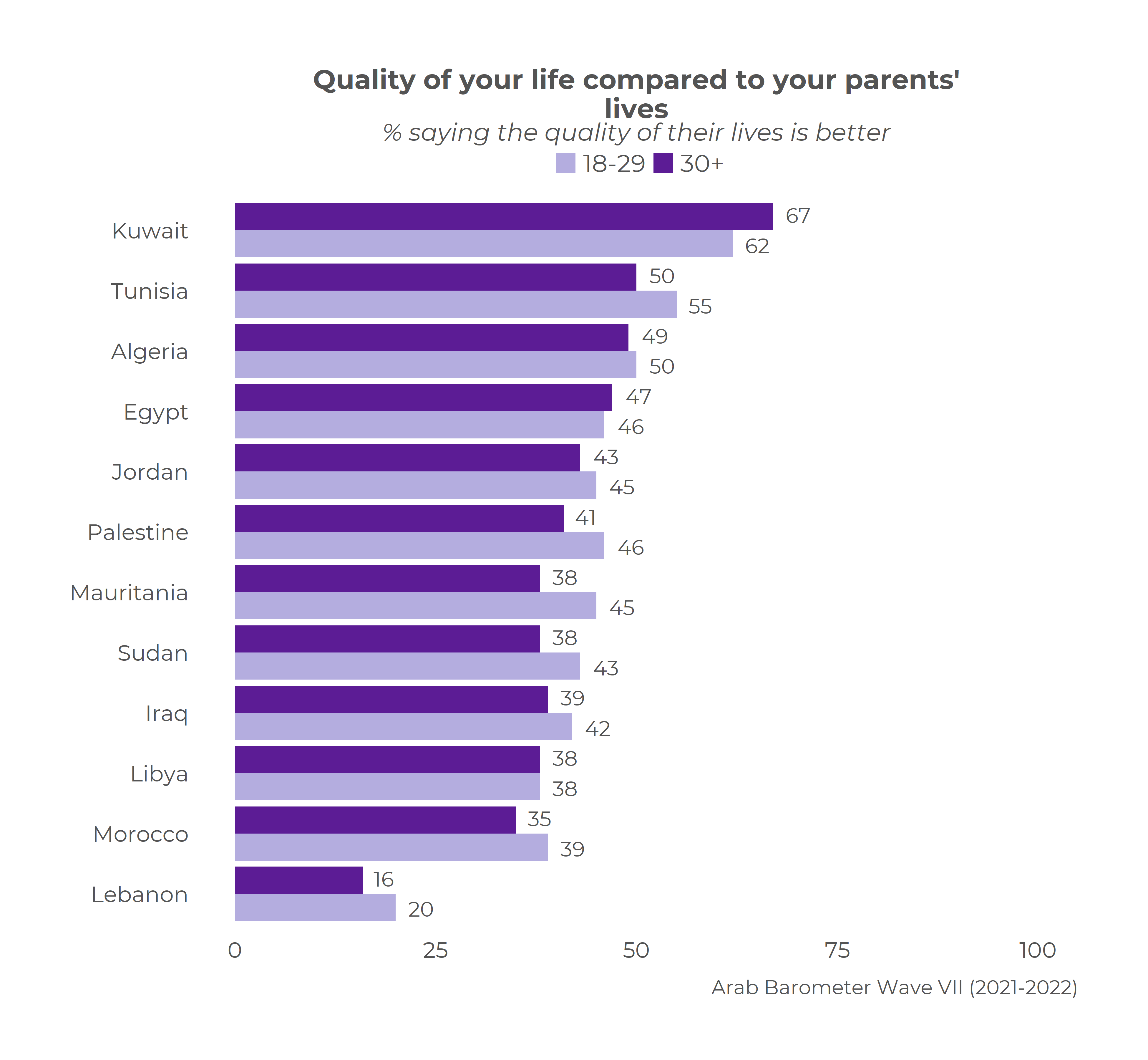

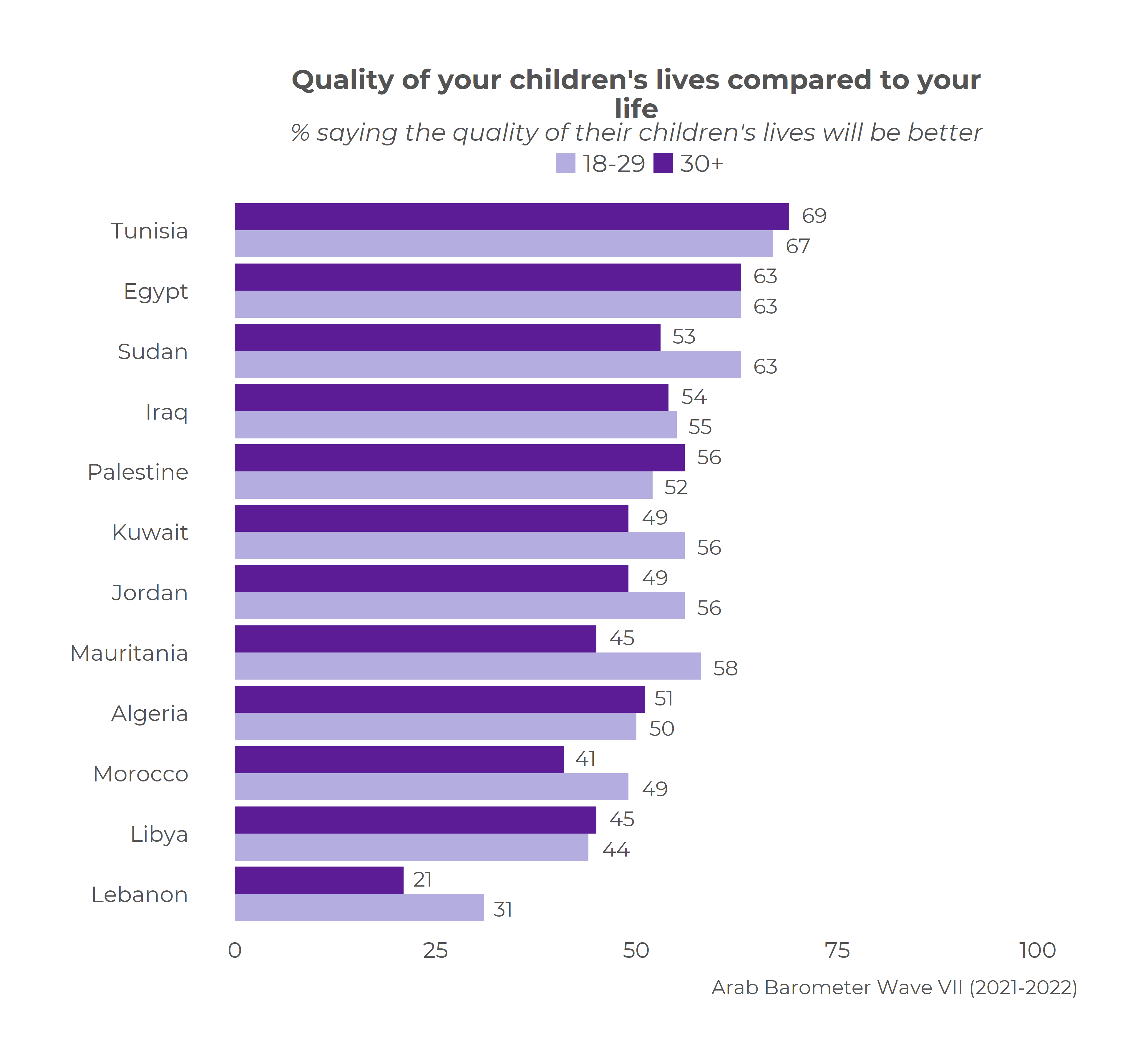

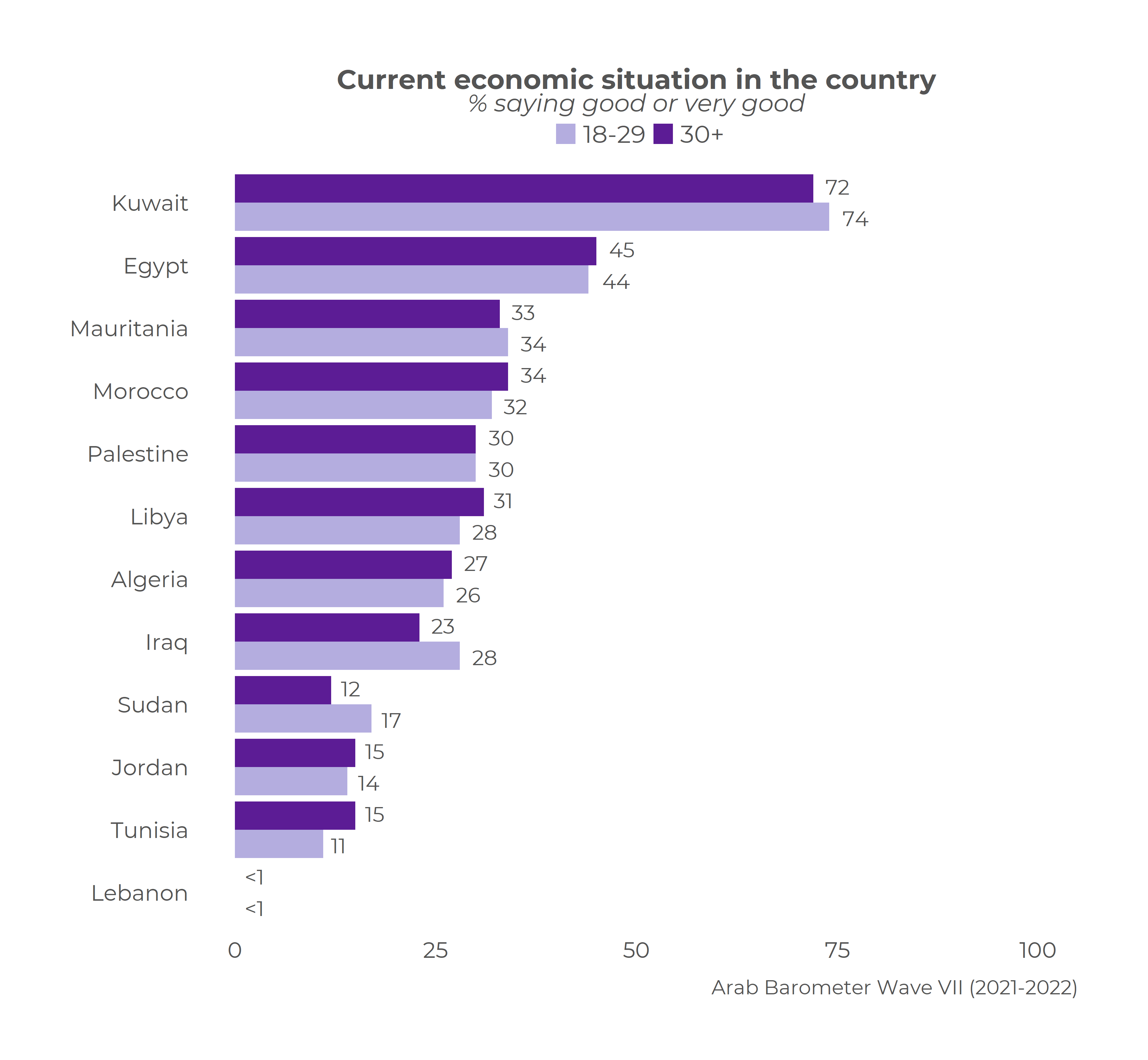

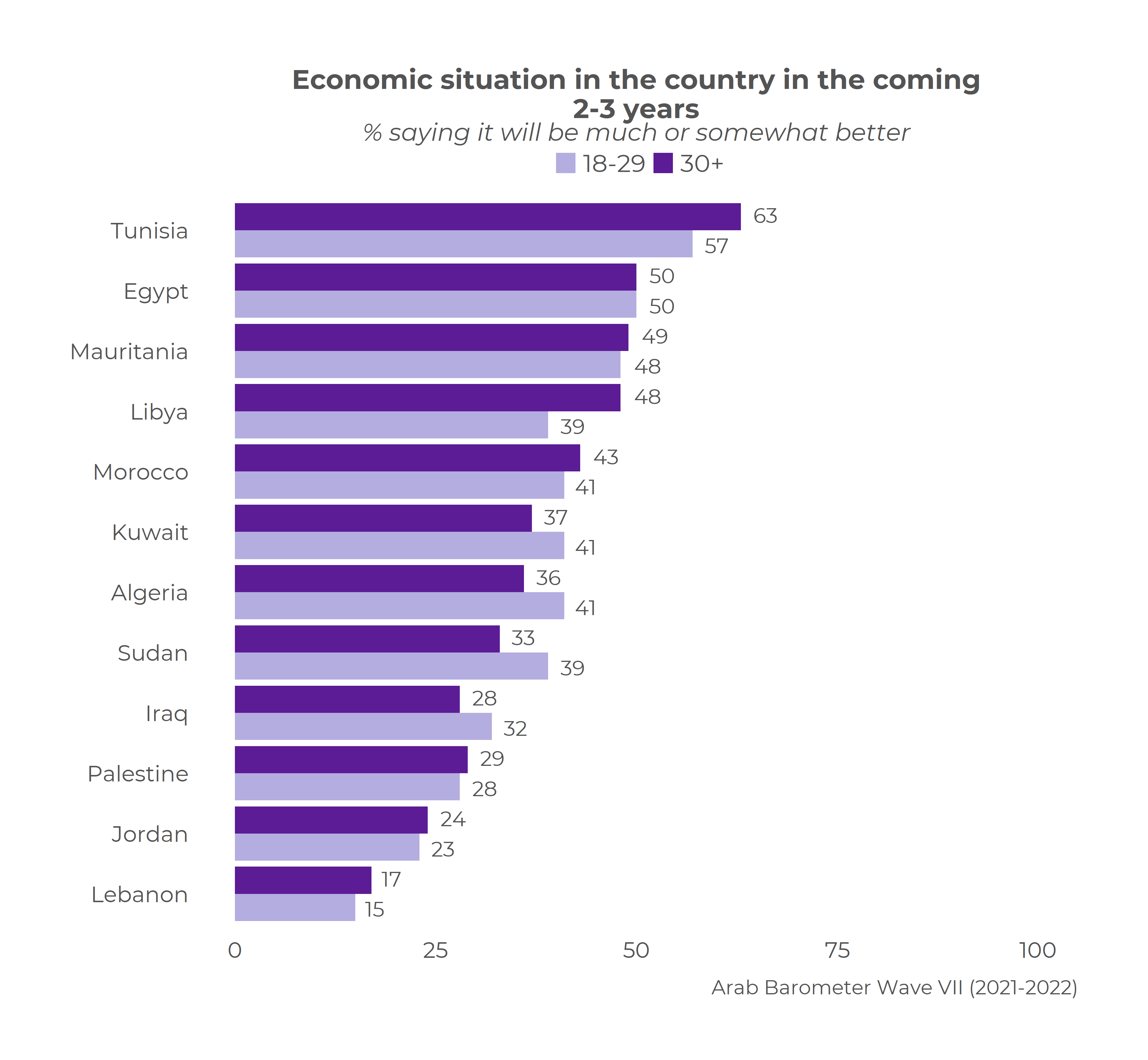

Findings from the Arab Barometer’s seventh wave (2021-2022) from 12 countries surveyed suggest that young people do not have unique outlooks towards the future with regards to quality of life and their countries’ economies compared to their older counterparts. There are no majorities in either age groups (youth: ages 18-29, older generations: 30+) that believe that their quality of lives are better than their parents’ except for two countries: Kuwait and Tunisia; majorities, however, are more positive in regards to expectations for the future of their children’s lives compared to their own. On the flipside, there are no majorities in either age group that say their countries’ current economic conditions are very good or good, nor do majorities say that it will get better in the next 2-3 years.

These results indicate that when it comes to future outlooks, MENA citizens’ opinions on their quality of life are not necessarily or exclusively driven by their perception of their countries’ economies. While citizens, and especially the youth, perceive the future quality of their children’s lives to get better, they do not perceive the future state of their country’s economies to improve. This calls for an exploration of other factors, country-specific and with a focus on gender, that may be at play for MENA citizens when considering future quality of life. The first of a two-part series on youth outlooks in the region, this blog delves into comparisons between young and old cohorts in the MENA region. The second part of this series will consider country-specific dynamics and probe, if not age, what other identity-related factors highlight important differences in the region.

Findings from the Arab Barometer’s seventh wave reveal that young people are not particularly unique in their beliefs and attitudes about their life quality and their countries’ economies compared to their older counterparts.

The majority of young people ages 18-29 only in Kuwait and Tunisia say that the quality of their lives are better than their parents, and the majority of young people in seven countries say that their children’s quality of life will be better than their own. But this is not different from citizens ages 30+. Only Kuwait has a significant majority of people aged 30+ that say their quality of life is better than their parents. Older age-groups in only three countries (Tunisia, Egypt, and Palestine) possess a majority that believes their children’s lives will be better than their own (with six countries at a statistically insignificant level). While young people are more positive about the future than older age cohorts, the trends remain similar between the age-groups.

Both youth and older generations of Lebanese citizens show the lowest rates of optimism. Only 20 percent of Lebanese youth say their quality of life is better than their parents, and only 16 percent of Lebanese aged 30+ share this sentiment. Lebanese youth also rank the lowest in optimism toward the quality of their children’s lives compared to theirs, although more optimistic than their current quality of life by +11 points (at 31 percent). Lebanese citizens ages 30+ are also slightly more optimistic about the quality of their children’s lives than their own. This overall departure from optimism in Lebanon aligns with literature on Lebanese perceptions and attitudes towards the future, expressing internal dissatisfaction and pessimism towards the future of Lebanon, their lives, and the financial quality of their lives.

The otherwise general increase in optimism towards future quality of life across both age groups is not matched by opinions about MENA countries’ economies and the future state of their economies. Kuwait is the only country where there is a majority that says the state of their country’s economy is good or very good (in both age groups). Additionally, in both age-groups, only Tunisia possesses a significant majority that believes that their country’s economy will get much or somewhat better in the next 2-3 years.

While Kuwaitis view their economy positively, contrary to the rest of the region, they are less convinced it will get better. A majority of Kuwaitis also think quality of life is good and will be better for their children. While Kuwait has been one of the region’s remittance-generating countries with relative economic stability, future prospects appear to show economic growth to be slowing down. This is similarly depicted in these results, as the majority of Kuwaitis are significantly positive about the current state of the economy, and sentiments about the future are not sustained positively.

Majority of Tunisians, across both questions, express positive trends within both age groups, and especially with regard to the future. A majority of Tunisian youth say their quality of lives are better and their children’s lives will be better, and a majority of Tunisians ages 30+ say the quality of their children’s lives will be better. Additionally, the majority of Tunisians from both age groups only say that their country’s economy will be better in the next 2-3 years. Although waning today, Tunisians showed optimism and support for Kais Saied’s presidency and campaign as he came into power in 2019, which may have played a role in inspiring the optimism expressed in the Arab Barometer surveys conducted in 2021-2022. With his promises to curb corruption, he has gained support and a potential spark in optimism, especially toward Tunisia’s economy. These results, however, cannot be conflated to speak to current attitudes towards governance in Tunisia, as optimism has depleted among the population and toward Saied.

These results primarily highlight two takeaways: that MENA youth, at first glance, are not different in perceptions compared to the older age groups; and that MENA citizens’ perceptions about the quality of their lives are not exclusively tied to their perceptions about their countries’ economies, as MENA citizens are more positive about the future of life quality than they are about the future of the economy. Where many sources have attempted to directly correlate economic growth with citizens’ happiness, this piece offers the possibility that there is more that contributes to perceptions on one’s well-being, particularly in the MENA region, that are not directly linked and dependent on the economy.

This begs the question of what is worth considering to understand the youth’s perceptions of life quality. While this piece establishes largely uniform sentiments on life quality and economy across both youth and those ages 30+, the following post will explore a gendered piece as well as country-specific dynamics that help in conveying unique patterns in youth sentiments.