Nearly 19 years have passed since the removal of Saddam Hussein from power and the establishment of the second republic of Iraq. While the structures of the State and the political system have been deeply and extensively reshaped, the impact of this transformation on the life of Iraqis remains debated. The latest Arab Barometer’s (AB) survey (Wave VI which was– conducted between March and April of 2021) attempts to contribute to this debate. The findings of this survey display public discontent over political life, dissatisfaction with education and health systems and economic performances, and concerns about civil liberties.

In October 2019, the cabinet of then-Prime Minister Adel Abdul al-Mahdi faced a major wave of popular protests in Baghdad which rapidly spread to other Iraqi urban centers. Demands revolved around socio-economic reforms and the end of the corrupt and sectarian political system. The brutality of the response brought by the police and militias changed the protesters’ attitude to demanding political reforms and a new social contract for the Iraqi state. Al-Mahdi submitted his resignation on the 1st of December 2019 and in May 2020, the Council of Representatives (CoR) asked former intelligence chief, Mustafa al-Kadhimi, to form a provisional government. Al-Kadhimi was able, to some extent, to intensify the fight against corruption and meet some of the popular demands. He strengthened the anti-corruption policies and established a special committee to investigate allegations of corruption and unusual crimes, with the help of the Commission of Integrity. Genuine improvements as a result of these measures may not be obvious right away.

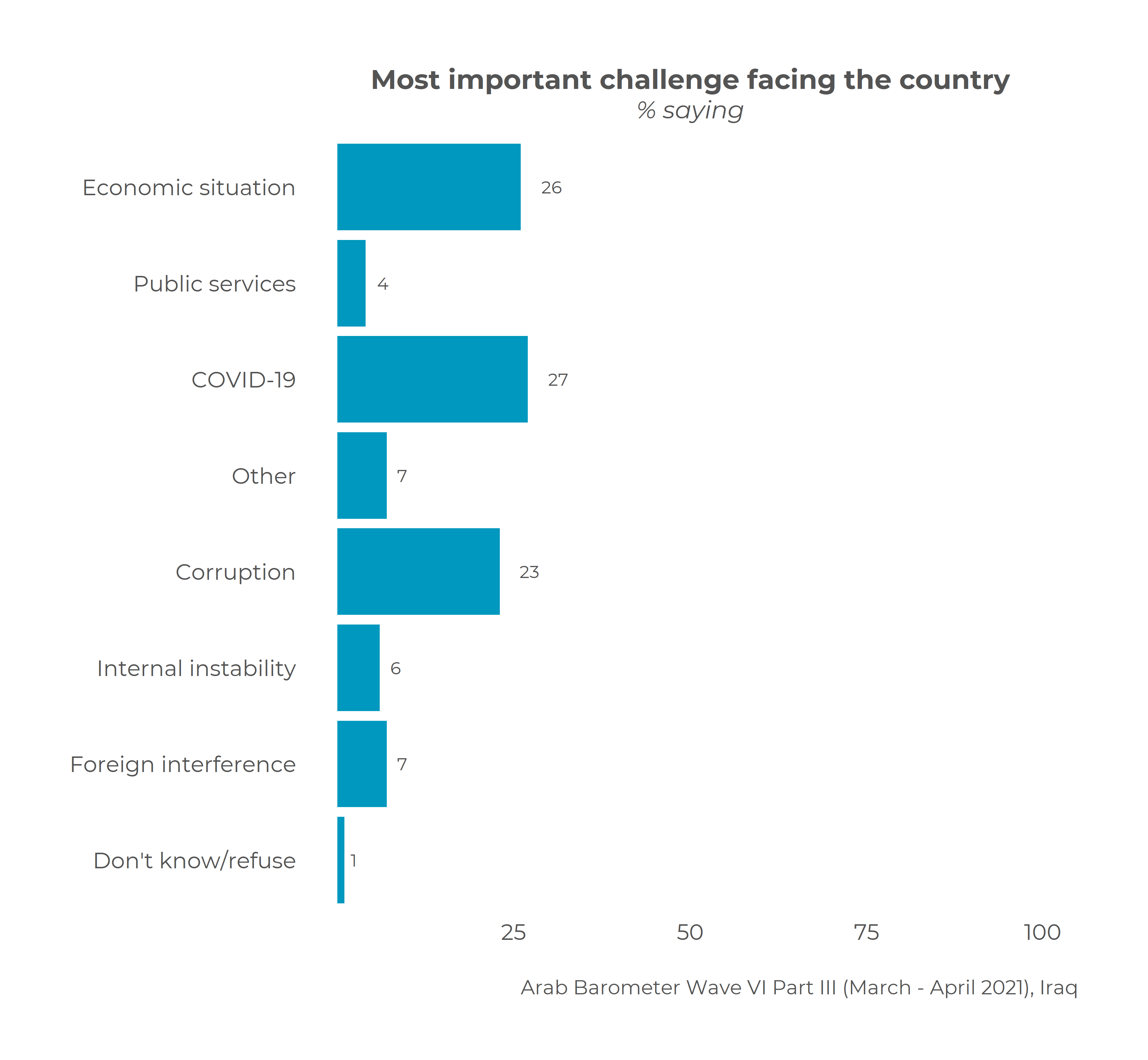

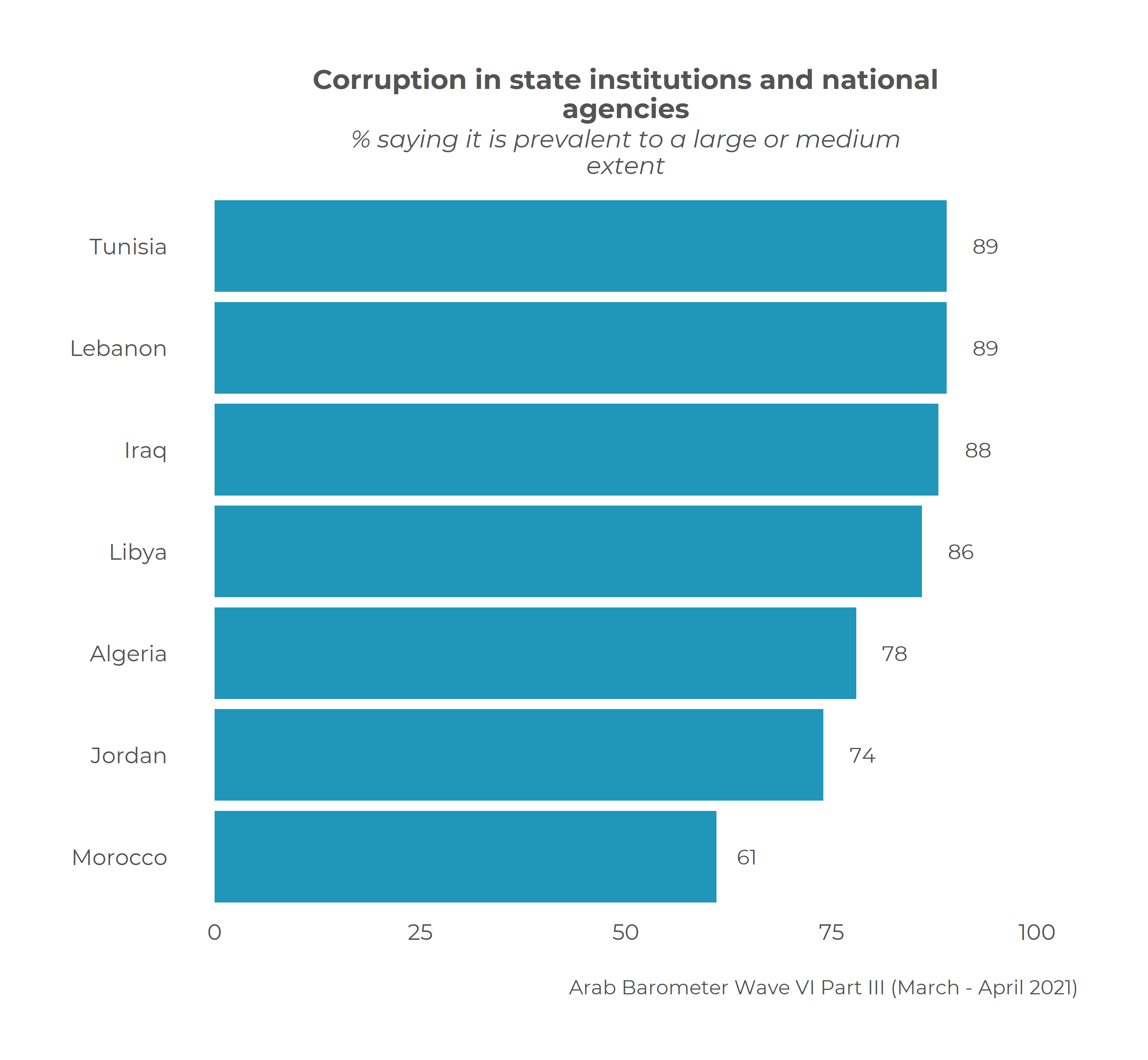

The public views corruption as one of the main challenges that hinder progress in the country. Nearly a quarter (23%) of Iraqis say that corruption is the most important challenge facing their country; the highest of all countries included in the AB spring 2021 survey. The widespread corruption is a source of agreement in the country, with 88% of Iraqis saying it is prevalent to a large of medium extent in state institutions and national agencies. The country had general elections in October 2021, but no government has been formed yet, causing a major political vacuum.

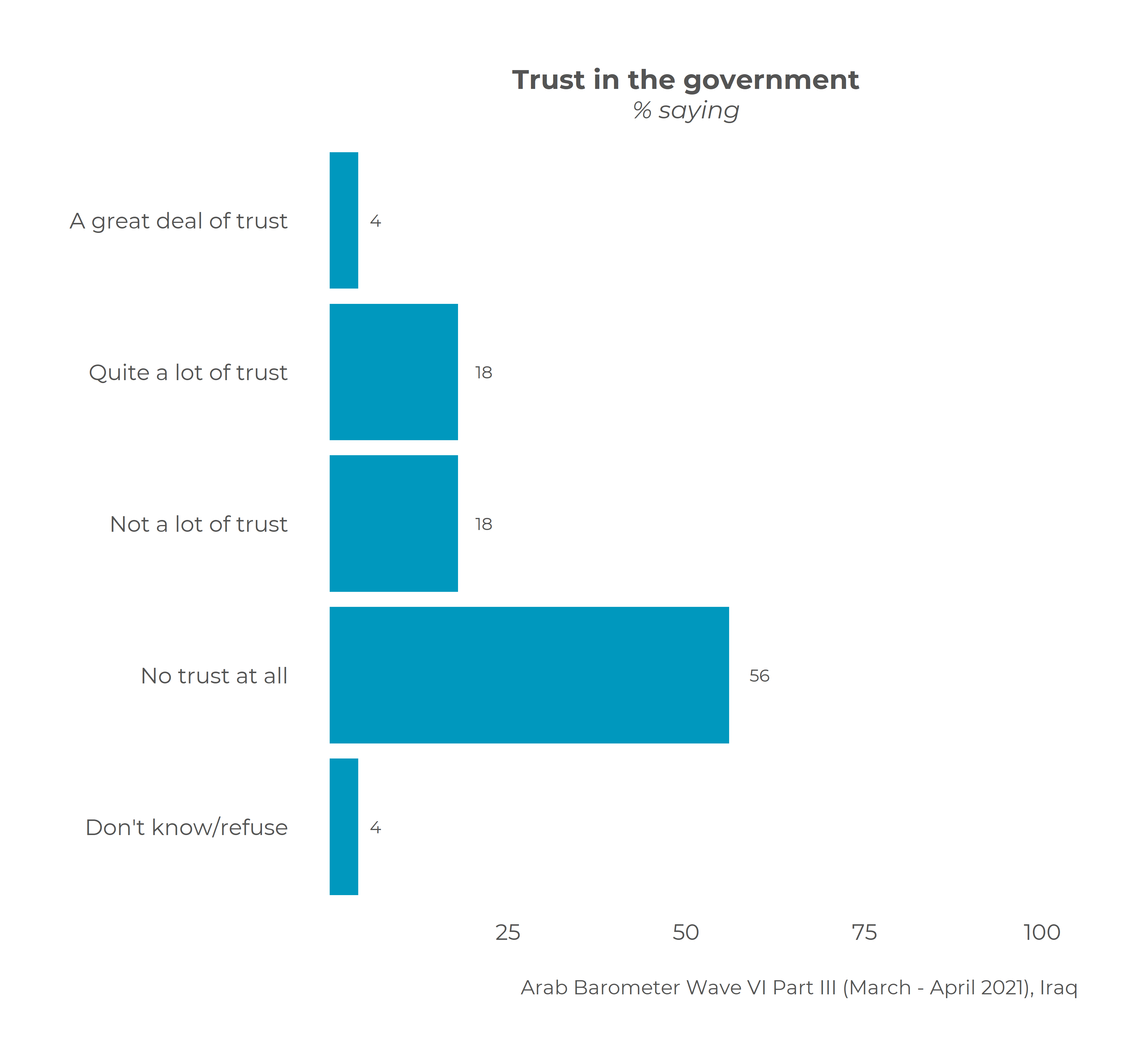

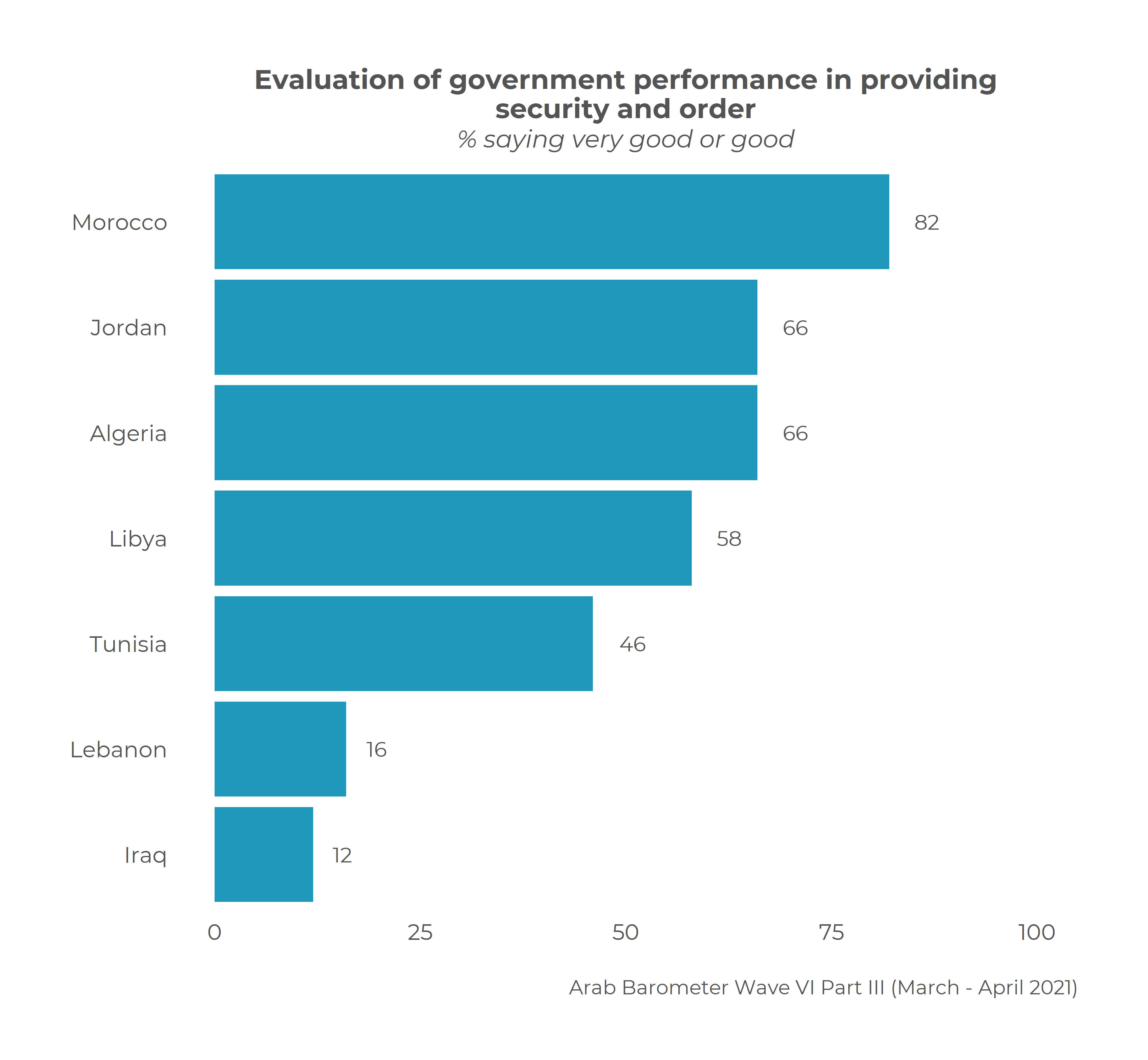

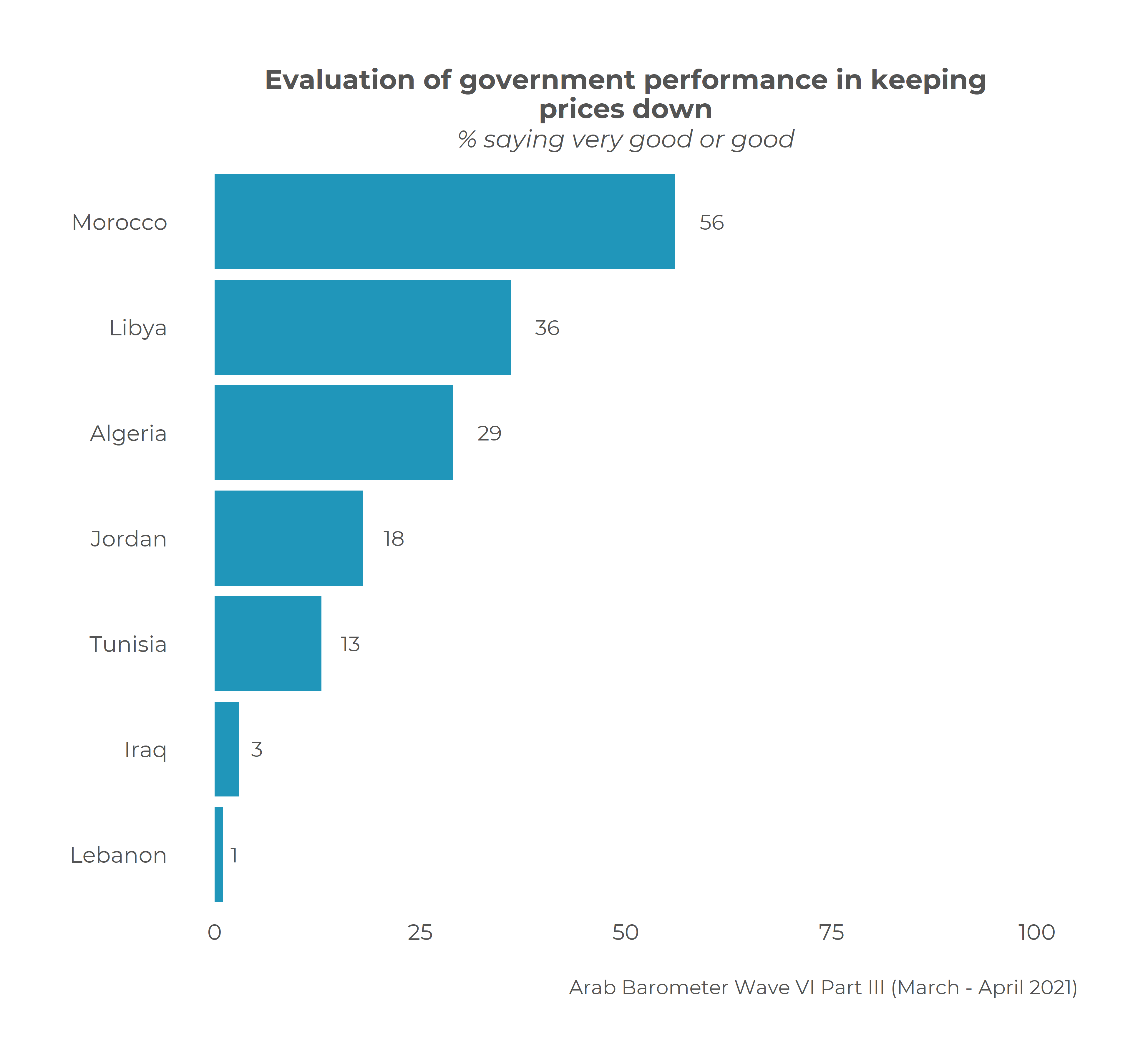

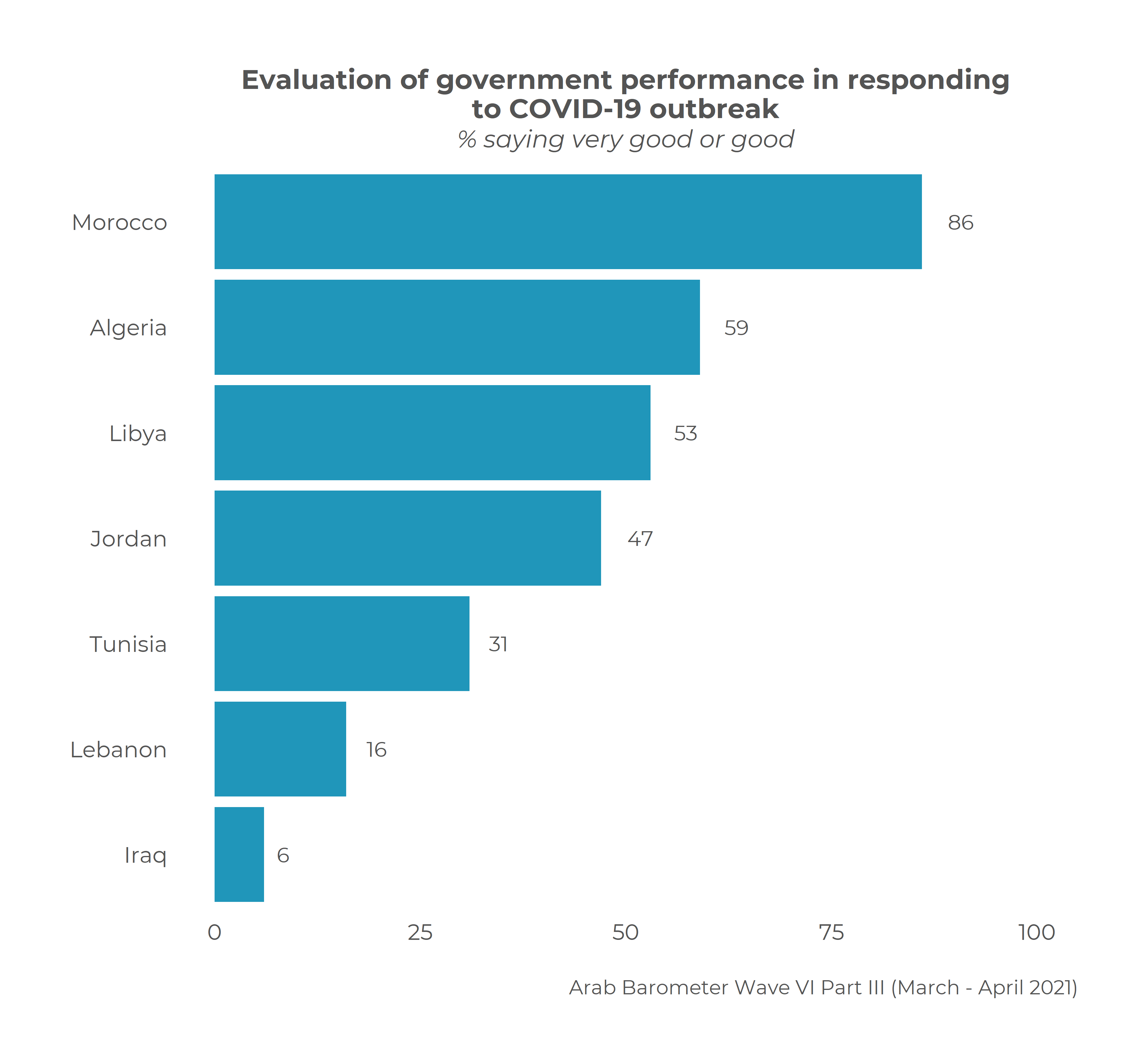

Trust in state institutions is low. When AB conducted the sixth wave survey in Iraq (March 2021), al-Kadhimi’s provisional government was already facing multiple challenges, including the Covid-19 pandemic, the need to address the demands of protesters, and the preparation for legislative elections. Around a fifth of Iraqis (22%) express their trust in the government, while more than half of the population (56%) say they have no trust at all in it. As for performance, the Iraqi government ranked among the lowest in the AB survey for providing security and order (12% – lowest), controlling inflation (3% – second lowest), and combating COVID-19 (6% – lowest)

Trust in the legal system is also low. The Federal Supreme Court (FSC) – which is the highest judicial body in Iraq and notably tasked to interpret and enforce the constitution – has never been approved by CoR. The establishment of the Court, required in Article 92-2 of the 2005 constitution, must be vetted by a two-thirds resolution by CoR. However, the Court was formed by the provisional government of Ayad Allawi (2004-2005). Therefore, there is an argument that the FSC was not established in accordance with the rule of law and its decisions are often a source of contestation, especially between the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and the Federal Government (FG). KRG views the Court as unconstitutional and is reluctant to implement its verdicts. KRG-FG relations are based on closed-door consensuses instead. For instance, in February 2022, FSC declared that a 2007 oil and gas law of Iraq’s Kurdistan Region (KRI) is unconstitutional. The decision sparked a political dispute between the FG and KRG with the latter declaring that FSC is unconstitutional. Finally, there are constant criticisms of the Court’s political neutrality, especially when it comes to ruling on questions that involve high political profiles.

The Central Criminal Court has not been able to resolve major corruption and fraud cases. It has violated basic fair trial criteria of Islamic State-related cases. In January 2020, the UN Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI) concluded that the Court’s hearings are “ineffective legal representation,” and lack “adequate time and facilities to prepare a case”.

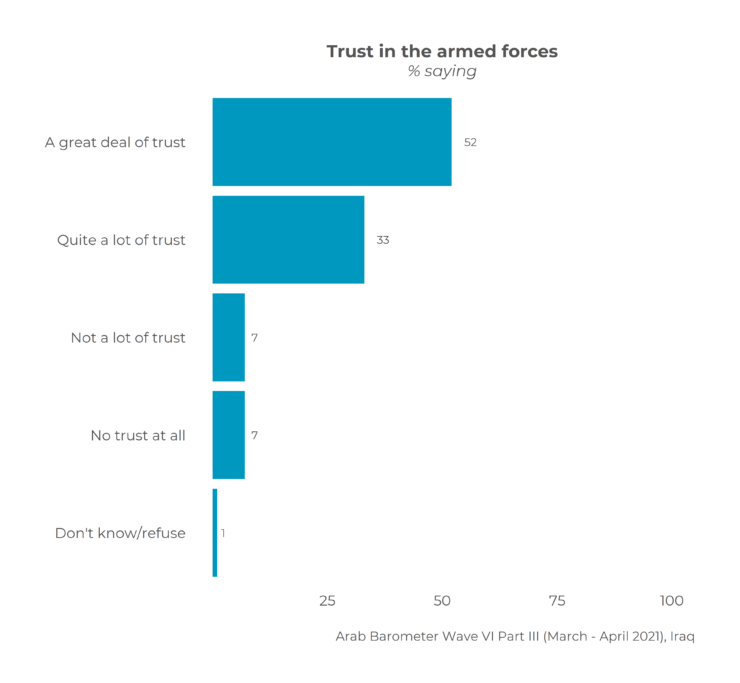

As for trust in the armed forces, the Iraqi army was able to regain some of the trust it lost after its humiliating defeat at the hands of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in Mosul in the summer of 2014. The army includes popular figures who fought heroically against IS – such as the commander of the Iraqi Counter-Terrorism Service (ICTS), Lieutenant General Abdel-Wahab as-Saa’di. According to the AB survey, 85% of Iraqis say they have a great deal of trust or quite a lot of trust in their armed forces.

However, the army faces the challenge to integrate the Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF) militia. The official consolidation of the PMF under the formal security system from December 2017 has politicised the army. This perception was evident in fall 2019 when former Prime Minister al-Mahdi, arguably pressured by the PMF, stripped off Lieutenant General Abdel-Wahab as-Saa’di of his power as the commander of the ICTS and assigned him to an administrative position at the Ministry of Defence. As-Saa’di saw the move as a humiliation to his military rank and feat of arms, and reportedly stated that he would rather go to jail than accept the decision. Mahdi’s decision was allegedly the trigger that sparked the protests of October 2019.

In May 2020, Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi reappointed as-Saa’di as the commander of the ICTS, but the growing influence of the PMF inside the army might eventually decrease the public trust of the army.

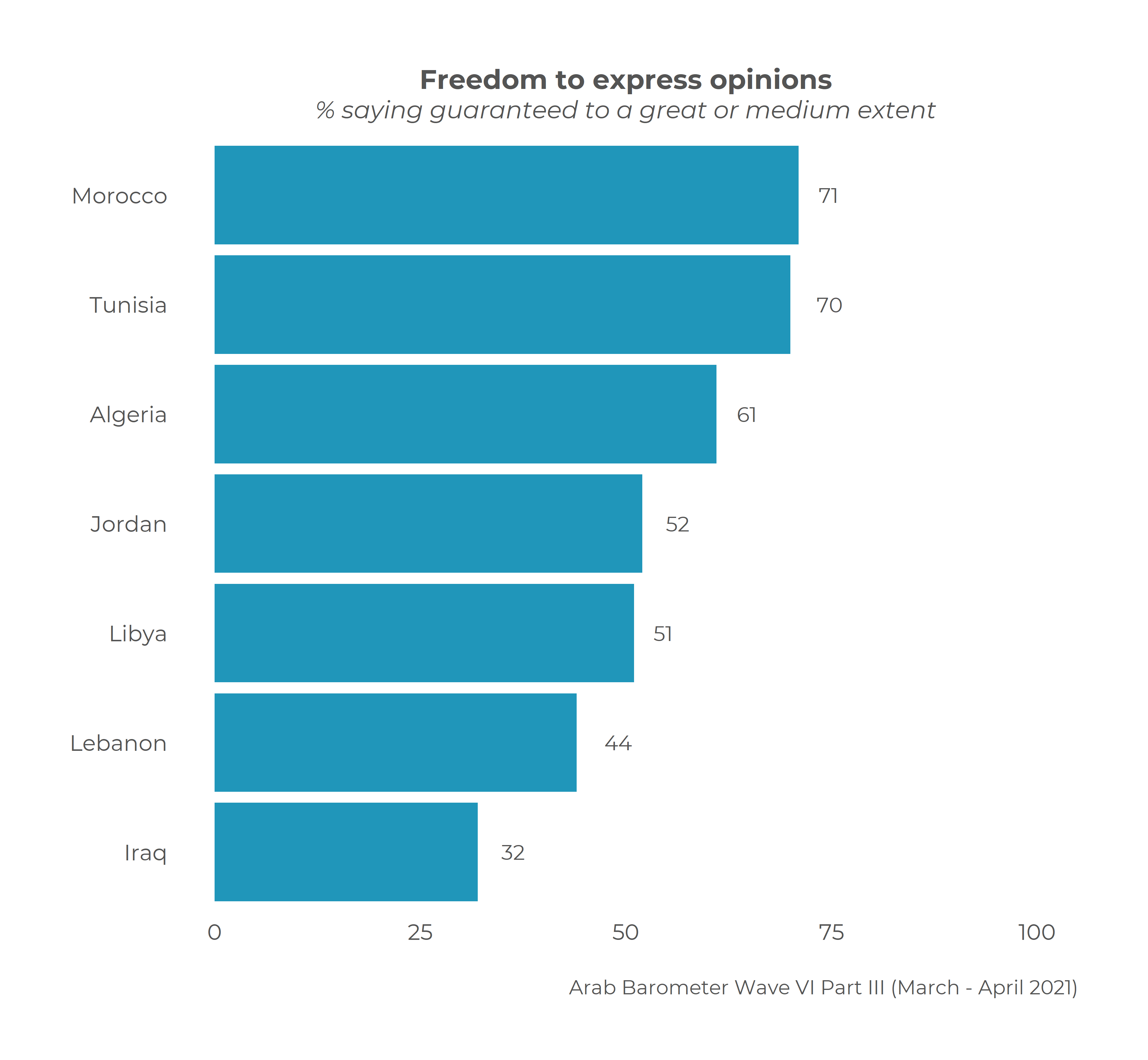

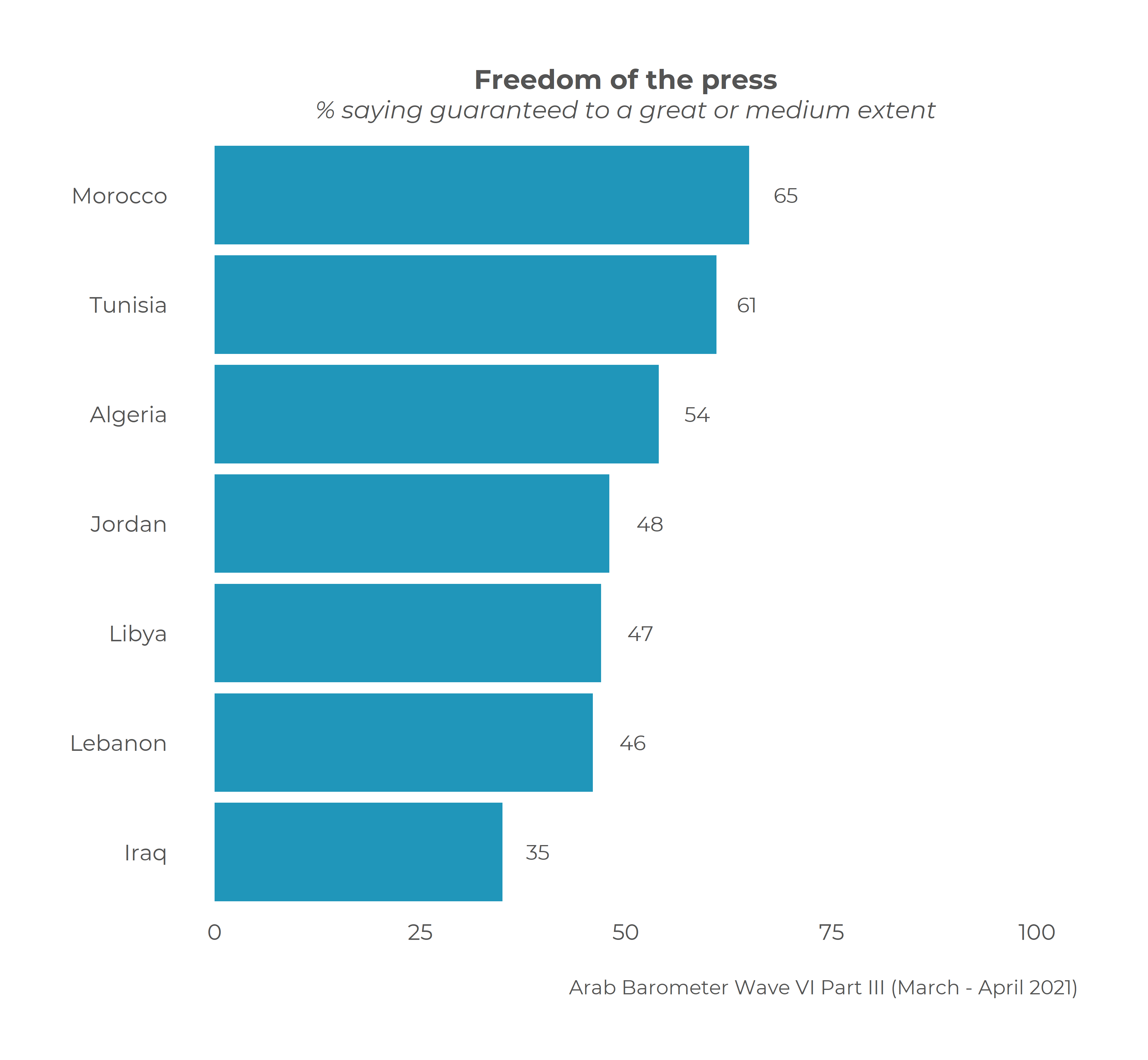

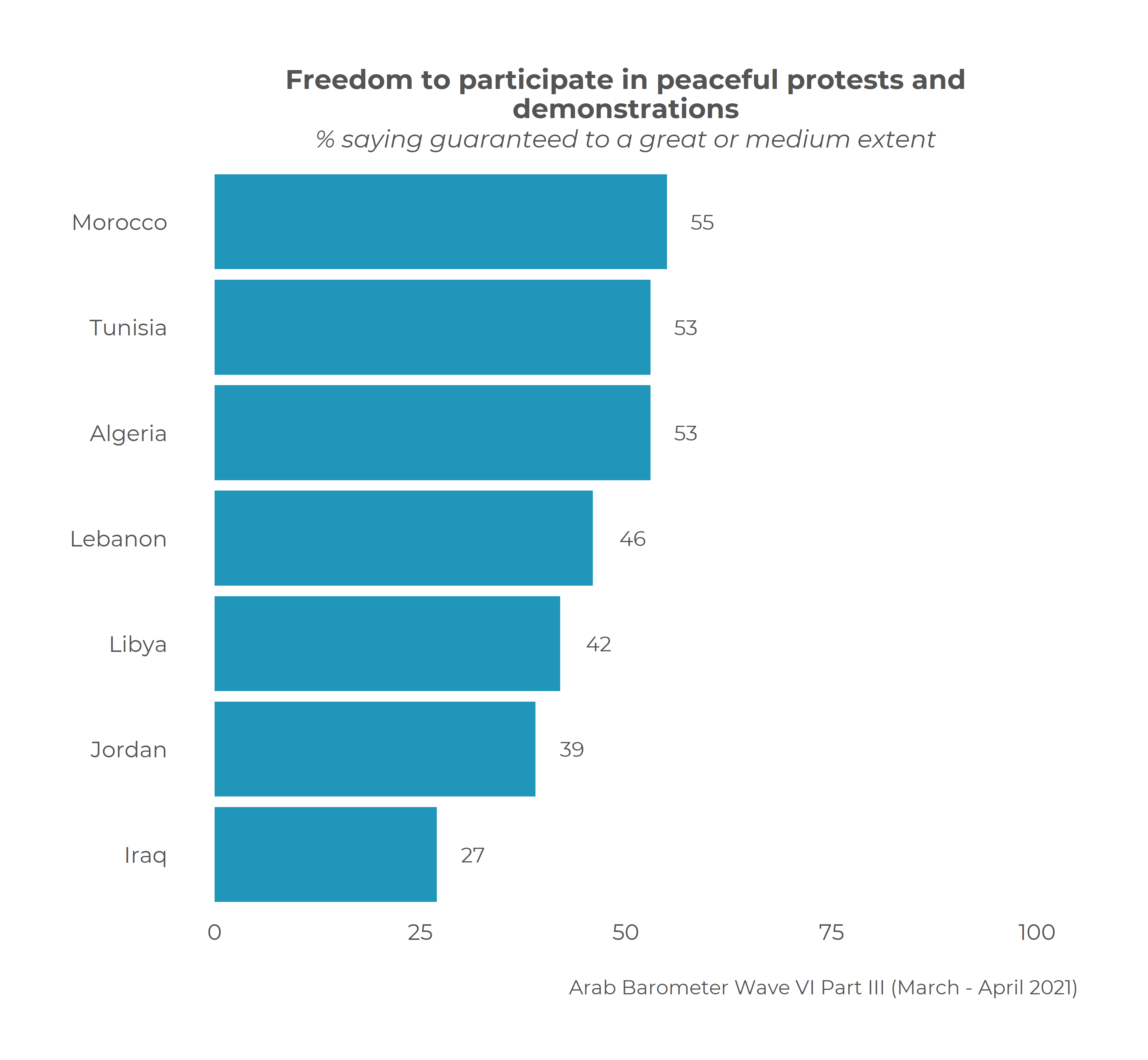

Civil liberties in Iraq are routinely abused. For instance, suspected IS members are denied fair trials, and there is evidence of torture in Iraqi jails. The policing measures against the October 2019 protests caused about 500 deaths and over 7,000 injuries. This infringement perhaps explains why as few as 27% of people say that the freedom to participate in peaceful protests is guaranteed, the lowest percentage among the countries included in the AB survey. In addition, the authorities have jailed 3,000 demonstrators. Militias are frequently harassing LGBTQ+ people. Only a third of Iraqis say that freedom of expression (32%) and freedom of the press (35%) are guaranteed, which are the lowest among all countries included in the survey.

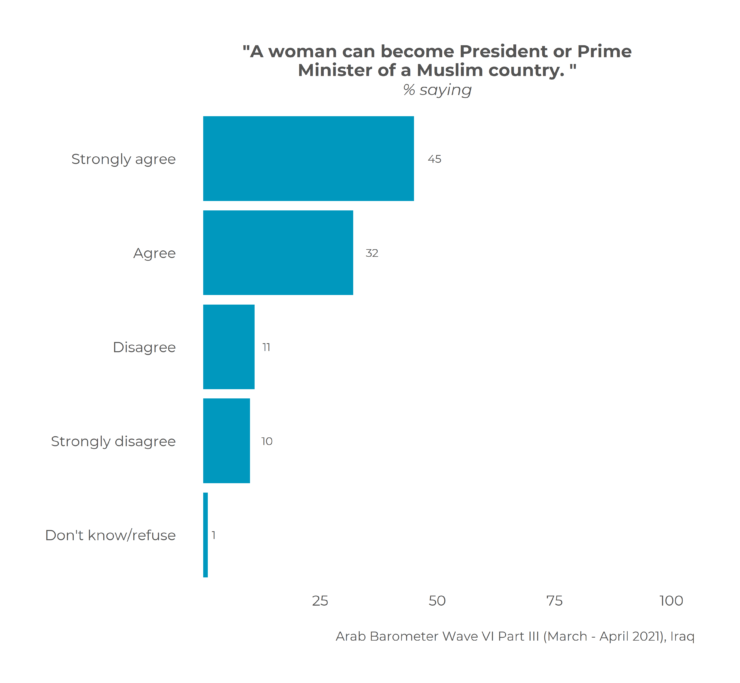

Women’s rights are regularly violated. For instance, domestic violence cases increased in numbers during the Covid-19 pandemic (UN women 2020). In addition, women experience discrimination in the labor market. On the one hand, they lack means of transportation to access the job market. On the other, priority for employment is often given to men, while women are expected to take care of the household. This issue is especially challenging in rural areas. That said, most Iraqis (77%) do not object to women becoming presidents or prime ministers of the country. Moreover, the majority agree that university education is crucial across gender.

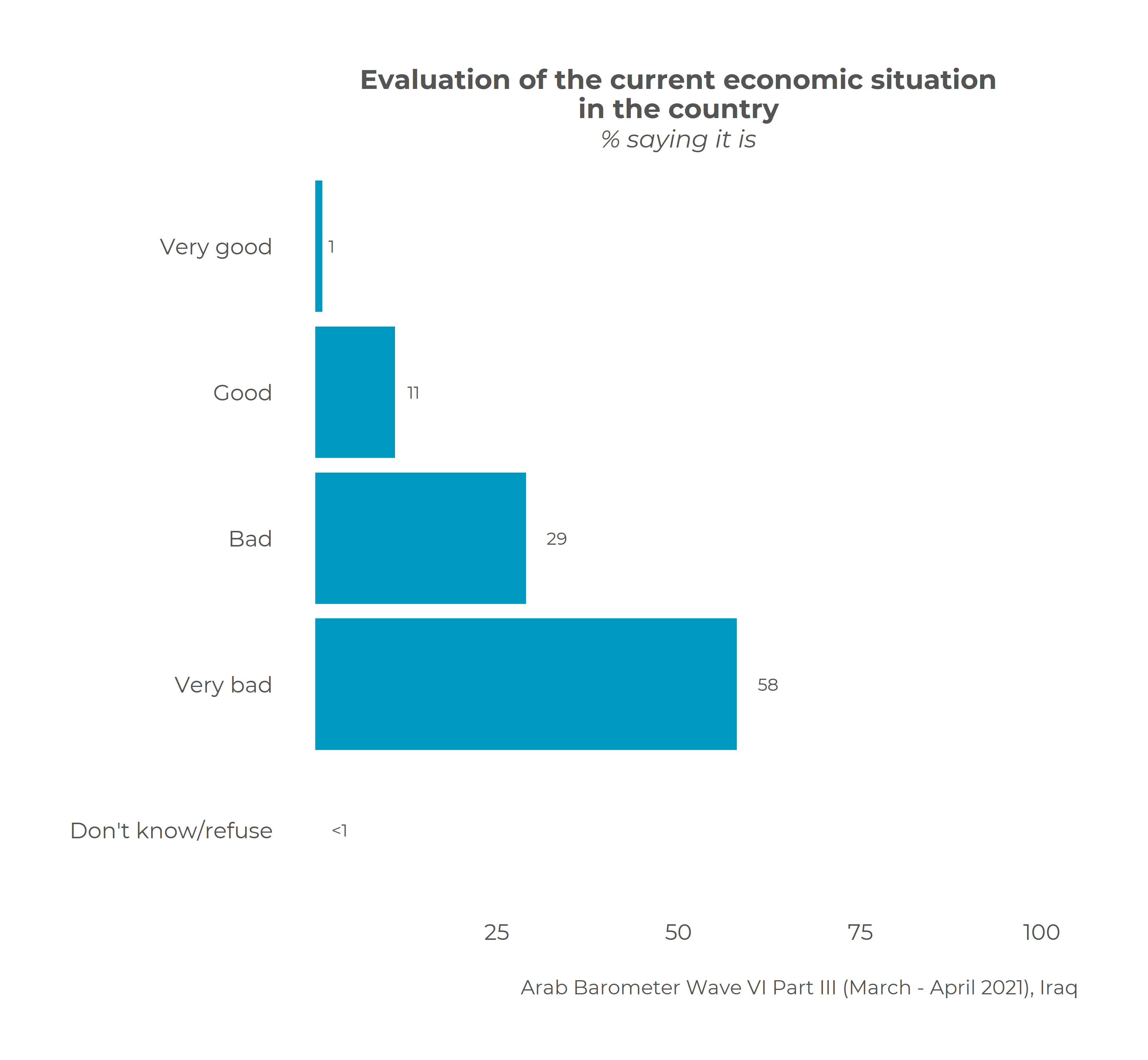

Iraq’s economy remains heavily dependent on oil. The drop in oil prices in 2020 caused a decrease in Iraq’s GDP. While Iraq embraces the market economy, political instability, corruption, and the Iraqi investment law have hindered the establishment of the private sector. Hence, public dissatisfaction over the economic performance of the FG is high, especially given that al-Kadhimi’s government is not able to control corruption and smuggling activities across the borders with Iran and Syria. Only 12% of Iraqis evaluate the current economic situation as very good or good

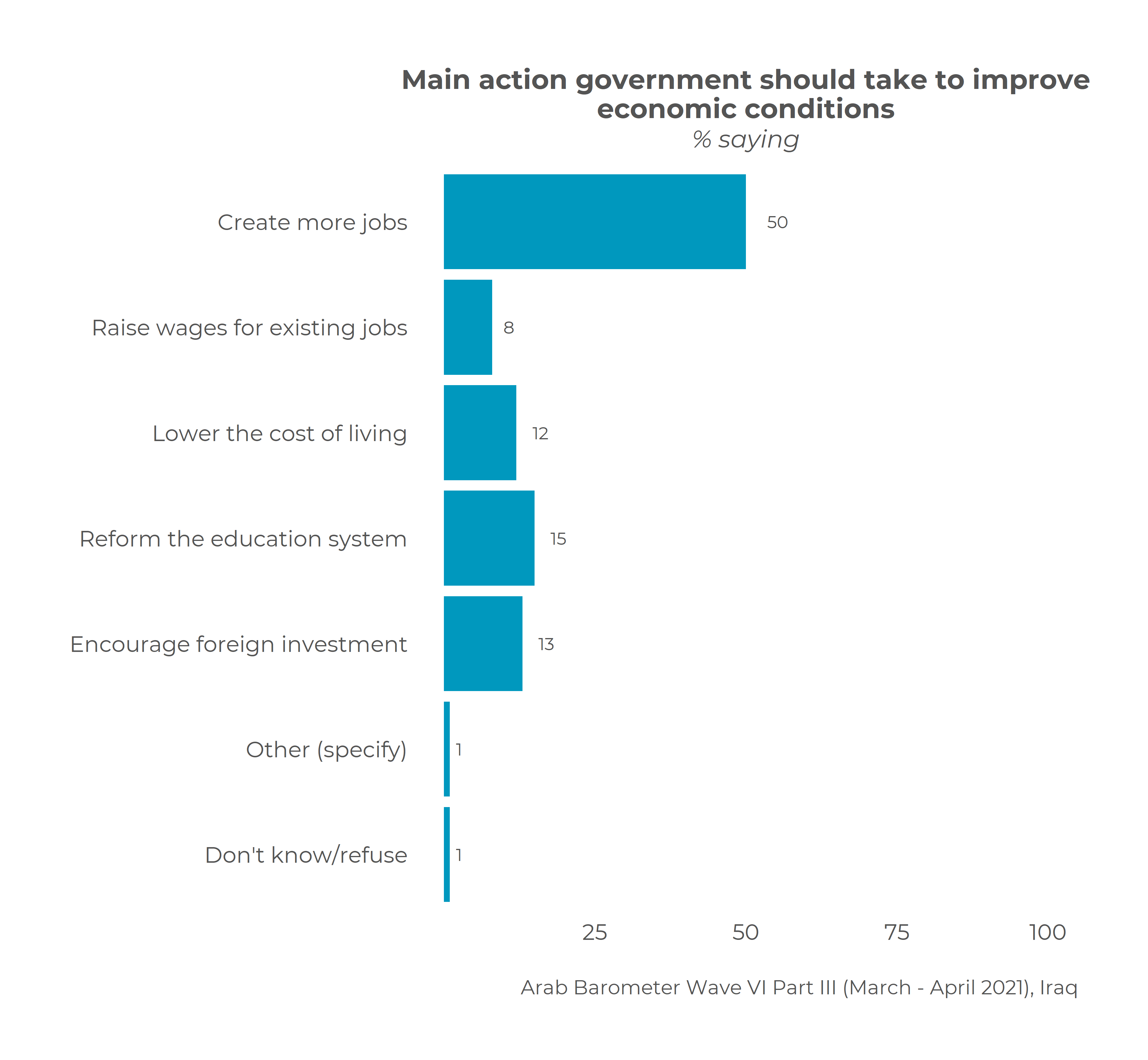

With the decline of oil prices, poverty rose further during the Covid-19 pandemic, especially among internally displaced persons (IDPs). In addition, international reports show that more than 4 million individuals in Iraq are in need of humanitarian assistance. Moreover, unemployment rates have increased from 8% in 2012 to nearly 14% in 2020. When asked about the most important issue the government should be focusing on to improve economic conditions, Iraqis often point to the need to create more job opportunities (50%).

The country confirmed its first case of Covid-19 in March 2020. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Iraq had 2,313,370 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 25,105 deaths between 3 January 2020 and 15 March 2022. A total of 17,014,009 vaccination doses has been delivered as of March 2022.

Like anywhere else, the pandemic had a major impact in the poor and rural areas. Public’s dissatisfaction with the FG reached new heights because of the mishandling of the Covid-19 outbreak. As mentioned above, only 6% of Iraqis say the government is doing a very good or a good job in responding to the COVID-19 outbreak. While it was able to impose a broad lockdown, the government could not provide resources to track, test, and treat Covid-19 cases. Moreover, hospitals were swamped, with limited medical oxygen supplies and prices of hygiene products and masks soaring. The government was unable to secure alternative sources of income for those who lost their businesses or jobs due to confinement measures, nor was it able to secure relief aid to the public in general.

The pandemic weakened KRG’s Syrian refugee policy. And due to unresolved budget concerns with the FG and the economic constraints created by the pandemic, the KRG reduced the pay of many civil servants by around 20%, which caused unrest and protests in 2020.

Dr. Amjed Rasheed is a Hillary Clinton fellow at Queen’s University Belfast. The views expressed in this piece are his own.