Chinese leaders have often boasted about their country’s “miracle” progress in alleviating poverty and indicated their willingness to share their expertise with other nations.

Take its “Belt and Road Initiative,” also known as the New Silk Road. China has spent nearly one trillion dollars in the last decade building highways, railways, ports and energy plants from east Asia to Europe in a bid to boost global trade.

But development experts who monitor such programs have long said that there’s a catch – that China burdens countries with unsustainable debt as it asks for repayment and that it leaves human rights abuses in its wake.

Maybe the critics are wrong?

Now a major new survey looks at how countries view their participation in China’s development projects. The finding challenges critics who say that countries have an overall negative experience. And of course … it’s a bit controversial.

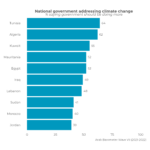

AidData, a research lab at William & Mary University, surveyed 7,000 leaders in public, private and civil society sectors in over 140 countries. They asked participants to score the progress of various goals such as economic stability, security, public services and employment.

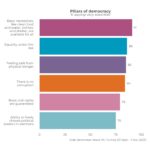

Lead report author Samantha Custer tells NPR that leaders with China as a development partner felt more optimistic across the board than countries that did not work with China. These China aid recipients were more likely to agree that their country had made progress on government accountability, physical security and social inclusion.

“Leaders often say they like that China is very quick to deliver financing and assistance,” Custer explains. “For newly elected leaders when they need to deliver promises quickly, China is a preferred partner [compared to Western ones] because there is not as much red tape.”

But does the survey ring true?

Others in the sector are skeptical of the participants’ ability to be candid.

John Calabrese, director of the Middle East-Asia Project at the Middle East Institute wonders if taking leaders’ answers at face value may give a misleading picture.

“I would guess at least some Middle East and North African [MENA] officials would not wish to air any problems or dissatisfaction with China lest this compromise their relationship,” he says.

Custer says that the participants were afforded various levels of anonymity, but she cannot exclude the possibility that some may have felt intimidated.

But she believes there may be other theories for the reports of optimism. Perhaps these countries may have a lower expectation for internal reform or may find that projects work well “despite, rather than because of, China’s contributions.”

Calabrese added that certain features of the Chinese model may appeal to the leaderships of some countries, such as non-interference in other country’s domestic affairs. A 2022 report by Arab Barometer – a non-partisan research network – revealed that China remains more popular across the MENA region than the United States.

Read full article at NPR