A New Survey Shows the Promises and Perils Facing the Country’s New Government

A year after the fall of President Bashar al-Assad, Syria remains a country very much in transition. Much of its infrastructure is in tatters, and the price tag for rebuilding the war-torn state stands at over $200 billion. It is in desperate need of laws and institutions that can facilitate reconstruction, hold war criminals to account, and ensure that the new government is responsive to its citizens. The country, in other words, must remake itself at a time when it is struggling to function.

To figure out how Syria can best rebuild, its leaders and international supporters must understand the wants and needs of the country’s citizens. And so from October 29 to November 17, Arab Barometer—a nonprofit research network that we help direct—conducted its first ever survey of Syria’s people. Together with a local partner, RMTeam International, we gathered 29 interviewers and had them speak with 1,229 randomly selected adults in person, in each participant’s place of residence. The surveyors spoke in both Arabic and in Kurdish.

Our results provide reasons to be optimistic about Syria’s future. We found that the country’s people are hopeful, supportive of democracy, and open to foreign assistance—including from the United States and Europe. They approve of and trust their current government. But our results also provide reasons for concern. For starters, Syrians are broadly unhappy with the state of the economy and with public services. They are worried about internal security. They want to right past wrongs—those that happened both before and after the fall of the Assad regime—yet they disagree about which ethnic and religious group’s suffering is most deserving of attention. Finally, the government’s popularity varies wildly by region. Ahmed al-Shara, the country’s new president, is liked overall. But he and his team suffer from low ratings in some governorates dominated by the country’s minorities.

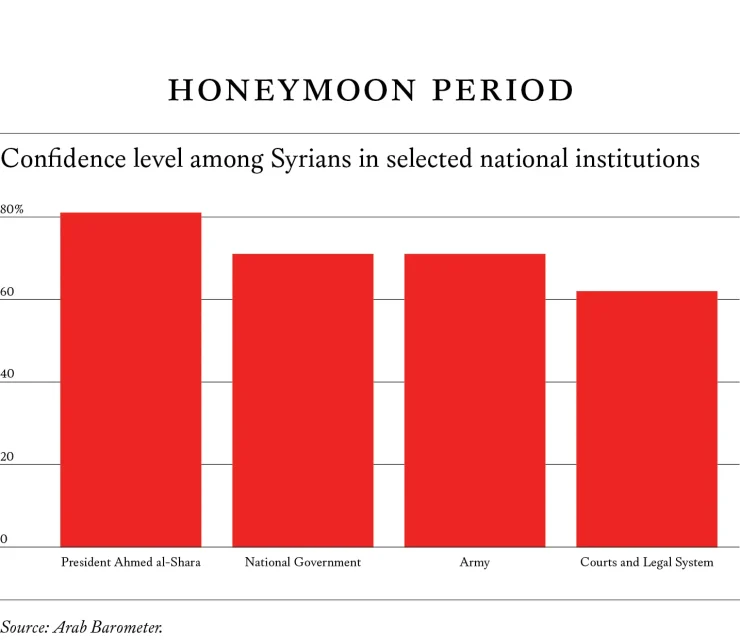

Damascus thus has a tough task ahead. The new government has bought itself time to transform the country for the better, thanks to its favorable ratings. But eventually, the honeymoon will end, and the government will be judged by its own performance. If Shara and his team cannot make Syrians more prosperous in the near future and engage all of the country’s citizens, their ratings might plummet, and Syria’s internal strife could come back with a vengeance.

GOOD NEWS, BAD NEWS

In politics, perceptions can change quickly. But for now, Syria’s new government has approval ratings that should make other world leaders envious. According to our survey, 81 percent of Syrians are confident in Shara. Seventy-one percent are confident in the national government as a whole. Sixty-two percent are confident in the courts and the legal system, and 71 percent support the army.

These positive responses do not appear to simply be the result of political repression. Many of the government’s critics were not shy in their remarks with our interviewers. Yet healthy majorities of Syrians agree that they have freedom of speech (73 percent), freedom of the press (73 percent), and the freedom to participate in peaceful protests (65 percent). A smaller number—53 percent—are confident that the newly elected People’s Council, the country’s unicameral parliament, will represent their interests. Just 40 percent believe that the government explained the election process for parliamentarians clearly and gave everyone an equal opportunity to compete. But nonetheless, 67 percent of Syrians agree that the government is very responsive or largely responsive to what people want.

It isn’t hard to see why Syrians are enthusiastic. The country’s current leadership has been in power for just over a year, and people are comparing its nascent record to Assad’s lengthy, brutal tenure. Seventy-eight percent of Syrians report experiencing one or more life-upending challenges between 2011 and 2024, such as displacement, the confiscation or destruction of property, the disruption of livelihoods or education, the deaths of family members, or political intimidation or harassment. In comparison, just 14 percent report experiencing one or more of the same challenges since the start of 2025. Fifty percent of citizens believe that corruption currently plagues national state agencies and institutions, but 70 percent see it as less widespread than it was under Assad. Seventy-six percent believe their children’s lives will be better than their own. It thus follows that 76 percent of Syrians think that Shara’s policies will be better for Syria than those of his predecessor.

But eventually, memories of Assad will fade, and Syrians will begin to evaluate Shara by how they feel contemporaneously. And when they do, Syria’s new government may find itself in trouble. Syrians most commonly cite the economy as their main political concern, and just 17 percent are happy with its performance. Inflation (31 percent), a lack of jobs (24 percent), and poverty (23 percent) were cited as the most serious challenges facing the country, when citizens were given a menu of choices. On an individual level, 56 percent of Syrians report that securing their basic needs is difficult. A staggering 86 percent suggest that their net household income does not cover their expenses, and 77 percent of citizens are dissatisfied with the efforts of governing authorities—although this is not always the national government—in generating employment. Food insecurity affects an alarming share of citizens, with 65 percent of all Syrians and 73 percent of self-described internally displaced persons reporting that in the last 30 days, they often or sometimes ran out of food before having the money to buy more. Likewise, most Syrians are deeply unhappy with the state of public infrastructure. Fewer than half of all Syrians are satisfied with the provision of electricity (41 percent) and water (32 percent), the availability of affordable housing (35 percent), and the health-care system (36 percent).

Finally, Syrians remain worried about their security. Although almost all Syrians—94 percent—report feeling safe in their own neighborhoods, they list the need to secure a monopoly over the use of force as the second-biggest challenge facing the country. Most Syrians believe that collecting weapons from all armed, nonstate groups (74 percent) and unauthorized individuals (78 percent) are critical threats that they want the government to address. Kidnapping is seen as a critical threat by 63 percent of citizens…

Read full article at Foreign Affairs