On March 20, 2003, U.S. forces invaded Iraq and toppled the regime of Saddam Hussein. The U.S. then set about a political transformation of Iraq with the stated goal of bringing about democracy, including instilling a parliamentary system with regular elections. Since that time, Iraq has suffered significant turmoil, including an armed resistance against the U.S., civil conflict, and the eventual takeover of large swaths of the country by the Islamic State. Today, Iraq remains deeply divided. The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) operates largely autonomously from the remainder of the country while the parliament in Baghdad remains disunified, only forming a government a full year after the October 2021 elections.

Twenty years after the invasion, Arab Barometer provides insight into the extent to which support for democracy has or has not taken root in the country. The results make clear that while Iraqis remained very committed to the idea of democracy up until the early 2010s, doubts about this system have increased significantly in the years after 2013. Now, although a majority of Iraqis continue to favor democracy, they are among the most skeptical populations across MENA about this system of governance.

Commitment to democracy

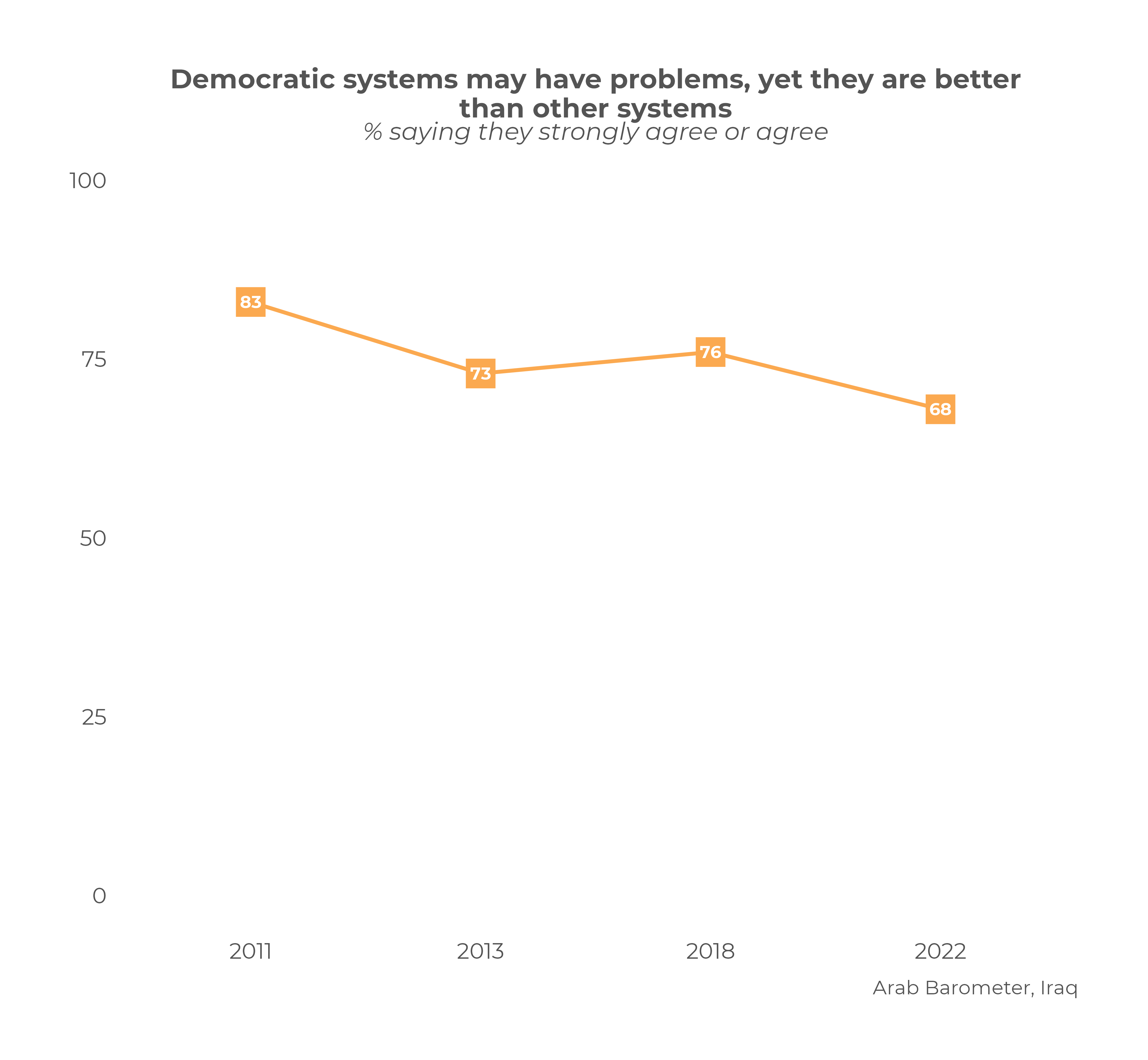

Overall, two-thirds (68 percent) of Iraqis still affirm that despite its problems, democracy remains the best system of governance. However, this belief has fallen by 15 points since 2011 when it stood at 83 percent. Additionally, this level is among the lowest found across the twelve countries surveyed in MENA in Arab Barometer Wave 7 (2021-2022), with only Egypt (65 percent) and Morocco (54 percent) exhibiting lower levels of support for democracy.

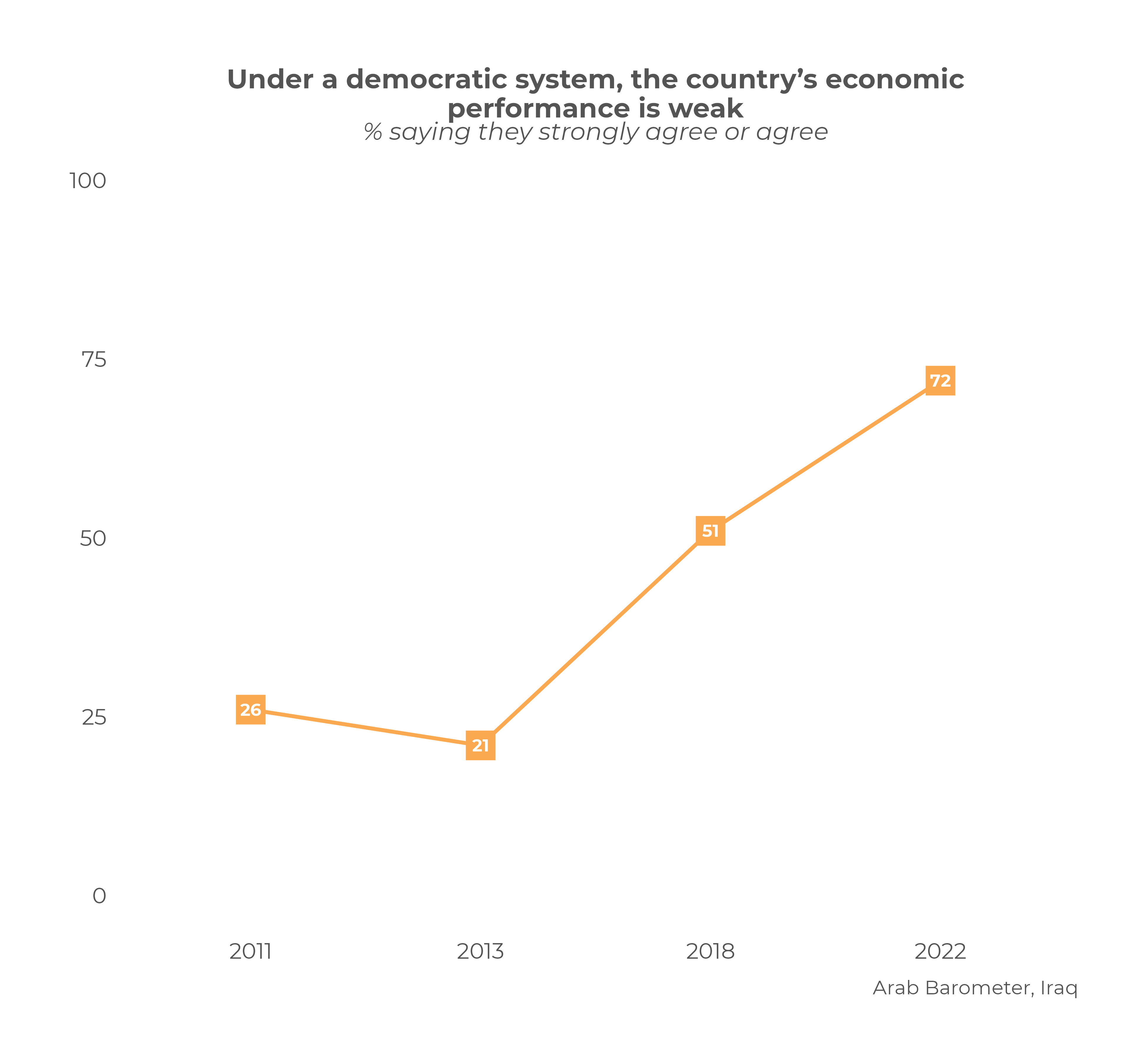

The main reason for this drop appears to be growing doubts in the benefits associated with democracy. In 2011, just a quarter (26 percent) of Iraqis said that economic performance was weak under a democratic system. In 2013, this percentage was only 21 percent. However, this level jumped to half of citizens (51 percent) in 2018 and then 72 percent in 2022.

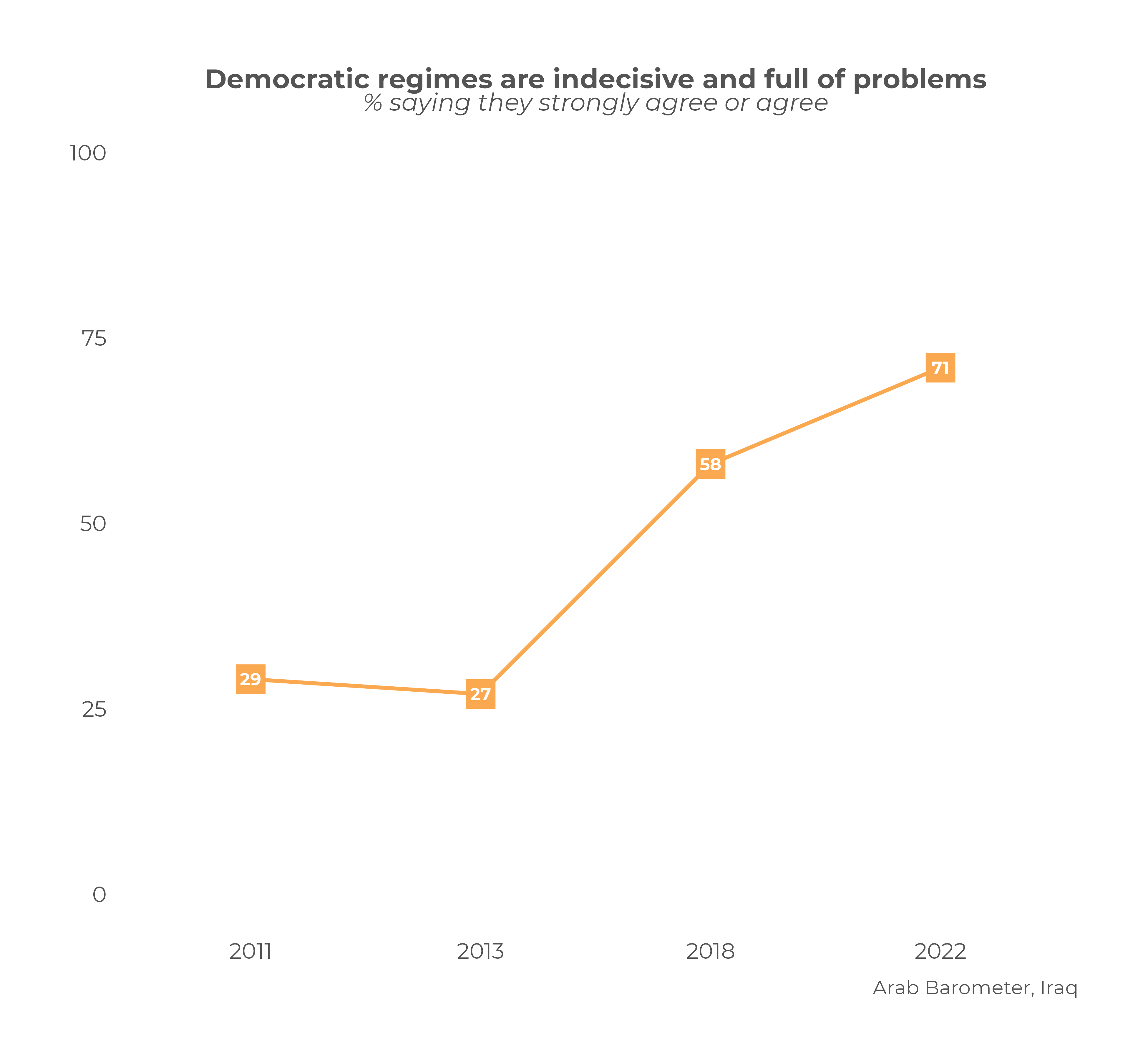

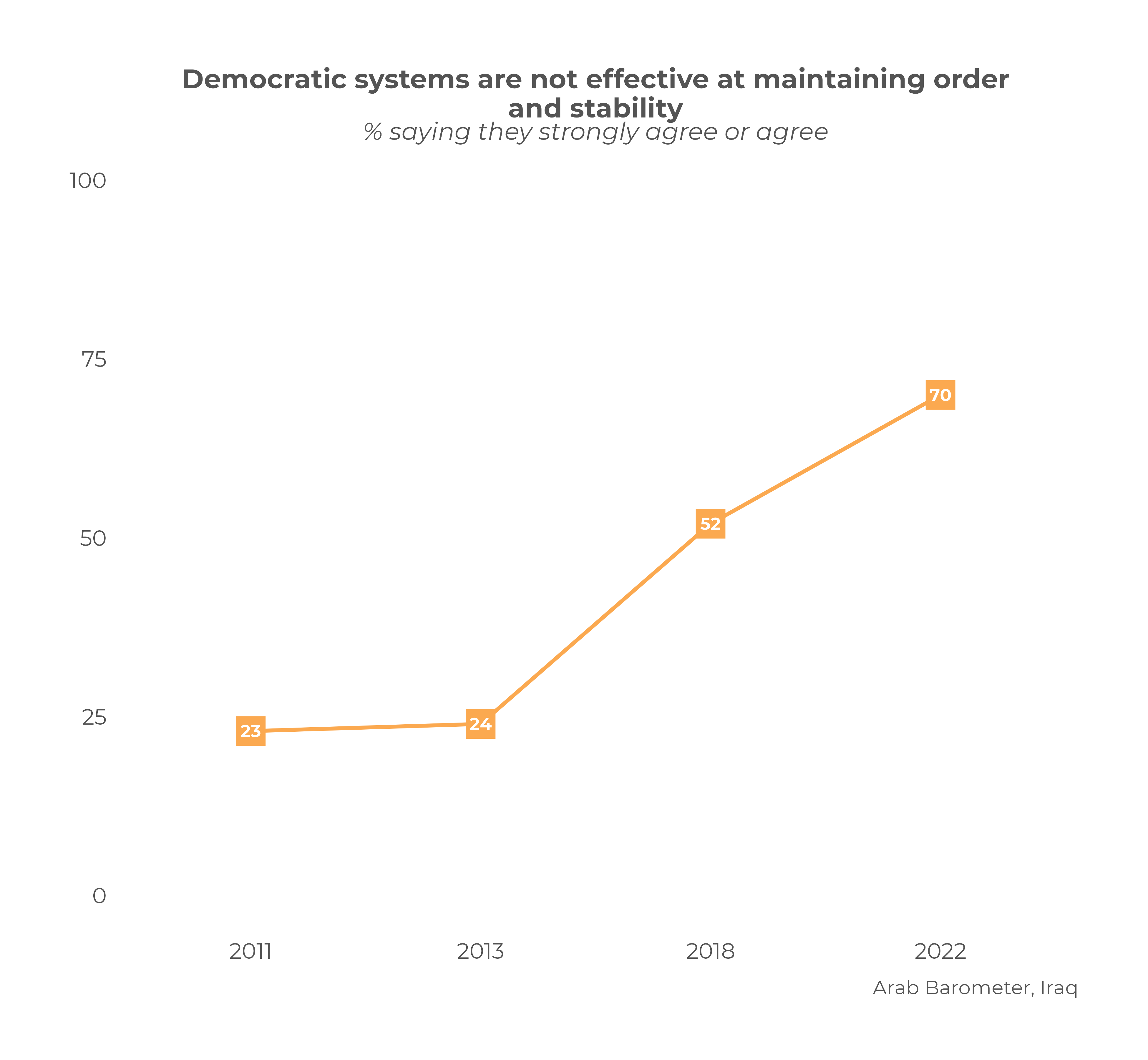

The results are similar for other concerns that are sometimes associated with democracy. When asked if democracies are indecisive and full of problems, about three-in-ten agreed in 2011 (29 percent) and 2013 (27 percent). By 2018, this level had doubled to 58 percent with a further rise of 13 points to 71 percent in 2022. The same trend is also found for the belief that democratic systems are no effective at maintaining stability, rising from 23 percent in 2011 to 70 percent in 2022.

Failings of the political system

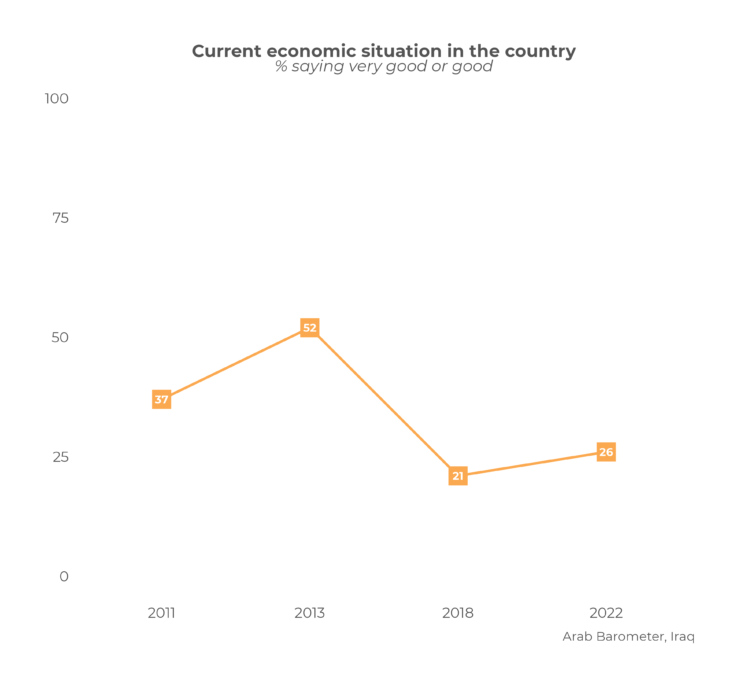

Iraqis’ growing concerns about democracy closely track with developments in their country over this period. Ratings of economic performance have declined since 2013, which was also the low water mark for concerns about potential problems associated with democracy. At that time, when oil prices were at near record highs, about half (52 percent) of Iraqis rated the economy as good or very good. In 2018 just 21 percent said the same compared with 26 percent in 2022.

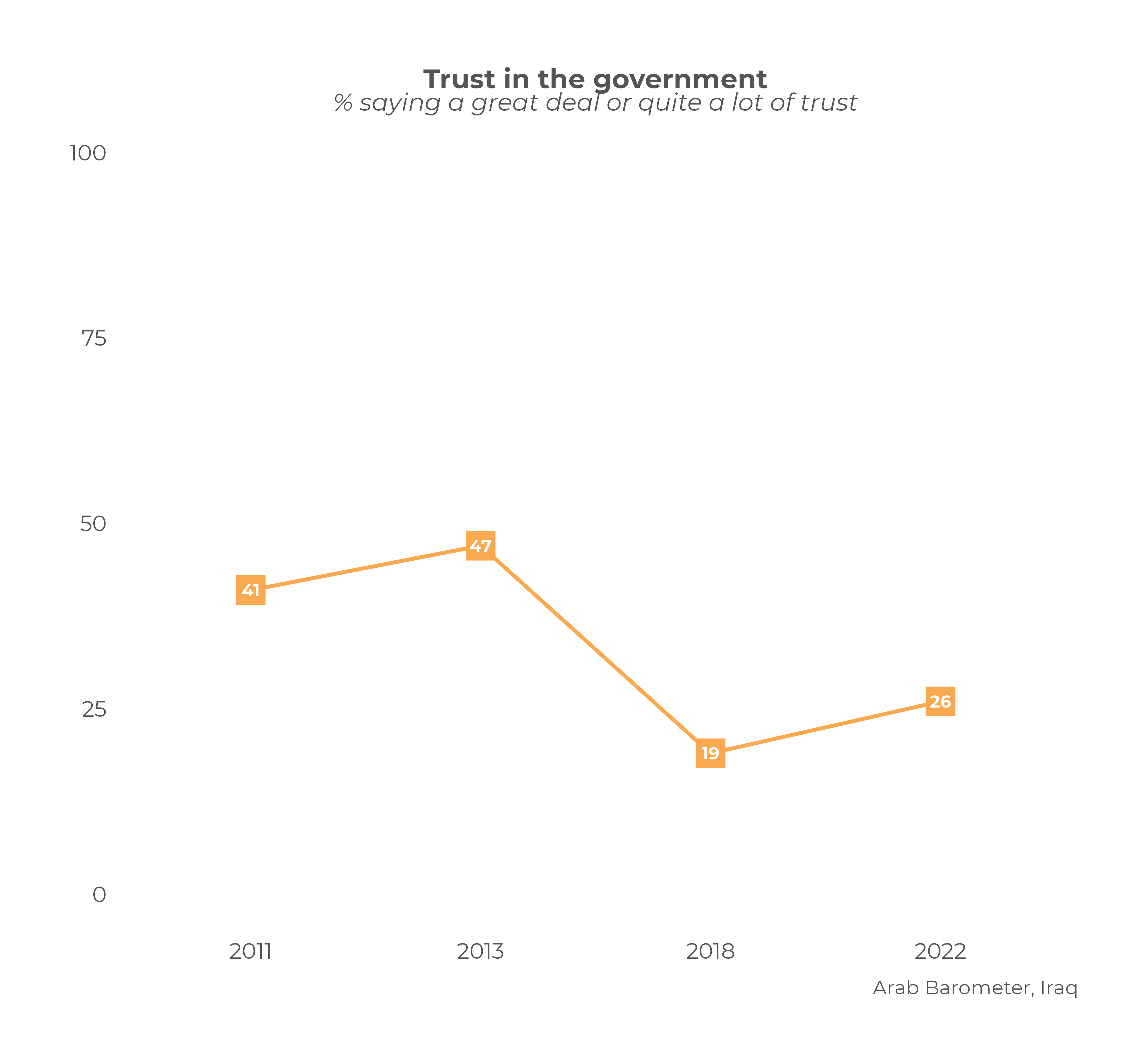

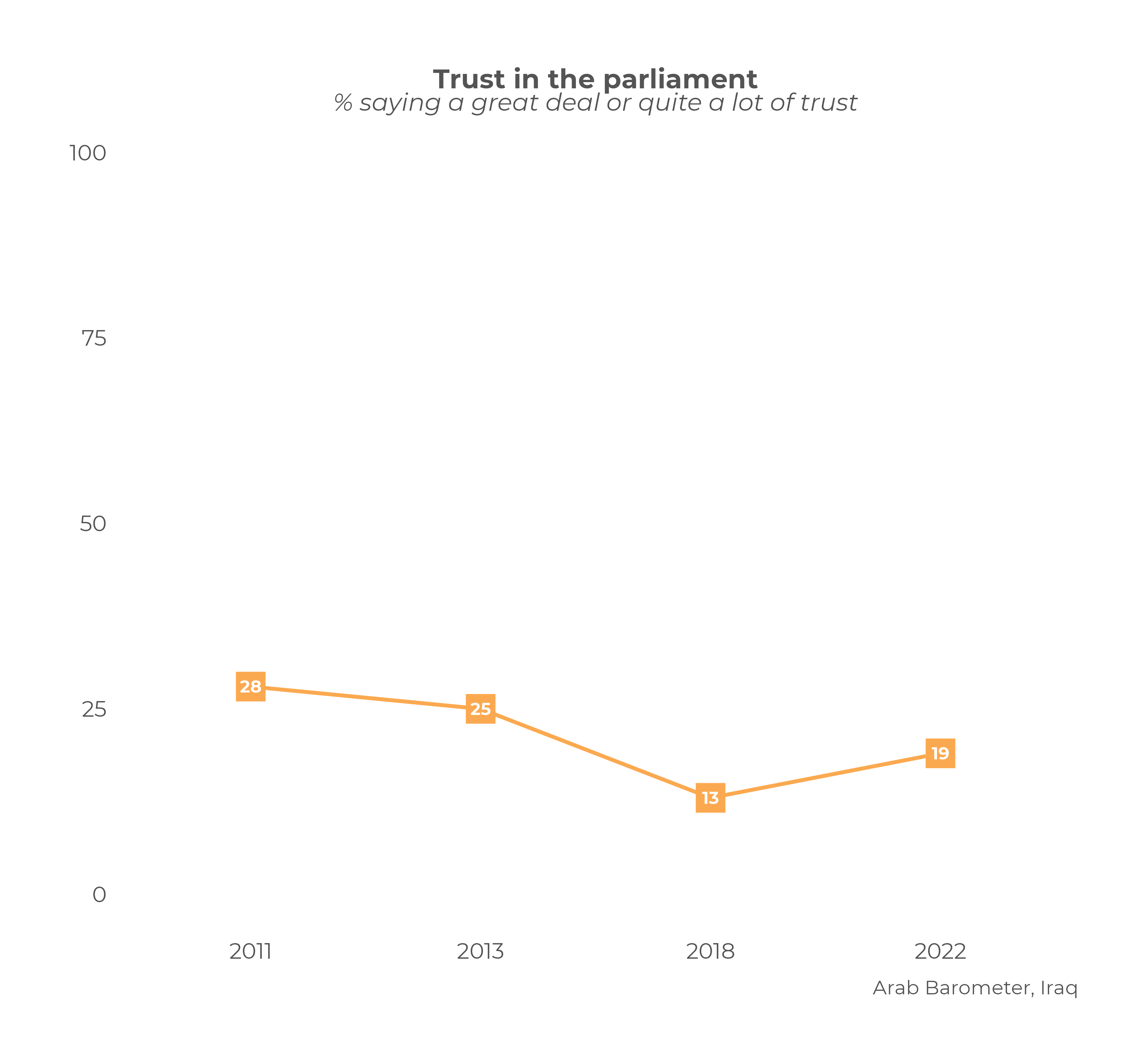

Meanwhile, levels of trust in the government have fallen dramatically since the early 2010s. In 2013, almost half (47 percent) of Iraqis had confidence in the government, which is nearly twice the percentage as in 2022 (26 percent). Meanwhile, trust in parliament has been consistently low, with fewer than three-in-ten exhibiting confidence in this body since 2011. By comparison, the legal system (40 percent) and local government (33 percent) currently fair somewhat better in the eyes of Iraqis, but still only a minority of citizens have confidence in either.

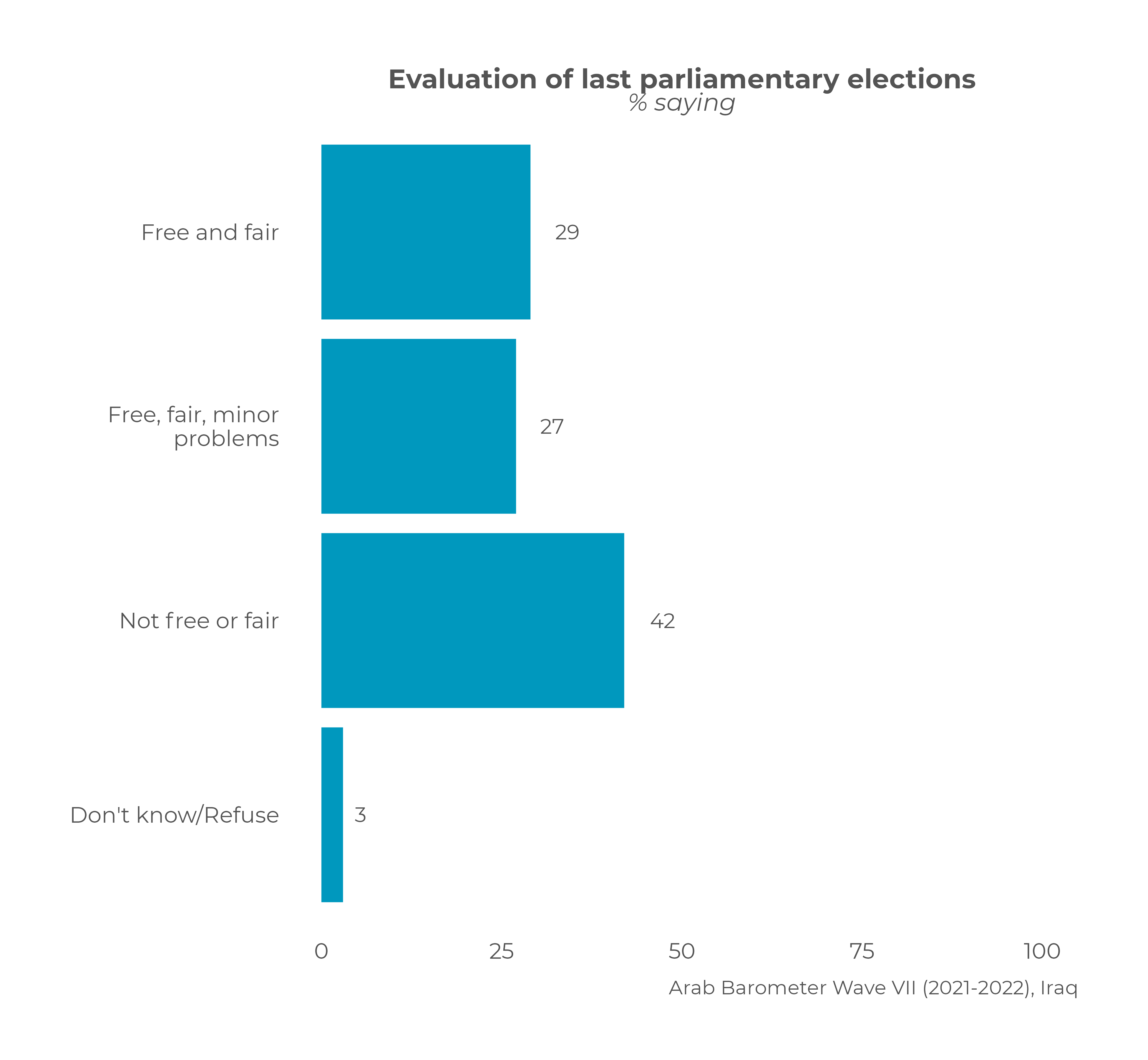

A key issue that hurts the legitimacy of the government is the fact that even though regular elections are taking place, few in the country believe elections are fully free and fair. In fact, the plurality say they are not free and fair (42 percent) while a further 27 percent say they are largely free and fair but have minor problems. Only three-in-ten (29 percent) believe that the October 2021 parliamentary elections were entirely free and fair.

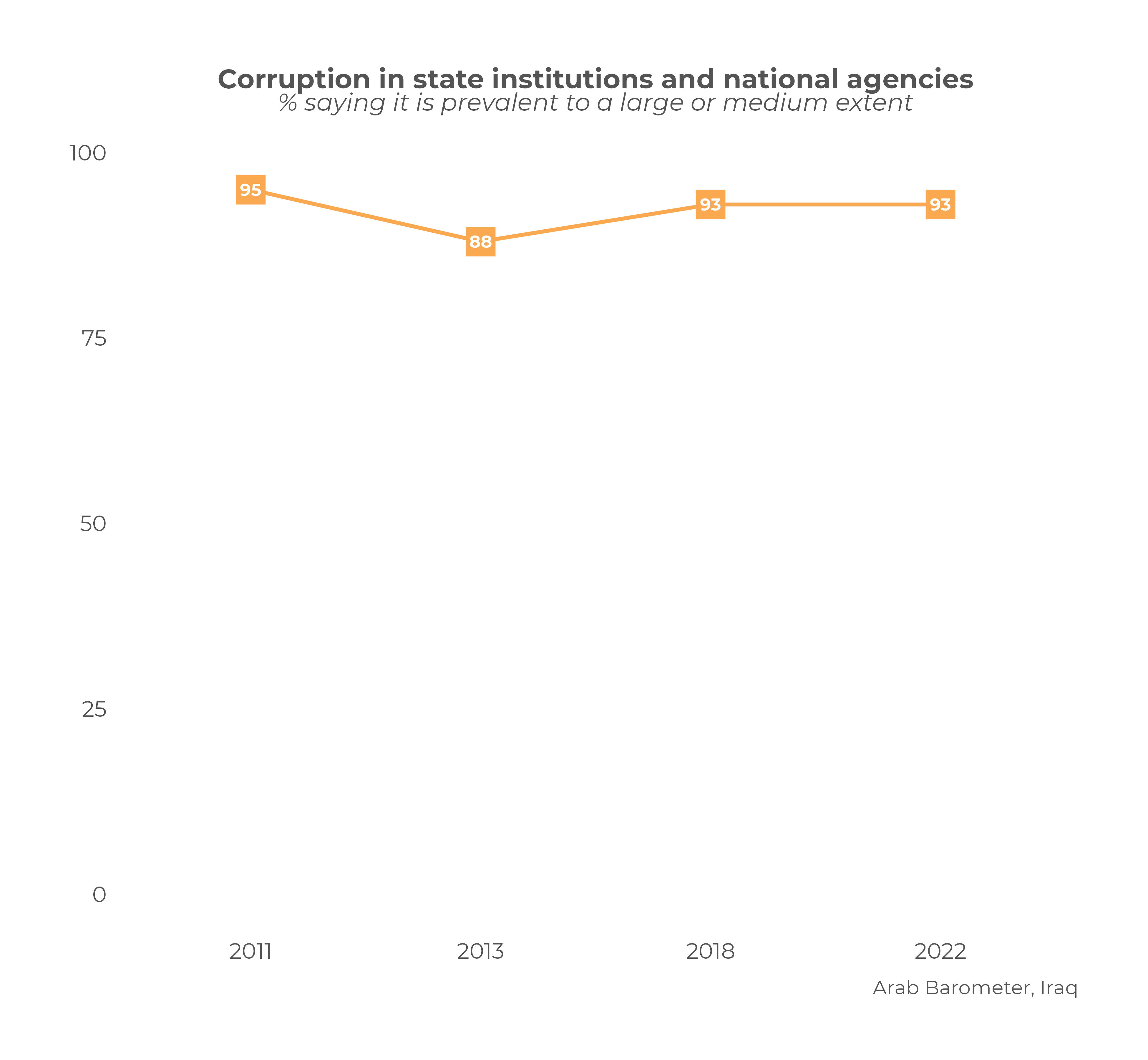

Another challenge undermining confidence in public institutions is corruption. Nine-in-ten Iraqis say that there is corruption to a great or medium extent in state institutions, which is essentially unchanged since 2011. Today, this level is among the highest in the ten MENA countries for which data are available. Moreover, a quarter (26 percent) of Iraqis say that corruption is the most important challenge facing the country, which is a greater percentage than for the economic situation, foreign interference, or instability. Among all countries surveyed across the region in 2021-2022, only in one other does corruption rank ahead of all other challenges, underscoring the degree to which this ongoing scourge plagues Iraq.

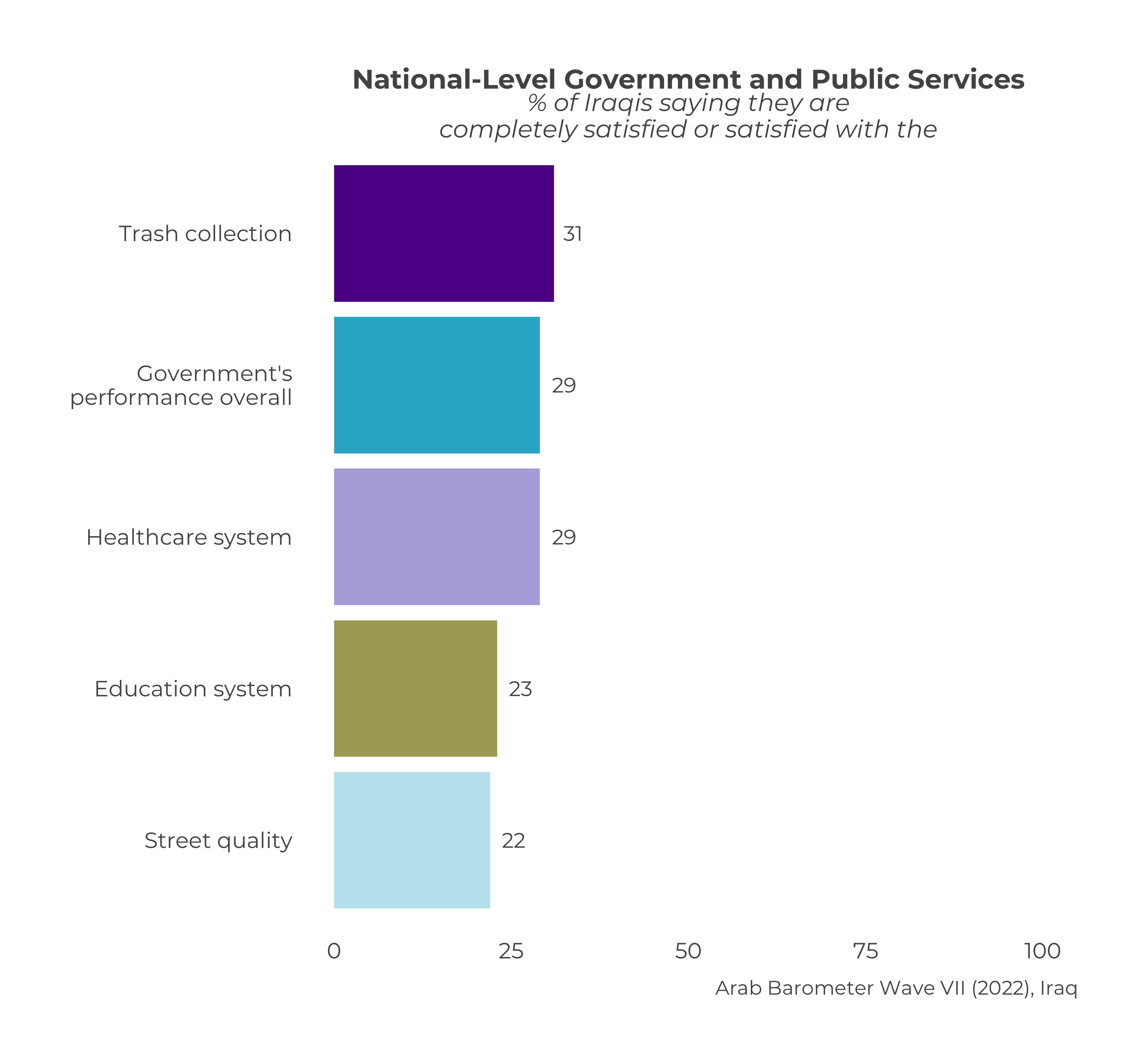

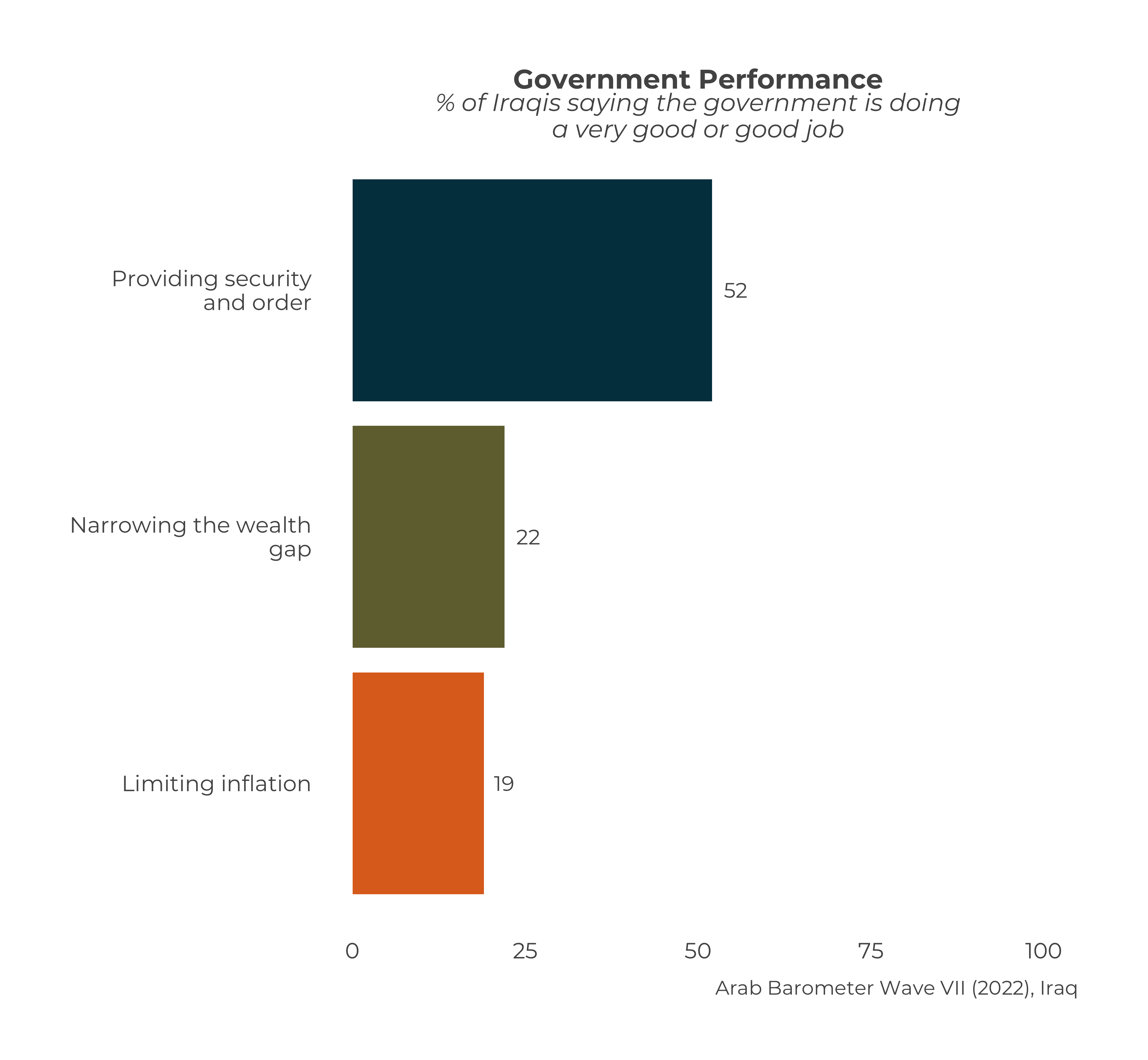

Compounding these challenges is the failure of government institutions to provide citizens with quality services. Fewer than one-in-three Iraqis are satisfied or completely satisfied with basic services such as trash collection (31 percent), the healthcare system (29 percent), the education system (23 percent), and the quality of the country’s streets (22 percent). Ratings of the government’s performance on narrowing the wealth gap (22 percent) and limiting inflation (19 percent) are similar.

What do Iraqis want from their political system?

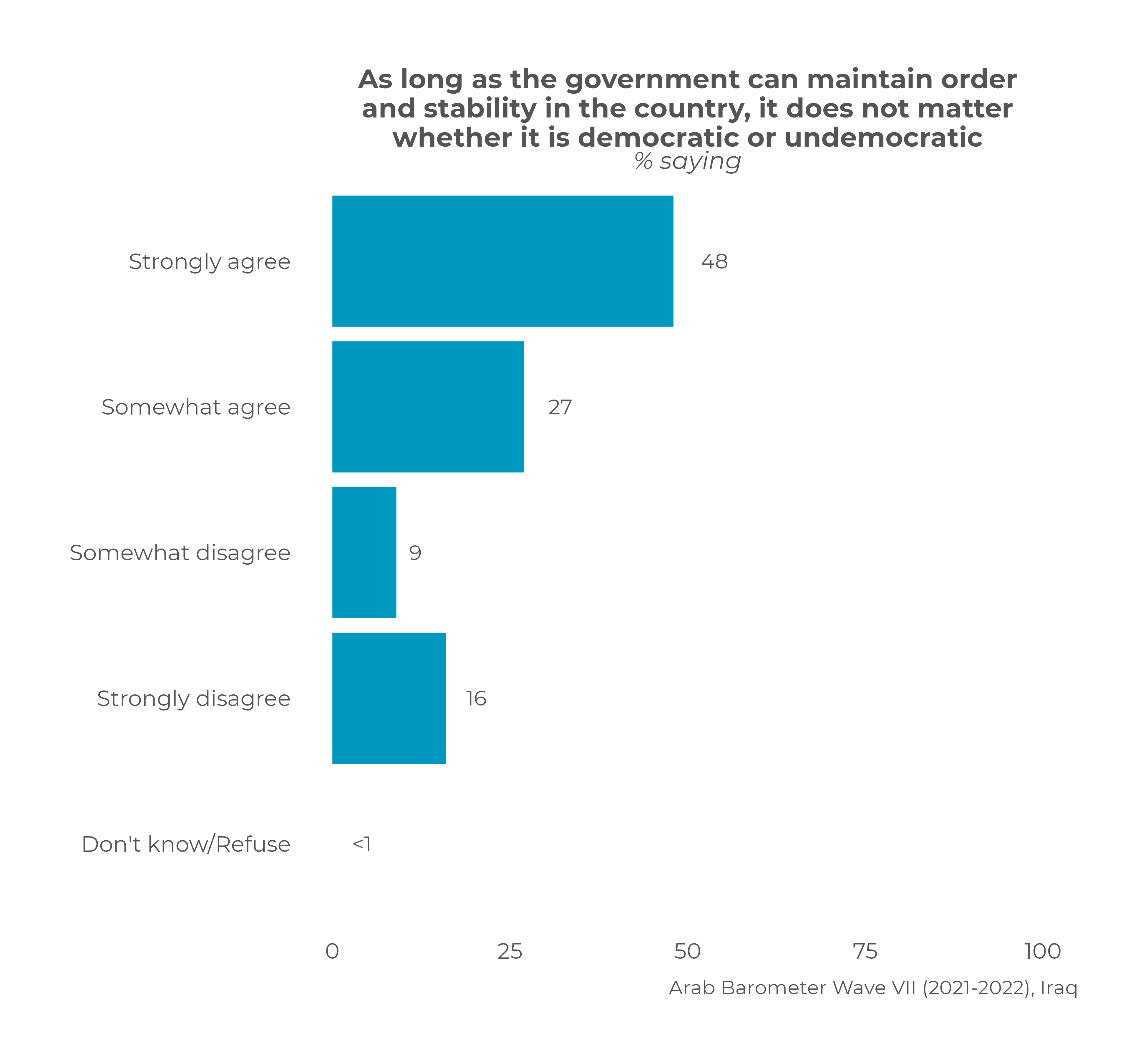

Twenty years after the fall of the regime of Saddam Hussein, Iraqis are looking for a robust political system that yields results. Although they affirm that democracy is the best type of system, clear majorities would be willing to accept an alternative system of governance if it would produce outcomes that improve their current situation. For example, three-quarters say that it does not matter if the country is democratic or undemocratic so long as the government can maintain stability. Among all countries surveyed, this percentage is joint highest with Libya, which is a country experiencing a civil conflict.

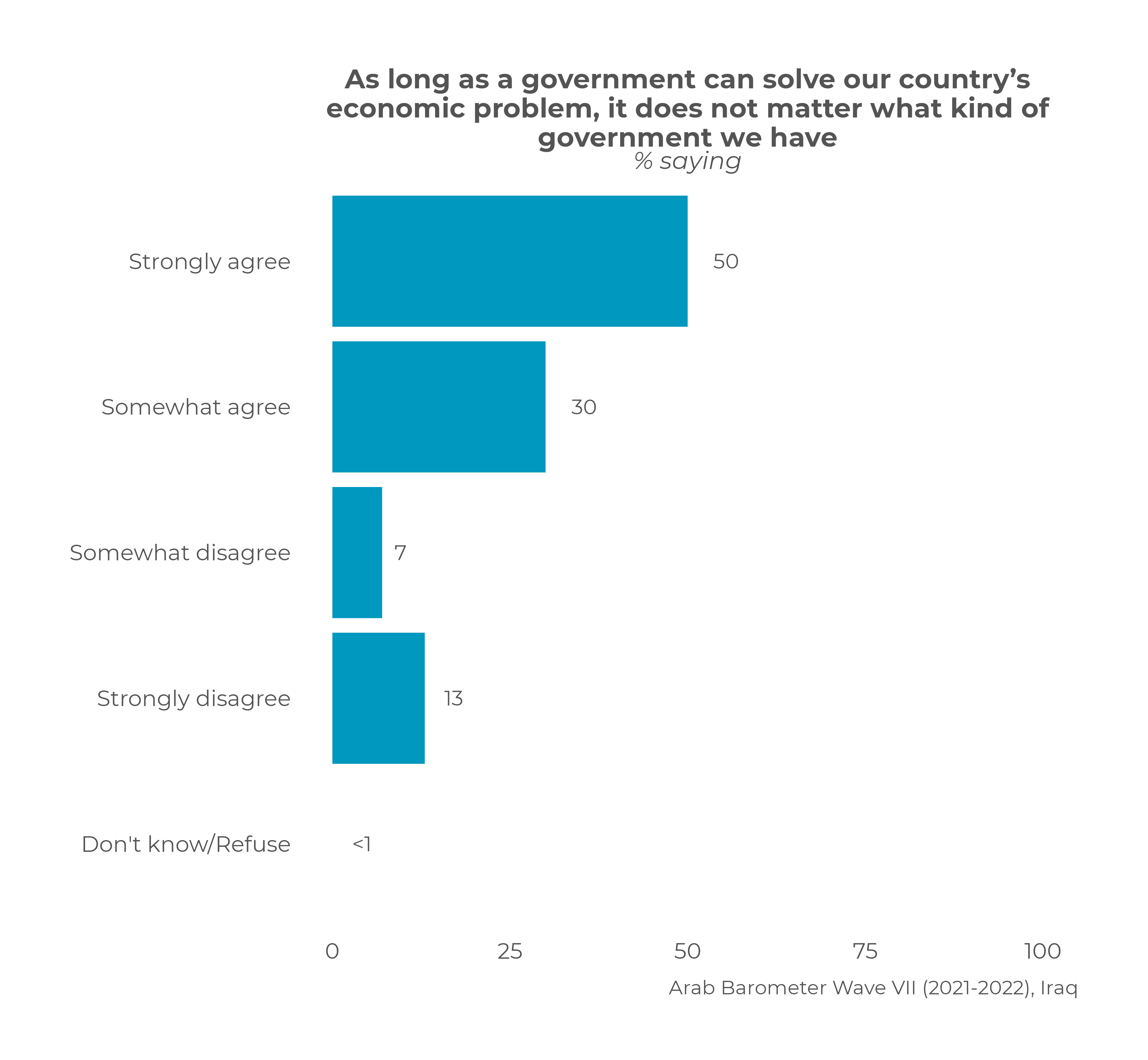

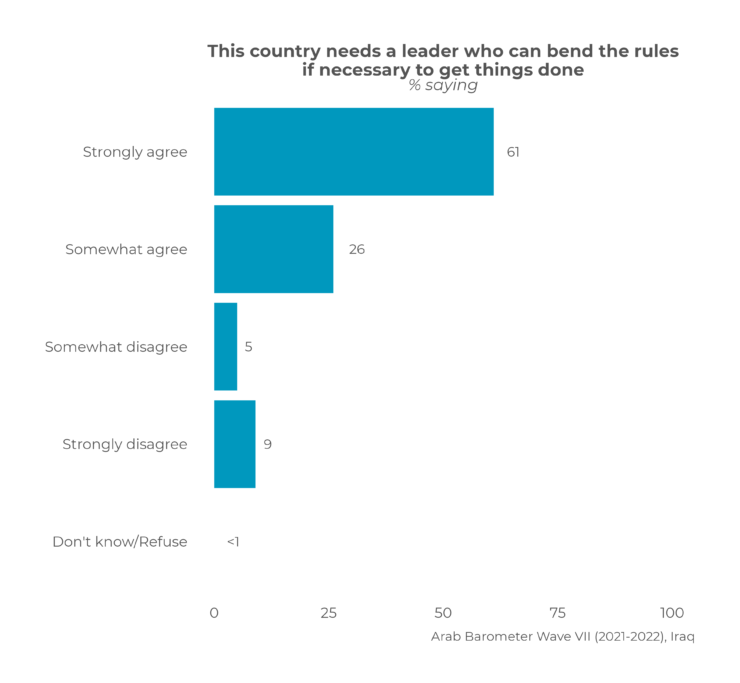

When asked if they agree with the statement that as long as the government can solve the economic problems, it does not matter what kind of government it is, eight-in-ten (79 percent) Iraqis agree. This level is again the highest in the MENA countries surveyed, ranking slightly above the percentage in Tunisia and Libya. Finally, when asked if the country needs a leader who can bend the rules if necessary to get things done, nearly nine-in-ten Iraqis agree, which is greater than in any other country included in the survey.

After years of civil unrest, Iraqis continue to believe that there is no better system than democracy but are also tired of waiting for the political system created in 2005 to deliver results. Frustrations about the economy, the inability of the government to ensure stability, rampant corruption, and the poor state of public services have taken their toll. Elections have not resulted in governments that have been able to address these root problems, or at least not for all the country’s citizens. As a result, citizens are losing faith in this political system and appear to be blaming democracy for some of these failures, including the poor economic and security situation in the country.

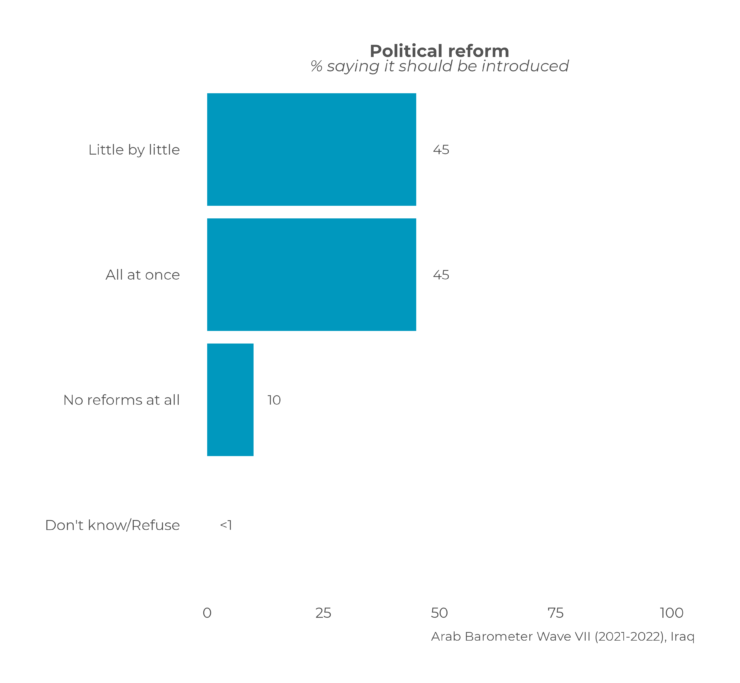

Stemming the tide would require significant changes. Nearly half (45 percent) of Iraqis favor major political reforms to be introduced immediately while another 45 percent want reforms to be introduced more gradually. Combined, that means that nearly all citizens agree that reform is needed. If the political system delivered meaningful improvements to the lives of citizens, it is likely that faith in democracy as a system of government would be rebuilt. If such changes do not take place, it becomes increasingly likely that support for democracy will continue to decline in the years ahead.