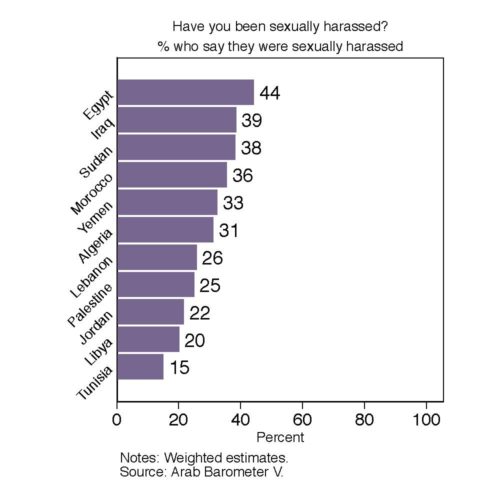

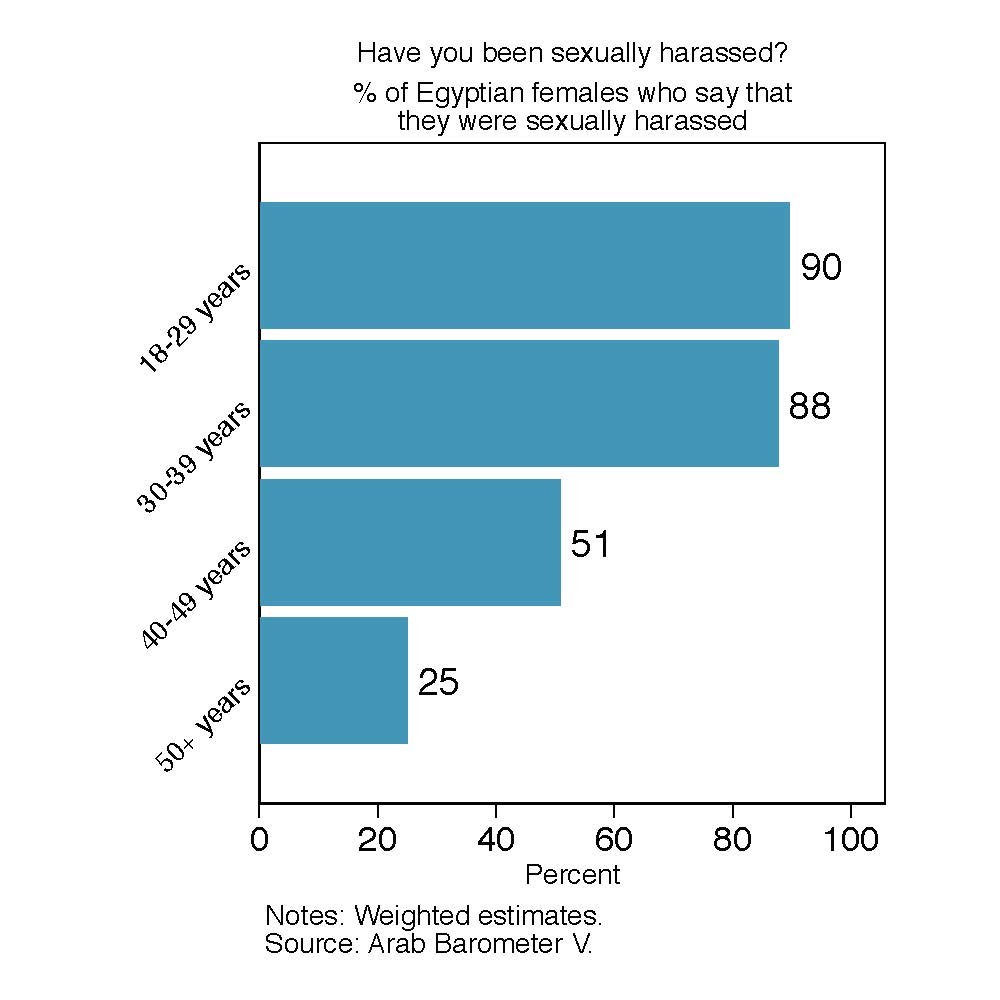

Sexual harassment (SH) is a serious problem in Egypt. In the Arab World, Egypt ranks first in SH: the Arab Barometer’s fifth wave finds that within a twelve month period, 42 percent reported some verbal harassment and 29 percent reported some physical harassment across genders. The problem is particularly acute for women, with 63 percent of women reporting some form of SH within a twelve month period – and almost all younger women reporting some form of harassment (90 percent of women aged 18-29, and 88 percent of women aged 30-39). Globally, in a Thomson Reuters survey of the world’s 19 largest megacities, Cairo ranked the most dangerous city for women overall and third most dangerous regarding sexual violence. A nationally representative survey found that nearly 40 percent of young women aged (13-35) reported SH in 2014, including 60 percent of those in informal urban areas (Ismail, Abdel-Tawab, and Sheira 2015). Finally, a governmental study reported that more than 1.7 million women experienced various forms of SH in public transportation, around 2.5 million experienced SH in streets within twelve months, and around 16,000 women aged 18 or more were exposed to SH at educational institutions within twelve months, costing the Egyptian state 571 million Egyptian pounds per annum. Given these figures, it is important to explore current policies for preventing SH against women and suggesting some possible solutions for the creation of safe public spaces for women in Egypt.

Globally, in a Thomson Reuters survey of the world’s 19 largest megacities, Cairo ranked the most dangerous city for women overall and third most dangerous regarding sexual violence. A nationally representative survey found that nearly 40 percent of young women aged (13-35) reported SH in 2014, including 60 percent of those in informal urban areas (Ismail, Abdel-Tawab, and Sheira 2015). Finally, a governmental study reported that more than 1.7 million women experienced various forms of SH in public transportation, around 2.5 million experienced SH in streets within twelve months, and around 16,000 women aged 18 or more were exposed to SH at educational institutions within twelve months, costing the Egyptian state 571 million Egyptian pounds per annum. Given these figures, it is important to explore current policies for preventing SH against women and suggesting some possible solutions for the creation of safe public spaces for women in Egypt.

In recent years, SH rose to public prominence specifically after an ugly episode of mass sexual assault by policemen in 2005 called “Black Wednesday.” Following the incident, many campaigns and initiatives were launched to fight against SH in Egypt. In 2006, the Egyptian Center for Women’s Rights (ECWR) issued their first campaign named “Safe streets for all,” followed by many youth initiatives such as “Respect Yourself” in 2007, “Be a Man” in 2009, “Syndicate the Harassers” in 2010 , OPANTISH 2011, and so on. Those efforts bore fruit after the Egyptian revolution in 2011. The Egyptian state recognized the problem and started to undertake measures to protect women from SH. This recognition appeared clearly in both the legislative and the institutional framework.

But current policies and initiatives merely include raising awareness and advocacy, legal support for victims, and self-defense training for women. While welcome, these initiatives focus on a single dimension of policy change, simultaneously ignoring other dimensions such as changing gender stereotypes and patriarchal norms. Such norms attribute harassment to immodest behavior and women’s dress, and provide justification for men who commit harassment. Thus, in my research, I have discovered that even though women are increasingly aware of themselves as victims of harassment, they are disincentivized from reporting harassment, even to their families. Recent survey data my colleagues and I have analyzed from the 2016 Survey of Young People in Egypt – Informal Greater Cairo (SYPE-IGC) confirms this: only 0.4 percent of those who experienced verbal harassment reported the incident to the police. None of the women who experienced non-verbal harassment reported it to the police. Moreover, only 36 percent of those who experienced verbal harassment in the previous six months told anyone about the experience (Hassan, Roushdy and Sieverding, forthcoming).

To prevent harassment, raising awareness and training provision is insufficient, and must be accompanied with creating safe reporting systems in police stations across all communities. Stationing female police officers is also critical in order for women to feel comfortable and safe reporting harassment. Additionally, sites of harassment such as school, youth centers, public transportation systems, and markets, need to make reporting of harassment more accessible.

Critically, and to supplement the provision of safe and secure formal reporting mechanisms, informal reporting must be incentivized through just and secure community-based resolution. This can be a much more powerful tool to combat harassment and change social and cultural norms pertaining to victim blaming and stigmatizing women who experience harassment. There is an abundance of research showing that women may feel shame, embarrassment or fear of not being believed if they were to report experiencing harassment. Some feel that their community and their own families would blame them for having experienced harassment, which could damage their reputations, or impose restrictions on their mobility (Hassan et al., ibid). Working with the community leaders and stakeholders is of profound importance for changing the culture of stigma and encouraging women to report harassment.

References:

Ismail, S., Abdel-Tawab, N., Sheira, L., 2015. Health of Egyptian youth in 2014: Knowledge, attitudes and behaviors, in: Roushdy, R., Sieverding, M. (Eds.), Panel Survey of Young People in Egypt 2014: Generating Evidence for Policy, Programs and Research. Population Council, Cairo, Egypt.

Hassan, R., Roushdy, R., Sieverding, M., forthcoming, An application of the ecological model to understanding and preventing sexual harassment in informal areas of Cairo. Population Council, Cairo, Egypt.

Rasha Hassan is a research consultant and a PhD candidate at Cairo University, Egypt.